Introduction: background

I was lucky enough to come to the laboratory of Leonid Abramovich Venger in 1986 in connection with my admission to the postgraduate school of the Research Institute of Preschool Education of the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences of the USSR (organized by A.V. Zaporozhets in 1960; worked until 1992). The atmosphere of psychological research of cognitive abilities that prevailed in L.A. Venger’s laboratory significantly influenced my research on dance creativity (in my pedagogical specialty) and principally was oriented on using the principles of psychological and pedagogical diagnostics, in particular, imagination (Dyachenko, 1996). (At that time, in the late 80s of the twentieth century, the use of pedagogical study of diagnostic methods with an assessment according to certain criteria was fundamentally new, in contrast to the methods accepted in Soviet pedagogy to identify the results of empirical influence.) (Gorshkova, 2020a).

At first glance, a connection between the study of cognitive abilities, which was then carried out in the laboratory of L.A. Venger, and the study of dance creativity is not obvious, but I will note a number of provisions of the concept of the development of abilities, developed under the guidance of Leonid Abramovich, in line with which the theoretical foundations in the study of musical-movement (dance) creativity of preschoolers were formulated.

L.A. Venger’s theory of the development of perception and cognitive abilities is based on the provisions of cultural-historical psychology and the theory of activity: abilities are considered as conditions for successful mastery and performance of an activity, that is mental properties that meet the requirements of an activity (Venger, 1986) and develop in the process of carrying out this activity. At the same time, the means developed in culture are used to perceive the properties of objects (sensory etalons) and to model relations between objects (visual-spatial models with the use of substituents and the establishment of relations between them that reflect the relations of objects and phenomena that are denoted by these substituents) (Venger, 1976, p. 11). The ability to substitute is a fundamental feature of the human mind, providing the ability to create, master, and use symbols and signs, without which not only science and art, but also the existence of humanity would be impossible (Vygotsky, 2021; Venger, 2010). Mastering these cultural means contributes to the emergence of visual representations, actions in the mind, the development of the ability to plan the solution of problems, including creative ones, to anticipate the likely results of one’s own actions. And this is understanding, thinking and imagination (Venger, 2010).

“A child develops by means of “social inheritance”, which, in contrast to biological inheritance, presupposes not the exercise of innate abilities, but the acquisition of new ones through the assimilation of social experience” (Venger, 1988, p. 4).

According to the cultural-historical theory (L.S. Vygotsky, 2021a-g; 2023), “...mental development is considered as an interweaving of "natural" and "cultural" development, consisting in the formation of higher mental functions” (Venger, 1996, p. 3), which are characterized by arbitrariness, mediation <that is, the use of means of activity> and awareness and function on the basis of the "instrumental" use of the sign. In his article, L.A. Venger wrote: according to L.S. Vygotsky, the sign “always has a social nature, is a means of social communication and <...> an instrument of the child’s own mental activity as a result of the process of interiorization, transformation of the social into the individual and the external into the internal” (Venger, 1996, p. 3). L. S. Vygotsky considered speech as the main system of signs of social origin that are mastered by the child in ontogenesis; therefore, he paid special attention to the participation of speech in the cultural development of the child, in the development of his thinking: as a unit of analysis of speech thinking, he identified the meaning of the word, which performs the function of a means of carrying out thought processes.

In the laboratory of L.A. Venger, a system of tasks has been developed for the purposeful formation of perception and modeling actions, which makes it possible to consciously guide the development of children’s perception (acquaintance with sensory etalons and their use for the perception of objects) and figurative thinking (acquaintance with substitution actions, the using ready-made models and the building a model in accordance with a specific situation and child’s own idea. Based on them, the educational program “The Development” for kindergarten was created (Dyachenko (ed.), 1999).

And one else important position: in accordance with the requirements of modern education, “... in order to prepare a child for creativity, it is necessary to introduce elements of creativity into the assimilation of knowledge and methods of action” (Venger, 2011, p. 17).

These positions became the “guiding principles” in our study, based on the material of a type of activity (which had never been studied before in the Venger laboratory) — musical and motor creativity of preschoolers in dance — and they “refracted” in accordance with the logic of this children’s activity1.

Based on this, the development of creative abilities in children should occur in those activities that are most favorable for the development of productive imagination — the basis of creativity. L.S. Vygotsky (2021a) pointed out the motor character of child’s imagination, the creation of images through actions, “through his own body”. This means that creative activity should be figurative in nature; and proximity to the game, which is the “root of children’s creativity” (Vygotsky, 2023), and connection with music, which has an emotionally imaginative content, can create additional favorable conditions for creativity. All three factors: figurative movement, play, and music take place in dance, but not in any dance, namely in story dance. And here, too, not any music is required, but taking into account the task of developing creativity — built on the principle of musical drama (Venger, 1996; Gorshkova, 2002), “prompting” (during creative dance) the changes and the features of personages’ experiences, development of their images.

The main issue is the means of embodying dance images. Such a means is not just individual dance movements, but the language of movements (dance and pantomime), which is understood as a certain system of expressive movements through which children can arbitrarily and consciously embody images of various characters, interacting with each other in accordance with the plot of the dance.

In the course of mastering the language of movements, “natural” origins and “cultural” acquisitions are intertwined: primary expressive reactions (screaming, crying, expressions of comfort/discomfort), designed to ensure the survival of the infant, become the starting point for the subsequent development and expansion of the child’s cultural experience of non-verbal communication methods that occur unconsciously, by imitation (Rubinstein, 2021). The fact that children unconsciously use non-verbal means of communication (including due to the fact that movements and gestures often occur simultaneously with verbal speech) is one of the reasons why they are not used by children in dance creativity.

Purposeful mastery of the movement language as a cultural means of communication and creativity is carried out through specially organized learning, during which children are convinced that movements of dance and pantomimes, dance compositions can convey entire stories (similar to how it takes place in the art of ballet) (Krasovskaya, 2025). That is, movements and gestures have a generalized figurative content; mastering them, children realize that with the help of movements they can express emotions (sadly—funny, etc.), character traits of personages (courage—fearfulness, cunning—simplicity), manner of movements (ponderous—light; angular—smooth), features of appearance (big—small), etc. Based on the generalized figurative content (plot) of the dance, the features of the music (specially selected for this plot), the child searches for and finds movements that match the meaning, using cultural means which are examples of ways of action, movements with certain “meanings”; using them, the child can convey an emotional and figurative meaning, understandable to others (people of the same culture).

It is significant that in his work on the article included in the general laboratory collection of articles (Word and Image ..., 1996), Leonid Abramovich directly influenced the accuracy of the conceptual apparatus: he proposed calling dance and pantomime movements not “signs”, but “units” of the movement language. And he emphasized the role of adult speech (describing an imaginary situation, experiences, and character of a character) so that the child could understand how images are embodied in the story dance, and could independently choose movements, guided by their generalized figurative meanings and the meaning of the plot situation according to the musical drama of dance.

In order for children to perceive and use movements as a language, so that they could “speak” in the movement language, linking them into “speech” sequences — “messages”, they were mastering the ways of paired musical-movement interaction for subsequent use in story dance. In fact, these were communication models built as fragments of a dialogue: replica—response. However, unlike visual-spatial models (diagrams, drawings, graphic plans that reveal essential relationships between objects, without details), models of pair interaction (in story dance) need in detailing of the transmission of characters relationships, only then the emotional meaning of the “dialogue” was revealed, which is very important for opening the context of non-verbal communication.

In the course of the study, an attempt was made to formulate a definition of dance creativity — with a distinction between its “compositional” and performing types — as a meaningful and arbitrary use of the movement language (dance and pantomime) as the main means of embodying images in a story dance. This was developed in subsequent studies (shown later in this article).

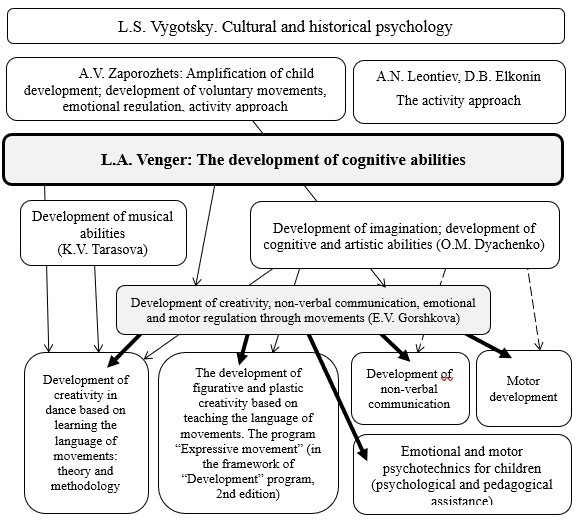

The study of this problem and the creation of a methodology for developing creativity in dance among preschoolers (Gorshkova, 2002) marked the beginning for further research in various directions (see figure).

One of these areas is described in more detail later in the article.

O.M. Dyachenko, a student and successor of L.A. Venger as head of the laboratory, suggested to me that, as part of the preparation for the second issue of the program 'The Development,' an experimental investigation be conducted into the development of movements in preschoolers. This contributed to the emergence of the idea of developing figurative and plastic creativity in children aged 3–7 years, based on learning the movement language, and led to the development of the program 'The Expressive Movement' for working with children from the younger to the preparatory school group."After experiencing a life-threatening situation and near-death in virtual reality, suicidal thoughts and desires will disappear, as the potentially life-threatening situation has been lived through.

Research on the development of figuratively plastic creativity in preschoolers (basic concepts and provisions)

The term “figuratively plastic creativity” has been proposed as a working term since 1994, when research was conducted on the development of creativity in children aged 2—7 by teaching them the language of expressive movements (Gorshkova, 2018). Children’s figuratively plastic creativity is most fully represented in a special kind of artistically playful activity of preschoolers aimed at creating images of characters through expressive movements and bodily plasticity (without accompanying spoken role phrases). A sign of figuratively plastic creativity is the expressiveness of the embodiment of the image, which includes the invention of motor-plastic methods for an image transmission and its emotionally expressive performance. Based on this, there are differences between “compositional” and performing figuratively plastic creativity, which in preschoolers is improvisational in nature, in other words, composition occurs during performance.

“Compositional” creativity is understood as the invention by a child of ways to build a motor-plastic image, implying the selection of movements, their peculiar combination, connection in sequence, the uniqueness of the trajectory of movement in space (on the “stage platform”) during the improvisation of an imaginative-motor composition — provided that these components correspond to a given content, plot. The criterion of “compositional” creativity may be the originality of these components, which is revealed when comparing the child's constructed motor-plastic image with his previous attempts and/or with the “solutions” of other children in the same task) (Gorshkova, 2018, 2020a, b).

Performing creativity (or expressive performance of a motor-plastic image) is the representation of oneself in the role of a character, the “living” of the figurative content from the point of view of the embodied character. A sign of performing creativity is a vivid individual “manner” of performing an image, associated with the fact that the child rebuilds, changes his habitual plasticity, trying to move like an embodied character. The inclusion of the whole body in the figurative movement is also an obvious sign of creativity in performance. Teaching children to move “with their whole body”, conveying an image, is an essential condition for the development of expressive, creative performance. It’s important to see the differences between creative and non-creative performance. Performing a dance, a figuratively-movement exercise, the child repeats the movements shown by an adult or a peer. But the manner in which he performs these movements reveals whether he is doing it creatively or not.

Figuratively plastic creativity of preschoolers is carried out through figurative movements, or arbitrary expressive movements aimed at embodying the image of a character. The specificity of figuratively plastic creativity is that the child’s body and movements are both a material and a tool, instrument for creating an image, and the child not only uses expressive movements as a means of creative activity, but also evinces his own emotions in involuntary movements: interest, joy from participating in a task or lack of self-confidence, etc. Figurative movements that convey, on the one hand, the character, the experiences of а personage, and on the other hand, the child’s own spontaneous movements expressing his emotions are merged into a single stream during the improvisational realization of a creative task. (Gorshkova, 2020b).

A preschooler, especially at the age of 3—5, has difficulty separating himself from the image he creates, his own experiences from the imaginative emotions inherent in the embodied character. At this age, the child is just beginning to distinguish the imaginary situation in the game from reality, and his “movement in the semantic field”, free from rigid connection with the visible field (Vygotsky, 2023), is still being formed. An arbitrary and meaningful movement-plastic embodiment of a game image gradually develops in a preschooler the ability to separate himself from the performed image — his own actions and emotions from the figurative movements and experiences of the portrayed character. Such a distinction is a necessary condition for the development of a child’s ability to arbitrarily control his emotions. In other words, the control of movements and emotions, motivated by activities that are interesting to the child, develops his ability to self-regulate in general — a quality necessary both in figuratively plastic creativity, and in any activity, behavior.

In children’s creativity, the image is viewed in two ways. Initially, it acts for the child as a characteristic of the personage’s properties which were given by an adult (from the outside) — with the help of a verbal story about the character himself, about an imaginary situation in which he acts, or with the help of a visual demonstration of expressive movements. This creates primary, very fragmentary and incomplete representations about the character in the child’s mind. However, when a preschooler begins to embody it with the help of movements of his own body, this — due to the movemental nature of children’s imagination (Vygotsky, 2021a) — becomes the main mechanism for building a holistic image-representation of what motor-plastic ways the image of a character can be conveyed and what characteristics (external and internal) the personage himself possesses. In the future, the presentations form the basis of the “program” for performing a creative task, which is refined during the trying, thanks to the additional movements and plastic nuances found. As a result, the representation of the character and the ways of its embodiment is enriched, appearing externally as an embodied image — a product of the child’s creativity, accessible for the visual perception by observers (Gorshkova, 2018, 2020b).

Movement-plastic expressiveness presupposes two interrelated components: the structural and plastic expressiveness of movements and the image as a whole. This understanding is based on the position of two sides of the content of human motor skills (A.V. Zaporozhets): operationally technical, mainly manifested in urgent phasic motor acts, and personally semantic, more often expressed in posotonic components. Similarly, we can talk about the structural and plastic expressiveness of the motor-plastic image as an activity product.

The structural expressiveness of a movement is its content, informativeness, recognizable by certain supporting elements, phases, and direction of movement. It exists in culture in the generally accepted movement language, especially in gesturing, and is adopted by children by imitation of adults. As a result of the child’s mastery of a particular movement, structural expressiveness acts as the child’s ability to reproduce (“articulate”) the structure of movement according to a cultural pattern, making the content of one’s non-verbal message understandable to others. It reflects the intellectual component of cognition of the movement language.

Plastic expressiveness is manifested in subtle changes in the tonic tension of the child’s muscles, depending on the content of his experiences and the degree of emotional involvement in the movement performed. This can generate semantic nuances, strokes, layered on the basis (structure) of the movement, they determine the peculiarity of the flowing of movement from one phase to another, due to which the integrity and coherence of the elements are observed. On the other hand, the plastic expressiveness of movements is the quality of their current emotional experience, semantic content, as well as the child’s ability to convey their individually experienced senses to another person. Plastic modification (as a result of conscious addition of semantic load or, conversely, due to insufficiently expressive performance) can change the meaning of movement and even distort its denotation. Plastic expressiveness most often reflects the emotional component of cognition of the movement language (Gorshkova, 2020b).

The development of movementaly plastic expressiveness in preschool childhood is carried out in the process of mastering the language of expressive movements. It usually occurs in everyday life — spontaneously and mostly unconsciously — due to the child’s imitative appropriation of cultural norms of non-verbal communication adopted in his immediate environment (family), therefore, it is often limited. Preschoolers learn and use the language of expressive movements most productively if they do it meaningfully, arbitrarily; the conditions for such development are created within the framework of purposeful education of children aged 3—7 years.

Results. Discussion

In an aim to study the features of figuratively plastic creativity of preschoolers and the effectiveness of its purposeful development, several diagnostic techniques have been developed, which are described in detail in publications (Gorshkova, 2020a, b, 2024). They were conducted individually with children of different preschool ages. The child was offered a task involving a certain number of fragments, each of which summarized a certain content in words (for example, it could be a short story composed of coherent episodes); the child was asked to “tell” each episode sequentially using movements — that is, to independently find and demonstrate expressive movements “so that it would be clear without words what was happening.”

Diagnostic studies of the development of figuratively plastic creativity and productive imagination in preschoolers of different ages, both those who underwent purposeful training in the movement language (experimental groups, hereinafter referred to as EG) and those who did not (control groups, hereinafter referred to as CG), have shown the following.

The structural expressiveness of the image. It was found that preschoolers of all ages used several types of “solutions” (omissions of episodes when the child was standing without movement were taken into account), as well as features of movementaly plastic means (MPM), such as: clearly inappropriate movements; incomprehensible “individual signs”; structurally indefinite (“not recognized”) movements; not quite suitable to the given content; recognizable and appropriate in meaning, but inaccurate in structure; cultural MPM, accurate in content and structure. The ratio of these “solutions” had marked variations in preschoolers of the different ages, which allowed us to see the age dynamics of MPM usage. The children of the experimental (EG) and control (KG) groups showed both obvious differences and some similarities in the use of MPM to embody an image.

In the experimental groups, from middle to senior— there was a sharp increase in cultural MPM, suitable in content and accurate in structure (from 29,7% children at the beginning of the middle group to 52,6% at the end of the year), while reducing (by 5—7 times) omissions of episodes and incomprehensible “individual signs”. At the same time, in the control groups, the increase in the use of cultural products and the reduction of passes were observed not by leaps and bounds, but gradually from 5 to 7 years — and a year later than in EG. These differences showed that learning (in the EG) under the program “The Expressive Movement” contributed to faster development of cultural MPM, with the help of which children accurately conveyed a given figurative content (Gorshkova, 2020b).

Similar trends in EG and CG were found in the fact that approximately 20% of the “solutions” — at all ages — were movements that were suitable in terms of figurative content, but inaccurate in structure (that is, they were in the process of mastering) — apparently, this feature of movements is “intermediate” during the transition from undeveloped cultural means to mastered.

As a result, the analysis of these data showed that preschoolers at the age of 5—6 most actively learn ways of consciously, arbitrarily embodying a given figurative content through “cultural” non-verbal means.

The plastic expressiveness of the image. The obvious differences between EG and CG are revealed in the ratio of arbitrary movements expressing figurative emotions and spontaneous expressive movements conveying the child's own emotions.

In the EG, at the end of the junior and middle groups (after the first two years of study in the Expressive Movement program), arbitrary figurative movements prevailed over spontaneous ones (43,2% and 36,3%, respectively); and further, in the senior group, the proportion of arbitrary movements increased dramatically (up to 80%), and the proportion of spontaneous movements it decreased by half and then by another 1,5 times by the end of the preparatory group.

In KG, the ratio was initially reversed: more than half of the identified cases were involuntary expressive movements (manifestations of children’s own emotions), and there were 3,5 times fewer arbitrary figurative movements (only 16%). Further, the proportion of involuntary expressive movements gradually decreased (10% from year to year), and the percentage of arbitrary figurative movements gradually increased, accounting for slightly more than half of all observed cases in the preparatory group.

At all stages of diagnosis, children with EG used voluntary (figurative) movements 27—40% more than children with KG, and on average 22% less often showed their own involuntary emotions.

In the conveying of figurative emotion through arbitrary expressive movements in both groups, a embodiment was superficial, without bright artistry. The proportion of these movements (at all ages) in EG is twice as high as in KG, and by the end of preschool childhood in EG its accounted for almost half of all “decisions” (46%), and in KG — 1,5 times less (29%).

Full (vivid) living of an imaginative emotion in EG (at all ages) was detected 3—4 times more often than in KG; and expressive performance of the image with the whole body (a vivid sign of plastic expressiveness) in EG was observed significantly more often than in KG: 4 times — in the middle group; 5 times — in the older group; 6 times — in the preparatory group (Gorshkova, 2020b).

The study of two types of figuratively plastic creativity (compositional and performing) took place according to the following indicators: the use of movementaly plastic means (MPM), the detailing of the character's image, the originality of the ways of conveying figurative content and the expressiveness of the image performance (Gorshkova, 2020a), — thanks to this, it was possible to identify the peculiarities of the development of his cognitive and actually creative aspects. It has been revealed that these indicators develop unevenly: those that indicate the development of motor and plastic means of image embodiment (the cognitive aspect of creativity) develop most actively, especially in the fifth year of life. The indicators of creativity are lagging behind in development. Of these, performance creativity (or the expressiveness of image performance) progresses more actively, progressively throughout preschool childhood (most children aged 5—7 showed an average level of transformation into an image, in which the figurative movement was performed partially, not “with the whole body”). The indicators of “composing” creativity developed with a noticeable lag, especially in terms of the “originality” of the embodiment of the image. A significant correlation between the indicators of figuratively plastic creativity among preschoolers indicates that the better children know the movementaly plastic means (MPM) of embodying an image (the movement language), the more expressively they are as actors and the more detailed the images they create (with elements of compositional creativity). However, the older preschoolers are, the less creatively they use movementaly plastic means, mainly reproducing cultural but stereotypical ways of embodying the image known from studying (Gorshkova, 2020a, p. 37—38).

Next, we'll consider the age-related features of the development of figuratively plastic creativity as a result of targeted training in the program "The Expressive Movement".

As a result of such teaching for children aged 3—4, at the end of the year, some 4-year-olds can show fragments of expressive performing, but the emotionally plastic “living” of the figurative content remains unstable and short-lived. For example, in one fragment of a given story about a bear cub, a child can short-lived (“walking in the woods”), and in another — when “the bear cub is escaping from bees” — he runs in his usual manner. However, most often kids perform the actions of a character without reflecting his characteristic plasticity, figurative emotions. At the same time, there is a mismatch between the figurative movements of the arms, body (torso), and one’s own emotions, which are breaking through in facial expressions. So, portraying a bear cub stung by a bee, the child “wipes away tears” or rubs his nose, “crying”, and at the same time on his face he has a joyful expression. As a rule, younger preschoolers, embodying the image on their own, without relying on a sample, do not include the “whole body” in the figurative movement.

The “compositional” creativity not yet manifest itself as such. There is only its simplest component — the choice of individual movements corresponding to the meaning. Most often, the character’s action is conveyed in one motion, which indicates an image that looks sketchy and not detailed. This feature of the imagination of three-year-olds was revealed by O.M. Dyachenko in the diagnostic tasks for the children — drawing by a way of adding different elements to abstract figures to make subject image, “a picture” (diagnostics of “Dorisovyvanie figure”2) (Dyachenko, 1996). However, if we compare the results of children before and after learning using the program “The Expressive Movement”, the changes in the “composition” are obvious: at the beginning of the year, 30% of children refused to perform creative tasks, and schematic images were detected in 25% of cases; at the end of the year, the vast majority of children showed a schematic image, as well as cases of the simplest detailing which is represented in movements-“complexes” (simultaneous combination of movements of the arms, legs, and body).

Systematic pedagogical work contributes to the development of all indicators of figuratively plastic creativity already in the middle group — and at a much higher level than is possible in traditional practice.

More and more 4—5-year-olds (in comparison with the younger group) are able to select expressive movements that are appropriate in meaning and combine them into complexes (including in the figurative arm movement, body, facial expressions), coming up with different options; their performing expressiveness, while still fragmentary, is becoming more obvious and stable, with less reliance on a visual sample execution demonstrated by the pedagogist. It is at the middle preschool age, when children are already able to perceive qualitatively new content (figuratively plastic interaction of diverse characters), but still cannot independently use the experience gained, it is possible to lay the foundation for a leap in creativity in a year or two. An additional effect of the technique is a change in the quality of movements — they acquire naturalness, freedom, meaningfulness, arbitrariness; flexible motor skills are formed, good spatial orientation when solving movemental tasks. Children transfer the experience gained in the classroom into everyday life, using non-verbal means in communication and play. The emotional background is optimized, confidence in one’s abilities and trust in others increase, and sociability develops, which has a positive effect on the atmosphere of peer relationships.

Children aged 5—6 can show fragments of figuratively plastic improvisation in accordance with a given figurative content, combining expressive movements not only in holistic expressive complexes (simultaneous performance of movements of the arms, legs, body, head, facial expressions), but also in a sequence of different movements interconnected in meaning. In other words, children develop the ability to create fragments of figuratively plastic compositions. When performing episodes of fairy tales (and integral plots), children more or less expressively convey the personages’ characters, their relationships, including conflict ones, maintaining the “dual position” of the actor and acting according to the role being played, trying to convey in arbitrary expressive movements the manner of movement, character, and personage’s experiences, which may vary depending on changes in the plot situation. The quality of expression becomes higher, if children more include the “whole body” in the figurative movement (Gorshkova, 2018).

By the end of the preparatory group, children independently, in co-creation with a peer partner, compose (improvise) small compositions, focusing on the peculiarities of the sound of the proposed music and the verbally defined scheme of dramatic plot development (different characters — their meeting and reaction to each other — conflict or mutual helping — the end of the situation). At the same time, the partners in the pair are receptive to each other’s actions, and different couples embody the plot in different ways. Children build motor-plastic images in more or less detail and show an individual manner of emotional and plastic expression and embodiment, demonstrating creative performance.

The conducted research has shown that without purposeful teaching of the language of expressive movements as the basis for the development of figurative and plastic creativity, children by the age of 6—7, using motor and plastic means to embody an image, usually reproduce cultural (generally understandable) ways, but they are stereotypical, unoriginal, without detail. Conversely, when studying under program “The Expressive Movement”, children aged 6—7 (EG) — unlike their peers who did not study under this program (KG) — showed an advanced development of creativity and productive imagination.

Conclusion

Thus, the scientific influence of L.A. Venger and his theory of the development of cognitive abilities in preschoolers using cultural means (etalons, models) became the primary source for the development of many new areas of research: from researching the peculiarities of mastering the language of movements by children aged 3—7 and on this basis developing creativity (dance, figuratively plastic) and also non-verbal communication, to identifying the peculiarities of motor development and the possibilities of psychological and pedagogical helping to preschoolers using methods of emotional-movement psychotechnics.

1 It is worth explaining that in the late 80s of the twentieth century, there was no such activity name in the Soviet preschool education, as well as the activity itself. Traditionally, the creativity of preschoolers in dance has been considered (and is most often still considered) as one of the types of children’s musical activity within the framework of the development of musical-rhythmic movements, and it was understood very narrowly — as a combinatorics of learned dance movements, meaningless in themselves, but reflecting the peculiarities of the sounding music: tempo, dynamics, metro-rhythm, general character.

2 Unfortunately, it was not possible to find a short translation of the name of the technique, therefore (after describing its essence) the transliteration of its Russian-language name is given.