Introduction

Digital transformations and the emergence of increasingly “smart,” personalized digital tools, such as smartphones, the Internet of Things, and artificial intelligence technologies, constituting a technosystem as a key component of the modern human development ecosystem, define the formation of a 21st-century anthropological type, the technologically extended personality (Soldatova, Voiskunsky, 2021). Within the framework of a socio-cognitive concept of digital socialization, grounded in L.S. Vygotsky’s cultural-historical approach, digital environments and devices are regarded as cultural tools mediating mental functions, social interaction, new forms of activity, and the cultural practices of the individual. The technosystem, as part of the external environment, expands the capacities of both children and adults, integrating into their cognitive, behavioral, and social systems, modifying and extending them. Human development within such an ecosystem represents a natural stage of social evolution and calls for a conceptual focus on the integrity of the technologically extended personality (Soldatova, Ilyukhina, 2025), as well as the development of specialized instruments for its study.

The universal principle of integrity is reflected in various psychological frameworks (Kostromina, Grishina, 2024). It is embodied in L.S. Vygotsky’s key ideas on the unity of higher mental functions, sensory and motor processes, the integration of affect and intellect, the sign as a “determining whole,” and the meaningful whole of “object-tool-sign” activity (Vygotsky, 1984). Integrity is also considered a methodological lens for analyzing individuality as an anthropological principle (B.G. Ananyev, A.G. Asmolov, S.L. Rubinstein, K.A. Abulkhanova, A.V. Brushlinsky, V.S. Merlin, V.D. Nebylitsyn, et al.). The concept of integrity has been addressed in various international psychological schools (G. Allport, A. Maslow, C. Jung, C. Rogers, E. Erikson). In practice-oriented approaches, integrity is viewed as a hypothetical end point of human and personal development, which individuals strive toward but can never fully attain. A changing world presents constant challenges to integrity, and the ontological fragmentation, complexity and multidimensionality of life at the intersection of the real and digital necessitate the construction of a new form of integrity, more complex and inclusive of the digital dimension (Soldatova, Ilyukhina, 2025).

The need to consider integrity as a fundamental principle of human self-regulation in the process of adaptation to rapid change becomes increasingly evident. Previously, we developed the Digital Daily Life Self-Management Scale (DDLSM), which includes indicators such as experience of digital daily life, engagement in digital sociality, and digital device management (Soldatova et al., 2024a). Given the conceptual independence of each of these indicators, the addition of a new parameter, integrity, will allow a more comprehensive analysis of the technologically extended personality and the examination of potential personality profiles according to different combinations of these parameters. We will focus on the key criteria of integrity in the context of continuous extension of the self through technological tools during digital socialization.

Within the cultural-historical psychology paradigm, the human body is regarded as the first object of mastery and transformation in ontogeny, becoming a universal tool and sign (Tkhostov, 2002). Building on L.S. Vygotsky’s ideas, the body can be conceptualized as a key meaningful boundary that provides the process of self-mastery with integrity and a specific structure (Smirnov, 2016). Drawing on psychodynamic approaches, neuropsychology, and attachment theory, the integration of the bodily and psychological self is understood as the basis for experiencing one’s psychophysical wholeness, continuity, and uniqueness (Krueger, 2013). Digital technologies influence the user’s physical condition, and excessive use is associated with physical discomfort, manifesting in disrupted sleep, irregular eating patterns, reduced physical activity, and other negative health outcomes (Kelley, Gruber, 2013; Kokka, 2021; Paakkari et al., 2021). In this context, bodily integrity can be measured by attention to one’s physical needs regardless of offline or online activity, whereas its disruption may be reflected in continuing digital activity despite experiencing physical discomfort.

Identity as an integrative personal construct is considered a key phenomenon for understanding the integrity of the technologically extended personality (Soldatova et al., 2024b). E. Erikson defines identity as the continuity and sameness of a person to themselves. Identity is dynamic, changing and developing throughout life, while simultaneously maintaining a certain temporal continuity that supports personal integrity (Erikson, 1996). The process of integrating and constructing a coherent, non-contradictory identity is viewed as one of the main trajectories of personal development, recognized by most researchers (Grishina, 2024). Empirical studies indicate a tendency for virtual and real identities to converge in mixed-reality contexts, leading to the emergence of hybrid identities (Kopteva et al., 2024; Soldatova et al., 2022; Zimmermann et al., 2023). Integrity of identity can be reflected in the effort to maintain an online self-image congruent with one’s actual state in real life, whereas its disruption may manifest as experiencing oneself as a different person in digital environments.

Digital devices act as new extensions that expand the boundaries of the self and, consequently, its integrity. In his description of the development of the proprium as a path to achieving integrity, G. Allport identifies a stage of self-boundary expansion, beginning around age four, when a child becomes aware of what is “mine” not only in relation to their body but also to elements of the surrounding world (mother, toys, cat, etc.) (Allport, 2002). In the extended mind framework, E. Clark and D. Chalmers demonstrate that cognitive processes can extend beyond the human brain to include external objects, such as smartphones. They propose several criteria for incorporating an object into the integrated perception of an extended mind: availability, functional support, reliability, and trust (Clark, Chalmers, 1998). Studies building on this perspective examine phenomena reflecting special experiences of closeness to digital objects as significant parts of the self, including emotional attachment expressed through attributing character and emotions to a device and caring for it (Park, Kaye, 2019), the need to customize a device to personal preferences, and anxiety experienced in its absence (Ross, Kushlev, 2025). Thus, the integrity of the technologically extended personality may be determined by the drive to personalize one’s device and incorporate it within the boundaries of the self, whereas the opposite pole is characterized by a lack of attachment, reflecting the perception of the device as alien or external.

Autonomy is recognized as one of the key characteristics of personality, supporting greater integration and effective self-regulation. In Russian psychology, autonomy is considered in the context of the development of personal independence (L.S. Vygotsky, D.B. Elkonin, S.L. Rubinstein, A.A. Bodalev). As a basic human need, autonomy occupies a central place in self-determination theory, manifesting as a sense of self-directedness, freedom of action, and the ability to achieve personal goals (Deci, Ryan, 2015). The specific nature of digital environments can create a perception of expanded opportunities for exercising autonomy, surpassing the limitations of the physical world. This may lead to an imbalance in one’s self-experience across real and virtual contexts. In this framework, an indicator of the integrity of the technologically extended personality may be the equal perception of the significance of achievements in both real and virtual life as a result of exercising autonomy. A disruption of integrity may be reflected in experiencing greater independence in the virtual world compared to the real world.

From the perspective of the cultural-historical approach, personality integrity is understood as the result of the mediation of the psyche by cultural tools, which ensure coherence of behavior and the internalization of social norms. Digital platforms, as a new type of psychological tool, can disrupt this unity. A striking phenomenon illustrating this disjunction is the online disinhibition effect (Suler, 2004). This effect reflects changes in the developmental social situation, where online interaction becomes a fragmented activity due to the specific characteristics of the digital environment, including anonymity, physical distance, the absence of familiar social cues, and lack of immediate emotional feedback. Significant differences in behavior between the virtual and real worlds may be considered a risk to the integrity of the technologically extended personality. Integrity can also be reflected in taking into account the expectations of significant others when enacting behavior in both real and virtual contexts.

The value-meaning domain is considered one of the key dimensions for understanding personality. D.A. Leontiev, for instance, identifies the meaning-making sphere as the principal constitutive substructure of personality. Personality can be understood as a “coherent system of meaning-based regulation of life activity,” encompassing the entire system of relationships with the world, including the temporal perspective as a whole (Leontiev, 2003). In the context of digitalization, this criterion of personality integrity is defined by the individual’s ability to ascribe meaning to their online activities based on a unity of motives, values, and life orientations within a mixed-reality environment. The opposite pole may manifest as the inability to adhere to one’s values and principles in the online space.

Self-knowledge in psychology is regarded as a crucial instrument for achieving personal integrity. Within the subject-centered approach to personality psychology (S.L. Rubinstein, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, A.V. Brushlinsky), one of the main criteria for defining a subject is the capacity for reflection and well-developed self-knowledge skills. Digital transformations create both new opportunities and new risks for self-knowledge. On one hand, practices such as self-tracking and lifelogging, recording all events on digital media, provide unprecedented opportunities for self-exploration (Lupton, 2016), allowing individuals to quantify themselves and their life experiences and access this data at any time. On the other hand, researchers highlight the “dark side” of self-tracking, namely its potential negative effects on psychological well-being and health, which remain poorly understood (Feng et al., 2021). These effects may manifest as an externalization of self-knowledge, where the focus shifts from internal self-perceptions and the development of personal capacities to external quantitative indicators (likes, steps, ratings), potentially representing a step toward the loss of personal agency and subjectivity.

Thus, the issue of integrity takes on a new perspective when the personality becomes technologically extended and supplemented by digital tools, presenting new challenges in finding strategies for integration to maintain well-being within a different cultural-historical context (Soldatova, Ilyukhina, 2025). Given the conceptual independence of each of the indicators, extending the Digital Daily Life Self-Management Scale through the addition of a new parameter, integrity, allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the technologically extended personality and the examination of potential personality profiles in terms of adaptation and well-being in a mixed-reality environment.

Objective. The objective of the study was to develop and validate an extended version of the Digital Daily Life Self-Management Scale (DDLSM-2), supplemented with a subscale measuring the integrity of the technologically extended personality (“Integrity of Personality”), and to identify personality profiles of the technologically extended individual based on all subscales.

In line with this objective, the following hypotheses were formulated:

-

The addition of the “Integrity of Personality” subscale will preserve the structure of the DDLSM, including the subscales Digital Device Management, Experience of Digital Daily Life, and Digital Sociality.

-

The “Integrity of Personality” subscale will be positively associated with measures of happiness, hardiness, and basic beliefs.

-

Combinations of scores across the four subscales will allow identification of several profiles of the technologically extended personality, differing in their potential for adaptation and well-being in a mixed-reality environment.

Materials and methods

Participants. The study sample included 1841 respondents, comprising 649 adolescents aged 14–17 (M = 16,3, SD = 0,7, 55% female) and 1192 young adults aged 18–39 (M = 23,4, SD = 6,1, 64,3% female). Participants resided in the cities of Moscow (32,2%), Saint Petersburg (14,9%), Tyumen (14,7%), Rostov-on-Don (19,2%) and Makhachkala (19,1%). The sample included school students (17,3%), college students (24,7%), university students (34%) and employed respondents (24%).

Development of the “Integrity of Personality” Subscale. The development of the subscale was guided by the criteria of integrity for technologically extended personalities identified in the theoretical section. Following expert review of multiple item formulations for each criterion, two items (one direct and one reverse-scored) were selected per criterion. These addressed bodily self (“I pay attention to my body and physical needs regardless of whether I am online or offline,” “I often continue digital activities even when I feel physical discomfort”), identity (“I change my avatars on social networks and messengers to match my current appearance,” “Online, I feel like a different person, unlike my real-life self”), expansion of self-boundaries (“Before using a new device, I fully customize it for myself,” “I am not attached to my smartphone and can easily replace it”), autonomy in mixed reality (“My achievements in real and virtual life are equally important to me,” “I feel more independent in the virtual world than in the real one”), consistency of social norms (“In my actions, both online and offline, I consider the expectations of people important to me,” “Online, I behave in ways I would not behave around acquaintances in real life”), value-sense orientations (“What I do on the Internet is meaningful; for me, it is also part of real life,” “Online, unlike in the real world, I do not always manage to follow my life values and principles”), and self-knowledge (“Through the Internet, various apps, and digital devices, I better understand my true self,” “Sometimes I rely more on likes, step counts, navigation apps, or information from the Internet than on my own sensations and experiences in the physical world”). Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

These items were incorporated into the DDLSM (Soldatova et al., 2024a), which comprised three subscales: Digital Device Management (conscious use and control of digital devices to ensure safety and efficiency), Experience of Digital Daily Life (reliance on digital devices in everyday life and emotional attachment to them), and Digital Sociality (engagement in digital social environments, including the importance of virtual self-presentation, feedback, and belonging to digital communities). The updated version of the instrument is designated DDLSM-2.

Measures. To assess the convergent validity of the “Integrity of Personality” subscale, the following instruments were used: the Maddi Hardiness Test (Osin, 2013), the Basic Beliefs Scale (Padun, Kotelnikova, 2007), and the Subjective Happiness Scale (Osin, Leontiev, 2020).

Data Collection. Data were collected through an online survey conducted from autumn 2024 to winter 2025 within a research network of universities, schools and colleges.

Data Processing. Data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 and Jamovi 2.4.8, employing CFA, Pearson correlation coefficients, ANOVA and cluster analysis.

Results

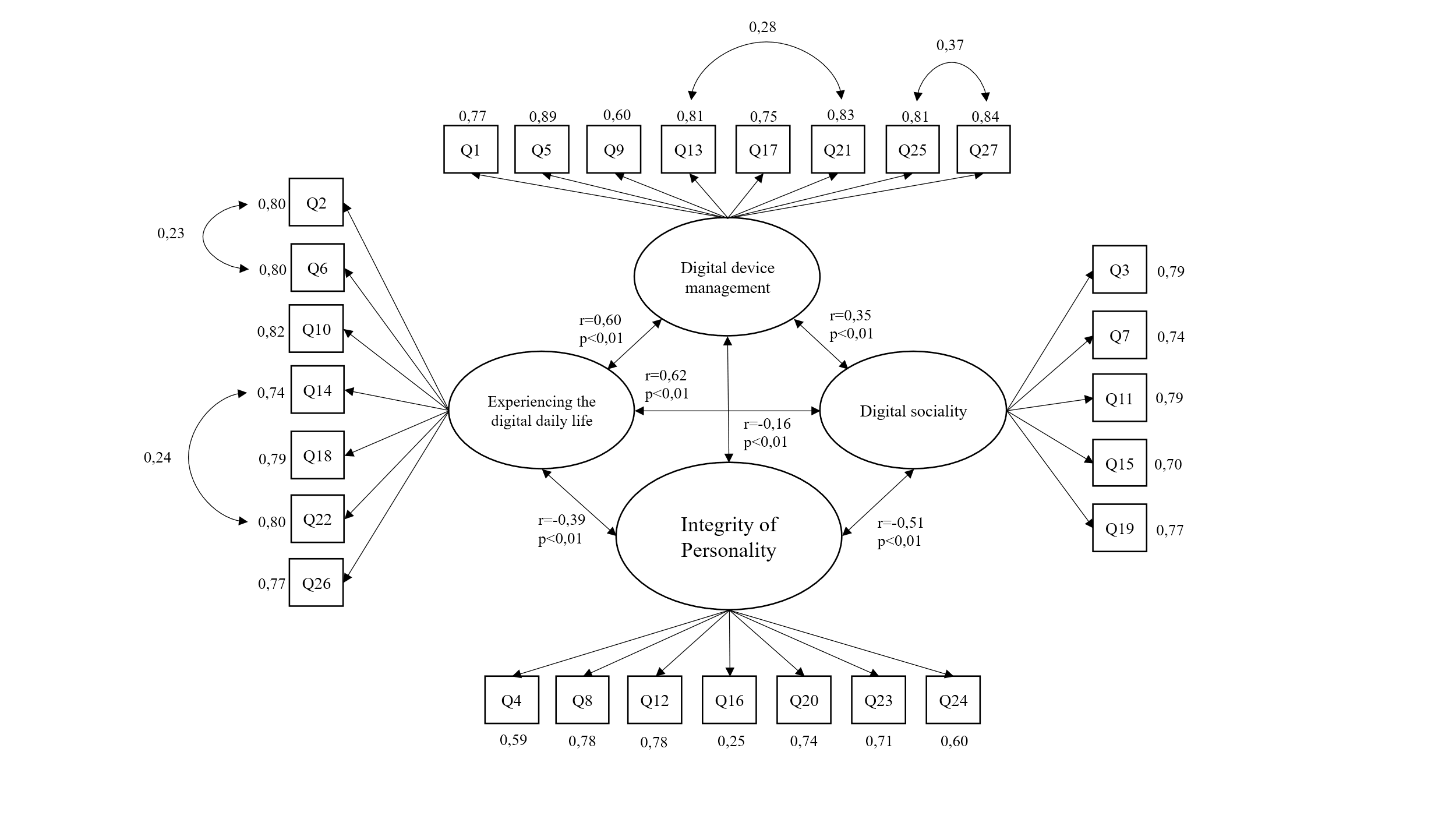

Factor Structure of the DDLSM-2 Scale. To evaluate the adequacy of the theoretical structure of the DDLSM-2, which comprises four subscales (“Digital Device Management,” “Experience of Digital Daily Life,” “Digital Sociality,” and “Integrity of Personality”), a CFA was conducted. The selected model included a seven-item “Personal Integrity” subscale (Cronbach’s α = 0,82, M = 3,6, SD = 0,9), with each item representing one criterion of integrity and formulated as a reverse-scored statement (Tables 1,2, Figure 1, Appendix A). Versions of the subscale that mixed direct and reverse-scored items, or consisted solely of direct items, did not demonstrate satisfactory internal consistency.

Table 1

Summary items of the subscale «Integrity of Personality»

|

№ |

Item |

М |

SD |

Cronbach's alpha if item deleted |

Correlation with the subscale |

|

4 |

I often continue my digital activities even when I feel physical discomfort (like hunger, back pain, or drowsiness) |

3,46 |

1,25 |

0,81 |

0,66** |

|

8 |

I feel like a different person online than I am in real life |

3,79 |

1,22 |

0,68 |

0,78** |

|

12 |

I feel more self-assured in the virtual world than I do in the real one |

3,68 |

1,27 |

0,67 |

0,77** |

|

16 |

I'm not particularly attached to my smartphone and could easily replace it |

3,02 |

1,30 |

0,84 |

0,46** |

|

20 |

I behave differently online than I would around people I know in real life |

3,72 |

1,24 |

0,78 |

0,77** |

|

23 |

It's harder for me to stick to my personal values online compared to offline |

3,73 |

1,19 |

0,78 |

0,76** |

|

24 |

Sometimes I prioritize online feedback (likes, step counts, internet information, GPS) over my own physical sensations and real-world experience |

3,51 |

1,31 |

0,80 |

0,69** |

Note: «**» — correlation is significant at the 0,01 level.

Following the post-hoc examination of potential ways to improve the fit of the scale structure to the observed data, several model modifications were introduced. Specifically, residual correlations were added between Items 13 and 21 (χ² = 154,8, residual factor loadings = 0,28, p < 0,01) and Items 25 and 27 (χ² = 250,9, residual factor loadings = 0,37, p < 0,01) within the “Digital Device Management” subscale, as well as between Items 2 and 6 (χ² = 96,7, residual factor loadings = 0,23, p < 0,01) and Items 14 and 22 (χ² = 102,5, residual factor loadings = 0,24, p < 0,01) within the “Experience of Digital Daily Life” subscale. All of these item pairs originate from the initial DDLSM subscales (Table 2, Appendix A).

Table 2

Quality indicators of the structure of the DDLSM-2

|

Sample |

Df |

CFI |

TLI |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

RMSEA 90% CI |

|

The entire sample (DDLSM-2) |

318 |

0,909 |

0,900 |

0,071 |

0,070 |

0,068–0,073 |

|

14—17 years old (DDLSM-2) |

321 |

0,919 |

0,911 |

0,064 |

0,069 |

0,065–0,073 |

|

18—39 years old (DDLSM-2) |

318 |

0,089 |

0,887 |

0,074 |

0,073 |

0,070–0,076 |

|

The entire sample (DDLSM-2) (post-hoc) |

314 |

0,925 |

0,916 |

0,071 |

0,064 |

0,062–0,067 |

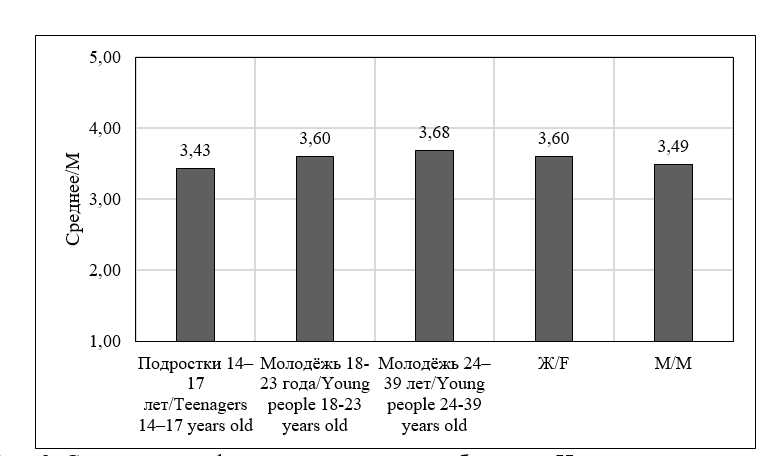

Sociodemographic indicators of the “Integrity of Personality”. Significant differences were found across age groups (F(2, 1838) = 11,2, η² = 0,012, p < 0,001) and between gender groups (F(1, 1833) = 4,0, η² = 0,004, p < 0,05). Scores on the subscale increased with age and were higher among females (Figure 2).

Validity of the “Integrity of Personality” subscale. The subscale shows significant associations with overall happiness, hardiness, as well as with core beliefs about the benevolence of the world, a positive self-image, belief in one’s own luck and a sense of personal control over one’s life (Table 4).

Table 4

Correlations of the indicators with the subscale «Integrity of Personality»

|

Scales and subscales |

Pearson correlation |

|

|

Happiness |

0,17** |

|

|

Hardiness |

Commitment |

0,28** |

|

Control |

0,21** |

|

|

Challenge |

0,23** |

|

|

Hardiness |

0,27** |

|

|

World assumptions scale |

Benevolence of World |

0,16** |

|

Justice |

0,07 |

|

|

Self-Worth |

0,19** |

|

|

Luckiness |

0,16* |

|

|

Control |

0,18* |

|

Note: «**» — correlation is significant at the 0,01 level.

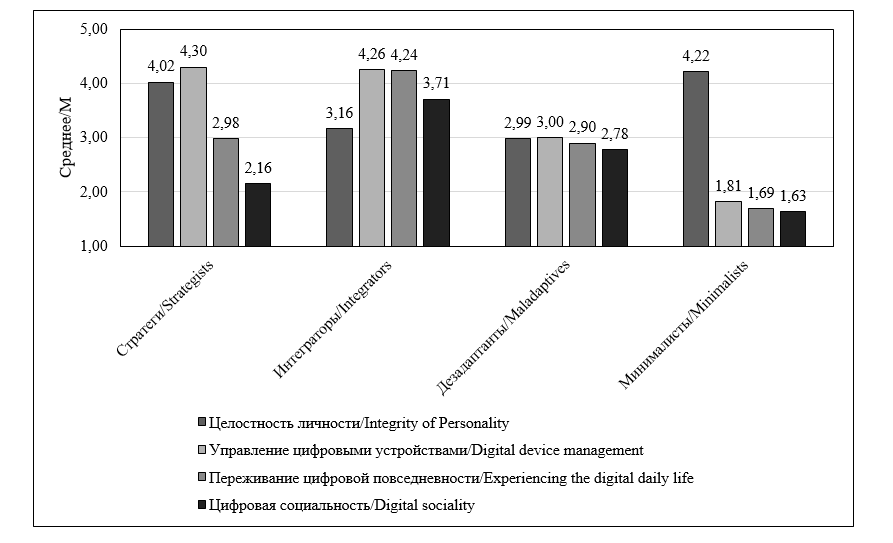

Personality profiles. Using hierarchical cluster analysis (complete-linkage method), four groups were identified that showed significant differences across all DDLSM-2 subscales: “Integrity of Personality” (F(3, 1837) = 282,7, η² = 0,32, p < 0,001), “Digital Device Management” (F(3, 1837) = 1767,9, η² = 0,74, p < 0,001), “Experience of Digital Daily Life” (F(3, 1837) = 1156,7, η² = 0,65, p < 0,001), and “Digital Sociality” (F(3, 1837) = 729,3, η² = 0,54, p < 0,001) (Figure 3).

One-third of respondents (31%) were classified into the first group, the “Strategists”; more than a third (40,4%) into the second, the “Integrators”; 14,3% into the third, the “Maladapters”; and 14,4% into the fourth group, the “Minimalists,” comprising roughly every seventh participant (Figure 3).

Differences among the groups were also found on the Happiness Scale (F(3, 1835) = 24,4, η² = 0,04, p < 0,01), with the highest scores observed in the first group, the “Strategists” (M = 19,2), and the second group, the “Integrators” (M = 18,0). Scores were lower in the third group, the “Maladapters” (M = 17,0), and the fourth group, the “Minimalists” (M = 16,6).

A partially similar pattern emerged for the Hardiness Scale (F(3, 1835) = 32,3, η² = 0,05, p < 0,01): the highest scores were found in the “Strategists” (M = 21,4) and “Integrators” (M = 18,3), with a decrease among the “Maladapters” (M = 17,9), but comparatively high scores in the “Minimalists” (M = 20,7).

Discussion of the results

Psychometric properties of the DDLSM-2. The obtained results demonstrate internal consistency, good structural quality, and factorial validity of the DDLSM-2, which includes four subscales: Digital Device Management, Experience of Digital Daily Life, Digital Sociality, and the newly introduced Integrity of Personality subscale. The relationships of the Integrity of Personality subscale with overall happiness, hardiness, positive self-concept, and belief in control over one’s life demonstrate its convergent validity. These findings are consistent with the widely recognized view of the importance of integrity for personal stability, development, and well-being (Kostromina, Grishina, 2024).

The negative association of the Integrity of Personality subscale with the other DDLSM-2 subscales indicates that at this stage of personal evolution, integrity is challenged in the context of digitalization across various spheres of life. In particular, high engagement in digital social life, the significance of digital extensions in everyday routines, and strong emotional attachment to them may complicate integrative processes. This aligns with existing research on the negative effects of social media and digital dependencies on personal well-being (Karakose et al., 2023; Sala et al., 2024). The seemingly paradoxical, although weak, negative correlation with the Digital Device Management subscale may be explained by the significant effort required for conscious regulation and control of digital devices. This effort likely depletes personal resources, which must be allocated both to managing digital extensions for effective functioning in mixed-reality environments and to maintaining personality integrity.

Integrity of the technologically extended personality. The new subscale includes only reverse-coded items reflecting risks to the integrity of the extended personality and its deficits, based on a set of symptoms of digital maladaptation. This finding is a significant substantive result, indicating that in the contemporary digital context, integrity is manifested problematically, through the identification of its violations. This aligns with the activity-based approach, in which development often occurs through awareness and resolution of contradictions and difficulties, highlighting zones of actual and near-term personal growth in interaction with technologies.

At the same time, the subscale items fully correspond to the original theoretical model, which includes seven criteria of integrity, confirming the complex and multi-level nature of this phenomenon. The results complement existing understandings of integrity by taking into account new digital realities and mixed-reality environments, emphasizing the importance of bodily self-integrity (Smirnov, 2016; Krueger, 2013), continuity and coherence of identity (Grishina, 2024), expansion of the boundaries of the self (Clark, Chalmers, 1998), value-semantic orientations (Leontiev, 2003), alignment with social norms of behavior (Suler, 2004), autonomy (Deci, Ryan, 2015), and self-knowledge (Feng et al., 2021).

In the integrity of the technologically extended personality, a key capacity is the ability to master digital tools while maintaining a balance between the real and the virtual, prioritizing the former, and using digital technologies functionally and instrumentally without losing connection to physical and social reality. Such a person demonstrates the ability to self-regulate their personal boundaries between online and offline contexts, avoiding “dissolution” in digital space, and maintaining continuity and integrity of the self in technologically mediated daily life, thereby transforming the challenges of digitalization into zones of personal development.

Profiles of the technologically enhanced personality. Cluster analysis identified four groups of respondents that differed in their scores across the subscales of the DDLSM-2 as well as in levels of happiness and hardiness: integrators, strategists, maladaptives, and minimalists. The first two profiles were the most well-adjusted in the context of cyber-physical everyday life and were also the most common in the sample, representing over seventy percent of participants. The first group, strategists, combines high integrity of the technologically extended personality with advanced strategic skills for managing digital devices, a critical attitude toward the digital environment, and relatively low engagement in digital sociality. This combination of traits provides the highest levels of happiness and hardiness within this profile. The second and largest group, integrators, also shows good well-being: moderate levels of integrity are paired with strong skills in managing digital devices, high significance of digital everyday life, and active engagement in the online social world. This combination supports social integration, effectiveness, and subjective well-being in a mixed-reality context. In contrast, the maladaptive group is characterized by lower scores across all DDLSM-2 subscales as well as reduced happiness and hardiness, making it relatively disadvantaged both digitally and psychologically. The fourth group, minimalists, demonstrates high levels of integrity and hardiness, yet low engagement in digital everyday life limits their opportunities for achievement and positive functioning in modern cyber-physical conditions, which may reduce their potential for experiencing happiness in the contemporary world. In this case, lower happiness should not be interpreted as a personal failure but rather as a potential cost of maintaining autonomy in a digital society. The highest levels of well-being and hardiness are achieved when a critical approach to the digital environment is combined with moderate or high engagement, while excessive restriction of digital participation or insufficient integrity is associated with risks of reduced adaptation and lower happiness. These findings contribute to understanding optimal strategies for the development of a technologically enhanced personality. This shows that within complex systems such as the personality in mixed reality, integrity is not a simple sum of its parts, and qualitatively different configurations of variables can exist across different types. The identified profiles do not represent ideal types but rather different adaptive strategies that individuals adopt in response to the challenges of mixed reality. Each profile reflects a unique balance between the benefits and costs of digitalization. To verify these types and understand the motivations and life strategies of respondents within each cluster, additional qualitative research is required.

The DDLSM-2 can be used in psychological counseling to assess adaptation challenges in mixed-reality environments and to develop individualized support strategies; in education and organizational settings to monitor digital aspects of student and employee well-being; and in academic research as a basis for further study of personality transformations in the context of digitalization and integration with technological extensions.

Conclusion

- A new version of the Digital Daily Life Self-Management Scale (DDLSM-2) was developed and tested, including a subscale Integrity of Personality. The scale demonstrated a reliable four-factor structure and confirmed its validity.

- The integrity of the technologically extended personality, theoretically defined through seven criteria (bodily self, identity, expansion of self-boundaries, autonomy, consistency of social norms, unity of value-meaning orientations, and self-knowledge), empirically manifests primarily through indicators of its disruption. This finding suggests that in the context of digitalization, integrity is experienced by the individual not as a given, but as a task requiring conscious resolution. Indicators of disrupted integrity help identify areas of current and near-term personal development related to mastery of digital tools as new psychological instruments, which in turn determines the effectiveness of digital daily life management and the potential for achieving a new form of integrity.

- A positive relationship was established between the integrity of the technologically extended personality and subjective well-being (happiness), resilience, and core beliefs, confirming its role as a key resource for adaptation and preadaptation in mixed-reality environments.

- Four profiles of the technologically extended personality were identified, differing in adaptive potential and well-being: “strategists,” “integrators,” “maladapters,” and “minimalists.” The most well-adjusted profiles are the strategists and integrators, combining high or moderate integrity with well-developed digital management skills. Identifying different adaptive strategies allows for a shift from studying simple linear relationships to analyzing complex, systemic configurations of personality within the new human development ecosystem.

- The results indicate that for psychological well-being and resilience in mixed-reality conditions, the critical factor is not minimizing digital engagement, but developing the capacity to manage digital extensions and integrate digital experiences into a coherent personal system while maintaining autonomy and connection to reality.

Limitations. A limitation of the study is the need for further verification of the scale on representative samples from various age groups and types of residence. Additionally, as the research was conducted on a Russian sample, the findings may be specific to that cultural and historical context.