Introduction

Executive functioning (EF) plays a central role in higher level complex activities such as learning, behavior control, goal-setting, problem-solving, planning and metacognition (Korzeniowski, Ison, de Anglat, 2021). Multiple studies have associated strong EF with school readiness (Ruffini et al., 2024) and academic success (Peng, Kievit, 2020; Spiegel et al., 2021), better employment status (Lemonaki et al., 2021), and good physical (Kalén et al., 2021) and psychological health (Diamond, 2013). Deficits in EF have been linked to several clinical outcomes such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression (Nuño et al., 2021), and psychopathologies (Zelazo 2020), including conduct disorder (Bonham et al., 2021) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Lopez-Hernandez et al., 2022; Zainal, Newman, 2022). In older individuals (> 60 years old), higher levels of EF have been associated with better daily functioning and aging well (Darby et al., 2017; Puente, Lindbergh, Miller, 2015). Conversely, lower levels of EF in elderly individuals have been associated with higher risk of mild cognitive impairment (Chen et al., 2017) and dementia (Junquera et al., 2020).

EF has a long developmental trajectory. EF skills emerge in infancy and develop through childhood into young adulthood with sensitive periods in early childhood and early adolescence (Diamond, 2013; Obradović, Willoughby, 2019). EF unfolds within the pre-frontal cortex (PFC), one of the slowest developing parts of the brain (Korzeniowski, Ison, de Anglat, 2021). This protracted progression from early emerging, basic cognitive processes into a complex system is highly influenced by children’s experiences. Children who grow up in deprived circumstances—for example due to chronic poverty, malnutrition, or illness— may be most vulnerable to delays or gaps in their EF development (Zelazo, 2020). The key role of EF in shaping outcomes throughout the lifespan, and its vulnerability during the long course of PFC development, make EF skills an important target for early intervention.

The acquisition and practice of early math skills (e.g., basic foundations of counting, addition, subtraction) have been linked with the development of EF. These findings pave the way for the development of mathematics instruction interventions that target skills of EF, particularly during early childhood when the brain is highly plastic and undergoing significant developmental changes. In this paper, we focus on EF skills and their co-development with mathematics to argue that high quality mathematics teaching activities constitute an appropriate and effective intervention for children’s foundational EF skills, particularly during preschool and early elementary education. Learning the basic principles of mathematics provides children with continuous, progressively challenging opportunities to engage EF skills and develop them as they learn and practice math.

Executive Functions: Definitions, Structure, and Development from Ages 0—6 Years Old

Only a handful of studies on the development of EF in preschool-aged children were generated in the 1980s and 1990s. The literature now includes hundreds of such studies (Kurgansky, 2022; Thériault‐Couture, Matte‐Gagné, Bernier, 2025). This body of research has established generally accepted definitions and models of EF and its component skills. It has also allowed researchers to devise a rough outline of their developmental course.

EF Definitions and Structure

The cognitive skills that underlie EF, or goal-directed behavior (Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000), are exerted when concentration, attention, and deliberate thought and action are needed rather than quick, impulsive or instinctive responses. The generally accepted core component skills of EF are (1) working memory, (2) inhibitory control of both attention and action, and (3) cognitive flexibility (Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000). Working memory involves holding information in mind when it is no longer perceptually present, updating it with new information, and mentally working with that information (i.e., transforming it, rearranging it, comprehending or composing it) for use or presentation later (Baddeley, Hitch 1994). Reading and listening comprehension rely on working memory, as does mental math (Diamond, 2013). Inhibition encompasses two components: response inhibition or self-control — resisting temptations, resisting acting impulsively; and interference control — selective attention and cognitive inhibition, the ability to ignore distractions or irrelevant information and maintain focus. Cognitive flexibility includes thinking creatively, seeing things from a different perspective (either spatially or from that of another person), and the ability to adapt to changing circumstances (Diamond, 2013).

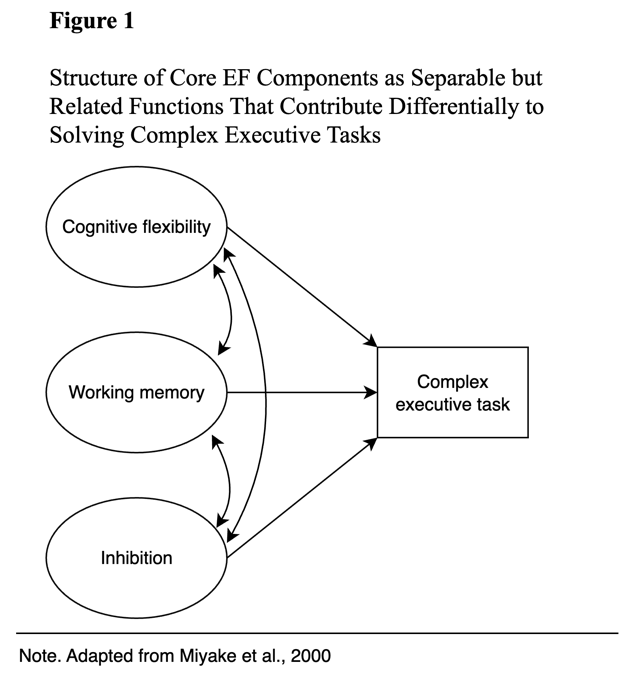

Seminal studies by Miyake et al. (2000) conducted with college students aimed to provide a compelling theory and model of EF (see Figure 1). Confirmatory factor analysis of student data from nine subtests suggested three separable but related EF components with a common underlying process—a so-called Common EF factor, possibly the necessary basis for all EF components (Friedman, Miyake, 2017). While the details of this EF model may be debated and are likely different at different stages of life and in different places around the world, this model provides a sufficient framework for a discussion of children’s EF development.

Fig. 1. Structure of Core EF Components as Separable but Related Functions That Contribute Differentially to Solving Complex Executive Tasks

Early EF Development

What we know about the development of EF in children is based primarily on studies carried out using Western-developed assessment paradigms. According to hierarchical models of development (Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000), EF develops by building upon simpler cognitive skills, such as attention and short term memory; the coordination of these simpler skills with core EF skills enable the execution of complex tasks (Miyake et al. 2000). Core EF components in their simplest forms start to develop in infancy and are all functional by the age of three years.

Response inhibition develops within the first year of life as demonstrated by children’s ability to stop an enjoyable activity when requested to by a caregiver (Kochanska, Tjebkes, Fortnan, 1998). Cognitive inhibition, which enables children to focus on certain stimuli while ignoring others, supports short-term memory before the age of one (Diamond, 2013). Updating and manipulating information held in mind, key aspects of working memory that also draw upon attention networks, have been documented in spatial memory tasks as early as 15 months of age (van Ede, Nobre, 2023). Around two years of age, coordination between working memory and response inhibition enable a child to hold a simple rule in mind to overcome a pre-potent response, such as placing yellow blocks into a red bucket, after having placed them into a yellow bucket multiple times before (Thériault‐Couture, Matte‐Gagné, Bernier, 2025). Cognitive flexibility builds on inhibitory control and working memory and so emerges later in children’s development, around the age of four or five.

Global Considerations for the Development of EF

Despite the large number of studies carried out on the topic, when and how children develop EFs are ongoing questions. The vast majority of this developmental research was carried out in the US and other Western settings, such as Canada, European countries, and the United Kingdom. Yet we know that children’s cognitive development is highly influenced by their experiences and environmental conditions (Munakata, Michaelson, 2021). A useful perspective proposed by Doebel is of EF development as the emergence of skills in the service of specific goals activated and influenced by knowledge, beliefs, norms, values and preferences that may be distinct in different contexts or settings (Doebel, 2020). Thus, while trajectories of EF development may be shaped by the biology of brain development, differences (in behavior and on EF test performance) may be observed due to children’s particular experiences in different settings. Understanding these differences has important implications for how interventions for EF may be developed and implemented effectively in different settings.

EF Interventions for Young Children

There have been by now more than 100 intervention studies targeting EF in children described in many systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Diamond, Ling, 2016; Takacs, Kassai, 2019). While some reviews have been broad and inclusive, others have focused on specific intervention types, such as training of working memory using digital technology (Scionti et al., 2020); mindfulness-based interventions (Bockmann, Yu 2023; Pearce et al., 2025); or physical activity (Wang et al., 2023; Wood et al., 2020). We highlight a recent review/meta-analysis of 85 EF intervention studies (published from 2000-2020) implemented in preschool classrooms with typically developing children (ages 3-6 years old; Muir, Howard, Kervin, 2023).

The interventions reviewed by Muir and colleagues were highly diverse in the nature and content of each intervention, how it was delivered, dosage, and the measures used to evaluate efficacy, reflecting the myriad ways that EF can be addressed in the pre-school setting. The most commonly studied interventions involved mediated structured play (n = 16), mindfulness (n = 12) and physical activity (n = 12). Notably, though, out of the 85 studies, only four included a follow-up assessment several months following the intervention (Clements et al., 2020: math in the USA; Keown, Franke, Triggs, 2020: mediated structured play in New Zealand; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016: mindfulness in the USA; Rosas et al., 2019: mediated structured play in Chile). All other studies evaluated intervention effectiveness only immediately after completing the intervention. Additionally, only four of the reviewed interventions addressed EFs using mathematics instruction (Clements et al., 2020; Kroesbergen, van Luit, Maas, 2004; Kyttälä, Kanerva, Kroesbergen, 2015; Passolunghi, Costa, 2016). As a group, mathematics interventions were judged to be among the weakest approaches by Muir and colleagues, based on their collective efficacy. We argue, however, that mathematics learning has high potential to strengthen executive functioning during early childhood, the optimal time to intervene. First, the neural circuits for knowledge building in mathematics are present at birth and are ready to be developed further when children reach school age. Second, all mathematical activities require EF at some level (Platas, 2024). Further, interventions that foster EF implicitly in everyday activities, such as math-learning, are more enjoyable and easier to implement than explicit EF training (Takacs, Kassai, 2019), and the development of basic math skills takes place over 1—2 years, providing the opportunity for a long-term, regularly administered intervention.

The Architecture for Math Knowledge-Building is Present at Birth

The human brain is endowed with an innate mechanism for apprehending numerical quantities, one that is inherited from our evolutionary past and that guides the acquisition of mathematics… In the first year of life, then, babies should already understand some fragments of arithmetic.

Dehaene, The Number Sense, p. 41(1997)

The innate ontology of mathematical thinking provides an ever-present platform for the teaching of basic mathematics. All animals, including humans are born with a “number sense,” (Dehaene, 1997; Krasa, Tzanetopoulos, Maas, 2022) — brain systems that recognize quantity as important and therefore have the neural architecture to pay attention to it (Krasa et al., 2022). This is evident in infants’ sensitivity to changes or differences in quantity. Even as young as two to three days old, an infant exposed repeatedly to a picture of two dots, to the point of losing interest, will show renewed and heightened interest (look longer) at a picture showing three dots (Dehaene, 1997). Infants’ ability to distinguish quantities, it turns out, happens with objects of any kind, sounds, as well as motion (Spelke, 2022). Infants have also exhibited understanding of addition and subtraction: when they see one object placed behind a screen, then another, they expect to see two objects when the screen is lifted. They have similar correct expectations when they see objects being taken away (Wynn, 2022). Thus, long before school, children have developed foundations of mathematical thinking. Without any knowledge of numerals or number names, children will order or rank sets of objects or lengths of objects (sticks or rods) by size. Before attending school, many children will master the meaning of the common quantitative words such as more, bigger, longer, with respect to objects as well as abstractions such as time (Krasa, Tzanetopoulos, Maas, 2022). All of this knowledge primes children for learning mathematics in school.

The Dynamic Co-Development of Mathematics and Executive Functioning

Formal elementary mathematics education starts with securing children’s conceptual understanding of quantity, how quantities relate to each other, and the language and symbolic system (numerals) that we use to represent quantity (Krasa, Tzanetopoulos, Maas, 2022). At these earliest levels of learning, simple math processes can be matched to specific cognitive skills. For example, working memory has been associated with magnitude comparison (Nelwan et al., 2022), ordering (Finke et al., 2021), and estimation on a number line (Namkung, Fuchs, 2016). The field of education is replete with studies on EF as a precursor to and supporting factor for math achievement (Bull, Lee 2014; Cragg, Gilmore 2014). More recent research has confirmed that EF exhibit correlated and reciprocal growth, or co-development, with math skills during early childhood (Coolen et al., 2021; Miller-Cotto, Byrnes, 2020).

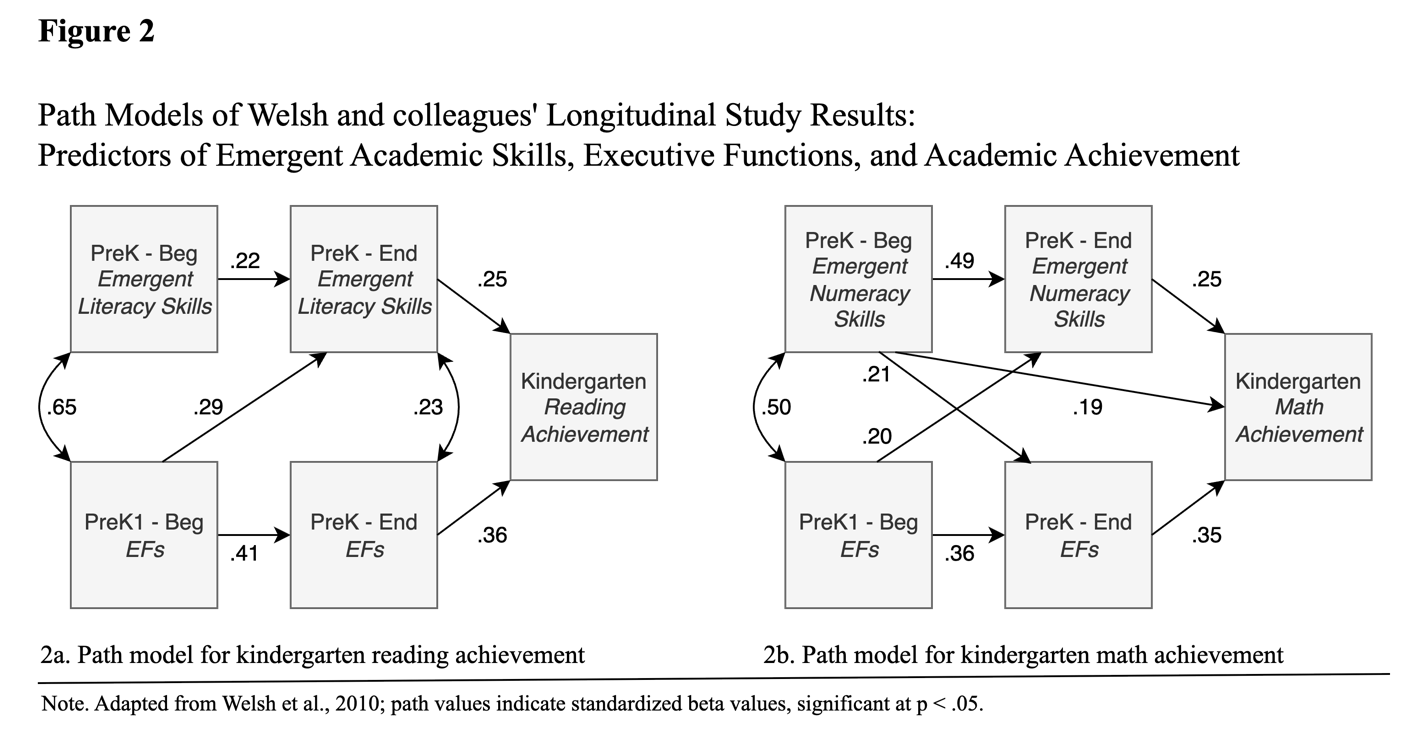

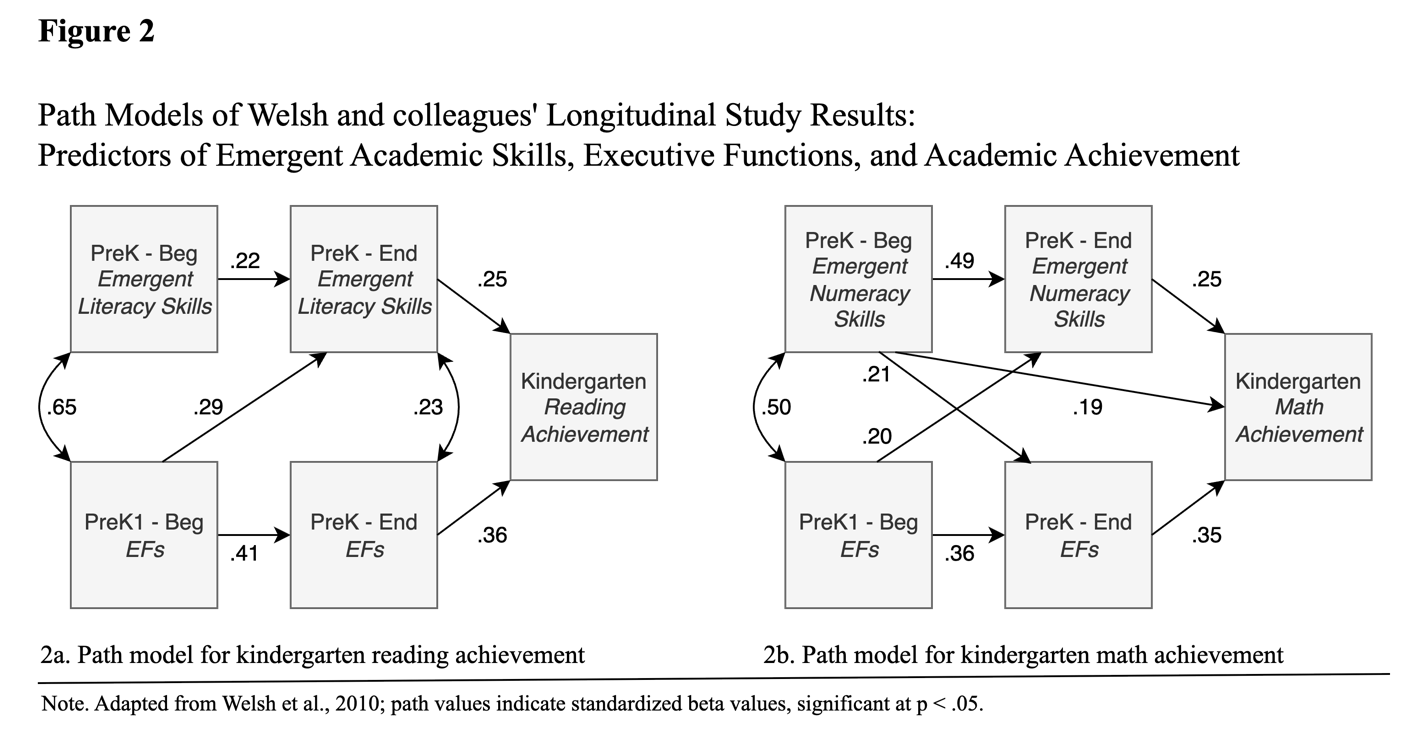

One of the first studies to indicate this bi-directional relationship was originally aimed to investigate whether working memory and attention control (early components of EF) would predict concurrent growth in emergent literacy and numeracy skills across a year of pre-kindergarten, with effects persisting to the end of kindergarten (Welsh et al., 2010). The children (n = 149, mean age 4.49 years old, SD 0.31; range: 3.72–5.65) were enrolled in Head Start and came from diverse backgrounds; 68% had incomes below the national poverty level. Assessments delivered during the pre-kindergarten year (Time 1 and Time 2) targeted emergent literacy skills and emergent numeracy skills. At the end of kindergarten, children were assessed on early reading and on math achievement. No interventions had been implemented. Results in longitudinal models showed that growth in EF during pre-kindergarten predicted end of kindergarten reading and math achievement, controlling for growth in children’s emergent literacy, numeracy, and language skills during pre-kindergarten, as expected. Unexpectedly, emergent numeracy skills at the beginning of pre-kindergarten predicted EF at the end of pre-kindergarten—a relationship not observed in the parallel model of developing literacy skills (see Figure 2; Welsh et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies employing multiple timepoints in cross-lagged models have since further supported the bidirectional relationship between math and EF (Zhang, Peng, 2023).

Fig. 2. Path Models of Welsh and colleagues' Longitudinal Study Results: Predictors of Emergent Academic Skills, Executive Functions, and Academic Achievement

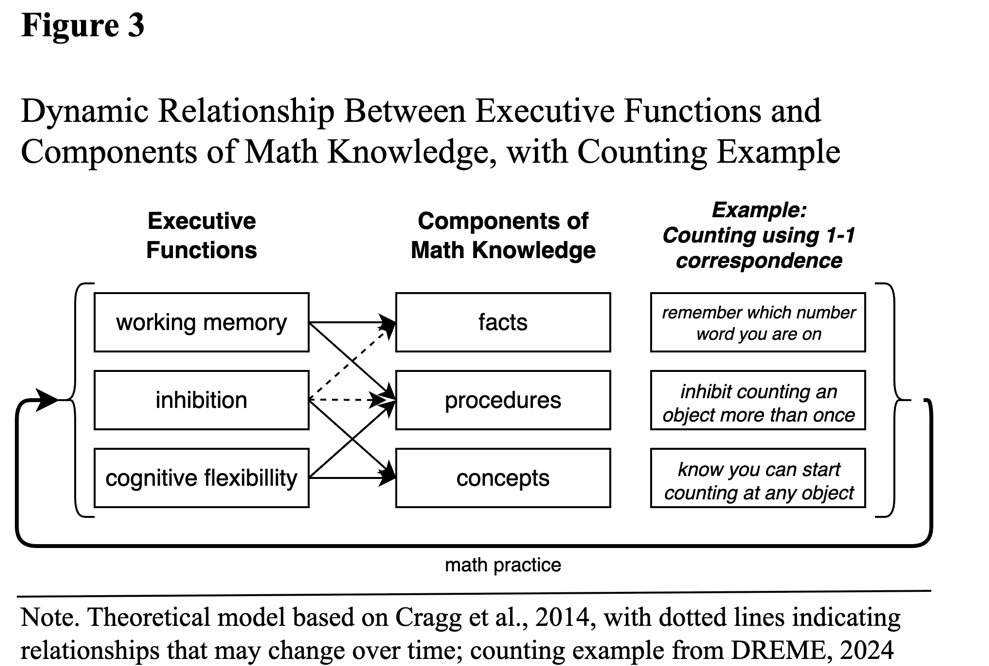

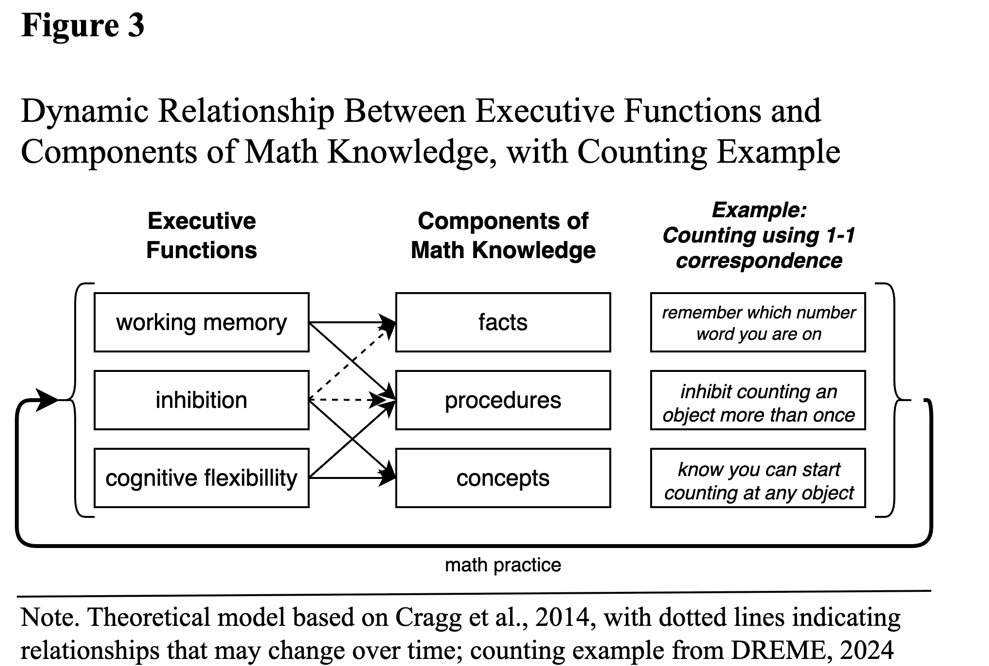

Since the work of Welsh and colleagues (2010), researchers have sought to illustrate, both theoretically and empirically, how EF skills are elicited, challenged, and practiced when doing math. Figure 3 presents an augmented version of Cragg and colleagues’ theoretical model of the EF-math relationship combined with an explicit example of how the basic task of counting objects in a set using one-to-one correspondence (assigning one number to one object) calls upon working memory, cognitive inhibition, and cognitive flexibility (Platas, 2024). The structure of mathematics provides logical, incremental ways to challenge and grow children’s EF in developmentally appropriate ways.

Fig. 3. Dynamic Relationship Between Executive Functions and Components of Math Knowledge, with Counting Example

EF challenge may be leveled up in counting, for example, by adding more objects to count, changing the physical arrangement of the objects (e.g., from an ordered array to a random arrangement), or asking the child to start counting at different objects.

Mental arithmetic and its links to EFs can be broken down in a similar way. When adding two numbers together without writing them down, one uses working memory to remember the two numbers while adding them together, then to remember the result. Working memory demand can be incrementally increased by increasing addends (e.g., 2 + 3 + 4 + 7). Tracking the new information, the new total after 3 digits (9) and letting go of the old total after two digits (5), is an example of updating, a key feature of working memory tasks. Further, cognitive flexibility can come into play if one is asked to use different approaches, such as regrouping [(7 + 3 = 10) + (2 + 4 = 6)], to solve the problem more efficiently (Krasa, Tzanetopoulos, Maas, 2022).

Math Interventions for Executive Functioning for Young Children

The field of interventions that target EF in young children using math activities (Clements et al., 2020; Kroesbergen, van Luit, Maas, 2004; Kyttälä, Kanerva, Kroesbergen, 2015; Passolunghi, Costa, 2016; Scerif et al., 2025) is small and still nascent, but some approaches have shown some promise (Muir et al. 2023). Table 1 presents a summary of the known tested EF-math interventions.

Table 1

Published Math-based EF Intervention studies, 2000—2025

|

Author/ Year

|

Clements et al. (2020)

|

Kroesbergen van Luit, Maas, (2014)

|

Kyttala et al. (2015)

|

Passolunghi, Costa (2016)

|

Scerif et al. (2025)

|

|

Country

|

USA

|

Netherlands

|

Finland

|

Italy

|

UK

|

|

Study Design

|

RCT

|

Quasi-experimental

|

Quasi-experimental

|

Quasi-experimental

|

RCT

|

|

Sample

|

837

|

51

|

61

|

48

|

193

|

|

Age Range

|

Not reported

|

5 to 6

|

5 to 6

|

5 to 6

|

41-54 months

|

|

Hours

|

260

|

4

|

4

|

10

|

12

|

|

Program Dose and Duration

|

5 hr/week

1 year

|

2 x 30 mins/wk 4 weeks

|

2 x 30 mins/wk 4 weeks

|

2 X 1 hr/wk

5 weeks

|

3 x 20 mins/wk 12 weeks

|

|

Interventionist

|

Teacher

|

External Facilitator

|

External Facilitator

|

External Facilitator

|

Teacher

|

|

Outcome Variables

|

IC x 2, WM x 2

|

WM x 2

|

WM x 6

|

WM x 2

|

IC x 2, WM x 2, SH x 2

|

|

ES Magnitude

|

Small

|

Moderate - Large

|

Small

|

Large

|

Moderate - Large

|

|

Intervention description

|

Building Blocks (BB) curriculum adopted for the school year; plus an augmented condition of BB + Tools of the Mind

|

Adapted from remedial program for multiplication and division.

|

Training games played in small groups of children (4-7)

|

8 games, 2 of 4 types: verbal WM, verbal STM, visuospatial WM, visuospatial STM; groups of 5 children at a time

|

25 different activities targeting EFs in various math-related activities

|

Note: ES = effect size; RCT = randomized controlled trial; IC = inhibitory control; WM = working memory; SH = set shifting; STM = short-term memory.

General statements about the potential long term effectiveness of these interventions are difficult to make given the various sample sizes, methods of implementation, and dosages. However, it is worth noting that although effects sizes were small for the BB alone condition at the end of the intervention period, this condition also appeared to promote better math and EF skills one year later, suggesting potential long term effects of a high quality early math curriculum on both math skills and EFs (Clements et al., 2020). In a previous study of BB implemented during a year of pre-kindergarten, the impacts of BB on language, literacy, and mathematics were in the moderate-to-large range (effect sizes 0,45—0,62), and EF impacts were in the small range (0,20—0,27). These results are consistent with a “spill-over” hypothesis, which posits that high quality academic curricula targeting early reading and math skills support the acquisition of reading and math, concurrent with cognitive skills that are routinely exercised as children learn (Weiland, Yoshikawa, 2013).

Conclusion

We conclude that these early attempts at math-EF interventions are worth learning from and building upon as mathematics is a neurodevelopmental companion to EFs. We return to Doebel’s notion that EF development unfolds in the service of specific, contextually-driven goals (Doebel, 2020), that is, in meaningful activities. Mathematics learning is driven by universally meaningful learning goals, such as the goal of counting to find out “how many” (Clements, Sarama, 2021). Math learning provides a highly appropriate mechanism for EF development, one that is meaningful anywhere in the world.