Introduction

Students' academic success is not solely attributable to their intellectual abilities. Instead, success is associated with personal, biological, psychological, and social factors that play a vital role. The psychological factors are motivation, concentration, attention, attitude, memory, critical thinking, determination, perseverance, emotional state, organization, problem-solving ability, self-management, and self-regulation skills [Furman, 2023]. Self-regulation, in particular, has been shown to explain how students achieve academic success by regulating their behavior to benefit academic activities. Self-regulation is considered the result of cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes. Specifically, Zimmerman [Zimmerman, 1989] defined it as the degree to which students are motivationally, metacognitively involved, and behaviorally active in their learning by changing personal and environmental conditions. Self-regulation is not about mental ability or performance but the self-direction process by which students transform their mental abilities into academic ones. Self-regulation involves goal-oriented thoughts, feelings, and behaviours [Zimmerman, 1989], which foster academic success through effective study tools and strategies [Zimmerman, 2008]. On the other hand, if a student struggles to complete a task within the allocated time frame, we are referring to procrastination, a phenomenon that significantly contributes to academic failure.

Self-regulation in Procrastination

Procrastination, a topic extensively studied in psychology [Sharma, 2020], refers to the deliberate delay of tasks, which can lead to negative psychological outcomes. It represents a deficiency in self-regulation, which can hinder learners' time management [Hamim, 2022]. This behavioural pattern signifies poor self-regulation skills [Elizondo, 2024]. Academic self-regulation involves goal-setting and managing motivations, thoughts, emotions, and actions. Procrastination can cause dissatisfaction, psychological vulnerability, and academic risks [Elemo, 2023]. Self-regulation has been considered part of procrastination from a theoretical and empirical perspective [Wang, 2023]. Procrastination involves postponing tasks and self-regulating academic tasks [Dominguez-Lara, 2014]. Effective self-regulation, time management, and goal-setting can reduce procrastination, ensuring timely completion of assignments.

Chronic procrastinators often underestimate the time required to complete tasks, fail to prepare adequately, and spend less time gathering information. Their lack of self-regulation skills is evident in difficulties with knowledge management, cognitive processes, metacognition, self-efficacy, self-esteem, stress, fear of failure, and anxiety [Barutçu, 2020; Khairun, 2023]. Empirical evidence suggests that procrastinators engage in self-sabotage, make excuses, and exhibit poor self-regulation of performance [Birol, 2019].

Self-efficacy and Affect

According to the self-regulation model, self-efficacy is a critical variable. Self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their ability to perform a given task [Bandura, 1977]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that self-efficacy significantly correlates with self-regulation and predicts academic success due to its motivational nature [Rahmania, 2023]. Additionally, self-efficacy influences academic behavior and predicts self-regulation [Do, 2023]. However, few studies have analyzed the interaction between self-efficacy and self-regulation.

Affect is not limited to an emotional state but comprises various phenomena, including affective disposition, mood, and emotions. Furthermore, affect is associated with specific capabilities and skills such as emotional regulation, emotion management, and impulse control. Moreover, research has shown that affect directly impacts attention, memory, analysis, and information processing [Fu, 2022], consequently affecting student performance. Affective states are crucial in complex cognitive processes and the self-reflection phase of self-regulation. Self-regulation of learning is a challenge that requires students to develop skills and abilities. Positive affect can improve behavior and commitment to academic success, and recent studies have shown that positive affective state and interpersonal affective regulation are positively related to self-efficacy [Duru, 2023].

Emotional affect is considered a primary source of self-efficacy, which determines behavior and affective reactions [Bandura, 2001]. Individuals with high self-efficacy tend to seek challenging tasks that produce satisfaction and positive affect [Motro, 2021; Prifti, 2022]. In contrast, low self-efficacy produces negative consequences [Mielniczuk, 2020]. Positive affect mediates self-efficacy and behavior, enabling behavioral self-regulation and stress reduction [Krok, 2020; Mielniczuk, 2020]. Affect has a direct effect on self-efficacy and has mediated variables such as burnout [Wang, 2022], psychological well-being [Krok, 2020], and innovative behavior [Mielniczuk, 2020]. Its potential to drive self-perception, self-esteem, self-concept, motivation, self-efficacy, and behavioral control allows affecting to be considered a mediating or predictor variable in empirical studies.

The Present Study

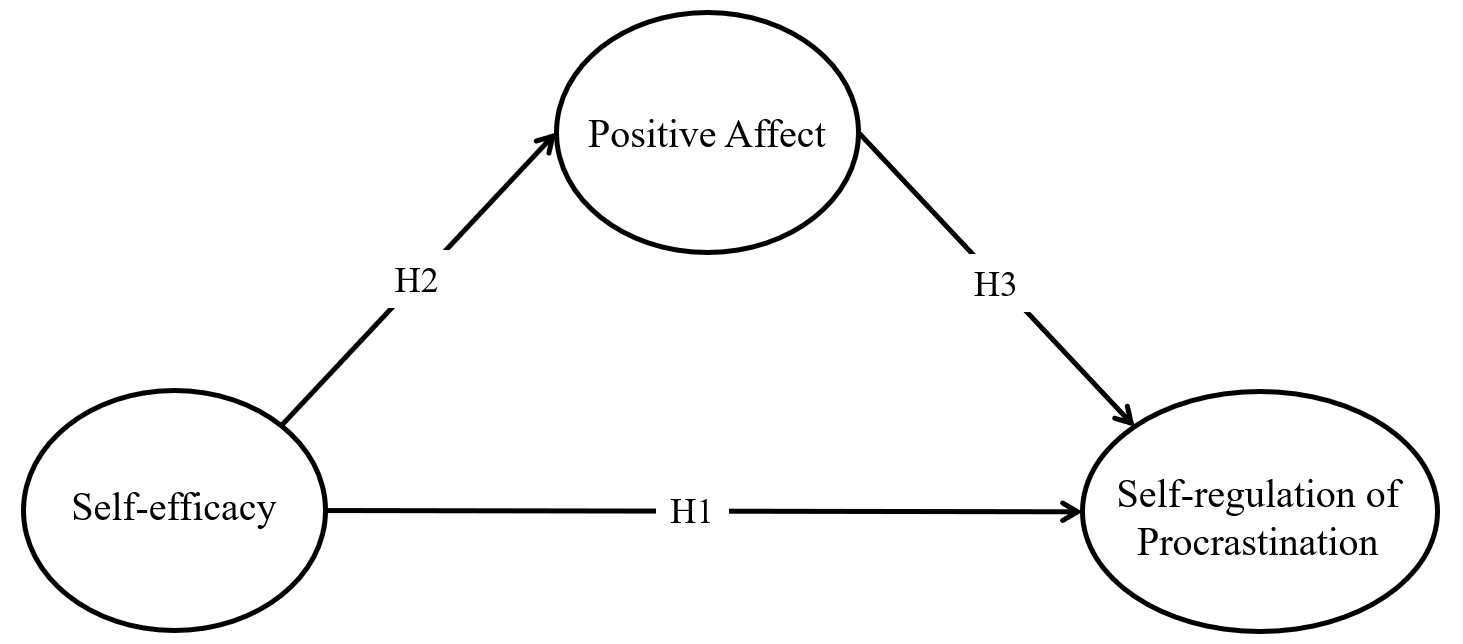

Based on the integration of studies variables, a self-regulation model of procrastination was developed, focusing on self-efficacy and positive affect's impact. Hypotheses were formulated for the initial model: H1) Self-efficacy positively predicts self-regulation, H2) Self-efficacy positively predicts positive affect, and H3) Positive affect positively predicts self-regulation (Fig. 1). Further hypotheses on indirect and total effects of affect were proposed: H4) Self-efficacy indirectly influences self-regulation through positive affect, and H5) Self-efficacy's total impact on self-regulation is mediated by positive affect.

Fig. 1. Hypothesized Model

The proposed model must demonstrate invariance to assess whether the relationships between model variables remain consistent across diverse groups or contexts, such as various age groups, cultures, or procrastination scenarios. Conflicting views exist in the literature regarding the link between procrastination and self-efficacy, particularly concerning gender differences. While some studies suggest that men tend to procrastinate more [Lu, 2022], others argue the opposite, with women displaying higher levels of procrastination [Li, 2020]. This disparity impedes reaching a consensus.

Conversely, studies consistently show that men exhibit higher levels of self-efficacy than women [Tang, 2023], a finding supported by meta-analyses [Huang, 2013]. These gender differences pose challenges, requiring advanced modeling techniques to account for gender-specific functionality. It is relevant to compare not only based on gender but also between those who solely study and those who study and work to gather comprehensive insights. Therefore, two invariance hypotheses were proposed: H6) The model is gender-invariant; H7) The model is invariant for individuals who study and work and those who solely study.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 1224 Peruvian university students through a non-probabilistic sampling using inclusion criteria: over 18 years of age, enrolled in the 2022 academic year, studying at the undergraduate level, from different shifts and academic cycles. A total of 38,5% were male and 61,5% female. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 49 years (M=22,9 years; SD=5,48 years). Among those evaluated, 75,6% were single, 20,5% cohabiting, 3,5% married, 0,4% divorced. Likewise, 52,4% were only studying while 47,6% were studying and working. The students belonged to careers in social sciences, health and engineering at a university.

Measures

The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) measures both positive and negative affect in individuals with 12 items: six for positive affect (PA) and six for negative affect (NA). Responses range from 1 (very rarely or never) to 5 (very often or always). The PA items explained 69,49% of the variance and the NA items 61,56%. The reliability coefficients were α=0,91 for PA and α=0,87 for NA. In a Peruvian sample, the scale showed reliability coefficients of ω=0,86 for positive affect and ω=0,79 for negative affect, indicating its applicability [Cassaretto, 2017].

The Academic Situations Specific Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (EAPESA) consists of 10 items with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After linguistic adaptation and AFE, a general factor emerged. A subsequent CFA confirmed goodness of fit and reliability indices (RMSEA=0,091; CFI=0,990; α=0,93, ω=0,95), supporting the nine-item unidimensional model [Dominguez-Lara, 2023]. Response reliability in the sample was also assessed, yielding good alpha (0,90) and omega (0,90) indices.

The Academic Procrastination Scale (EPA), version Dominguez-Lara et al. [Dominguez-Lara, 2014], was used, which consists of 12 items with five-point Likert-type responses. It is composed of two factors: procrastination and academic self-regulation. The scale demonstrated adequate model fit of two correlated dimensions, as well as adequate reliability indices for the procrastination (ω=0,81) and self-regulation (ω=0,89) factors. However, inconsistencies were found with item 4, which had weak correlations with the other items, and its factor loading was only 0,27, indicating a poor representation of its factor. As a result, the item was removed, and adequate fit indices were obtained (CFI=0,92; SRMR=0,03; RMSEA [CI 90%]=0,06 [0,05–0,07]). Reliability for procrastination (ω=0,80) and self-regulation (ω=0,82) remained within expectations.

Procedure

Permission was requested from the university of origin of the principal author for the application of the battery of instruments through a virtual form, which consisted of: 1) Informed consent; 2) sociodemographic and academic information; 3) measures. For dissemination, teachers were asked to help disseminate the survey. Data collection was established over three months between October and December 2022.

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using R Studio version 4.2.2. First, we conducted a preliminary examination of the data by assessing measures of central tendency, dispersion, and normality statistics such as skewness and kurtosis. Next, we examined correlations to ensure there was no multicollinearity (correlation<0,80) between variables. To assess discriminant validity, we used the average variance extracted (AVE) [Fornell, 1981].

The robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) was used, considering the five response options of the items as a continuous variable [Rhemtulla, 2012]. Goodness of fit indices, including chi-squared (χ2), degrees of freedom (df), CFI, TLI, RMSEA with 90% confidence intervals, were used for model evaluation [Browne, 1992]. Criteria for acceptable fit included CFI and TLI>0,90 and RMSEA<0,08 with CI90%. Effect size (f 2) was calculated according to Cohen's criteria: small (0,02), medium (0,15), and large (0,35) effects [Cohen, 1988]. Standardized (β) and unstandardized (β) regressions were computed, the latter using bootstrapping (10000 resamples) to obtain 95% confidence intervals. Direct, indirect, and total model effects were assessed accordingly.

The last analysis was the invariance of the model between gender and educational status. Byrne's suggestions for metric invariance restrictions were followed [Byrne, 2016]: unrestricted configural; metric with restricted factor loadings; scalar with restricted intercepts; strict with restricted residuals. Evermann [Evermann, 2010] recommendations to ensure structural invariance were followed: restrictions on variance and covariance of latent variables and restrictions on regressions between latent variables. The criteria above were used to evaluate the models. Likewise, the comparison between restricted models used the changes in ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA where the ΔCFI must be less than 0,01 and the ΔRMSEA less than 0,05 [Cheung, 2002].

Results

Preliminary Analysis

In this study, the normality of the items within each latent variable was first assessed. Items related to self-efficacy, self-regulation, and positive affect exhibited negatively skewed kurtosis, indicating values above the mean. Skewness values were within the acceptable range of ±1,5, confirming their normal distribution. Latent means and standard deviations of the variables were also evaluated, as shown in Table 1. The reliability coefficients (alpha and omega) for all three variables were optimal, exceeding 0,70.

Significant moderate correlations were found between the latent variables. Discriminant validity was assessed using AVE, with values higher than the correlations, indicating variable independence. The criterion of multicollinearity, with correlations below 0,80, confirmed its absence.

Table 1. Descriptive, Reliability, Correlation and AVE of Latent Variables

|

|

M |

SD |

α |

ω |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1. Self-efficacy |

4,10 |

1,00 |

0,89 |

0,90 |

0,71 |

|

|

|

2. Self-regulation |

3,63 |

0,77 |

0,80 |

0,80 |

0,56 |

0,61 |

|

|

3. Positive affect |

3,87 |

0,63 |

0,86 |

0,86 |

0,48 |

0,43 |

0,71 |

Note: M=mean; SD=standard deviation; AVE (in diagonal italics).

Model Analysis

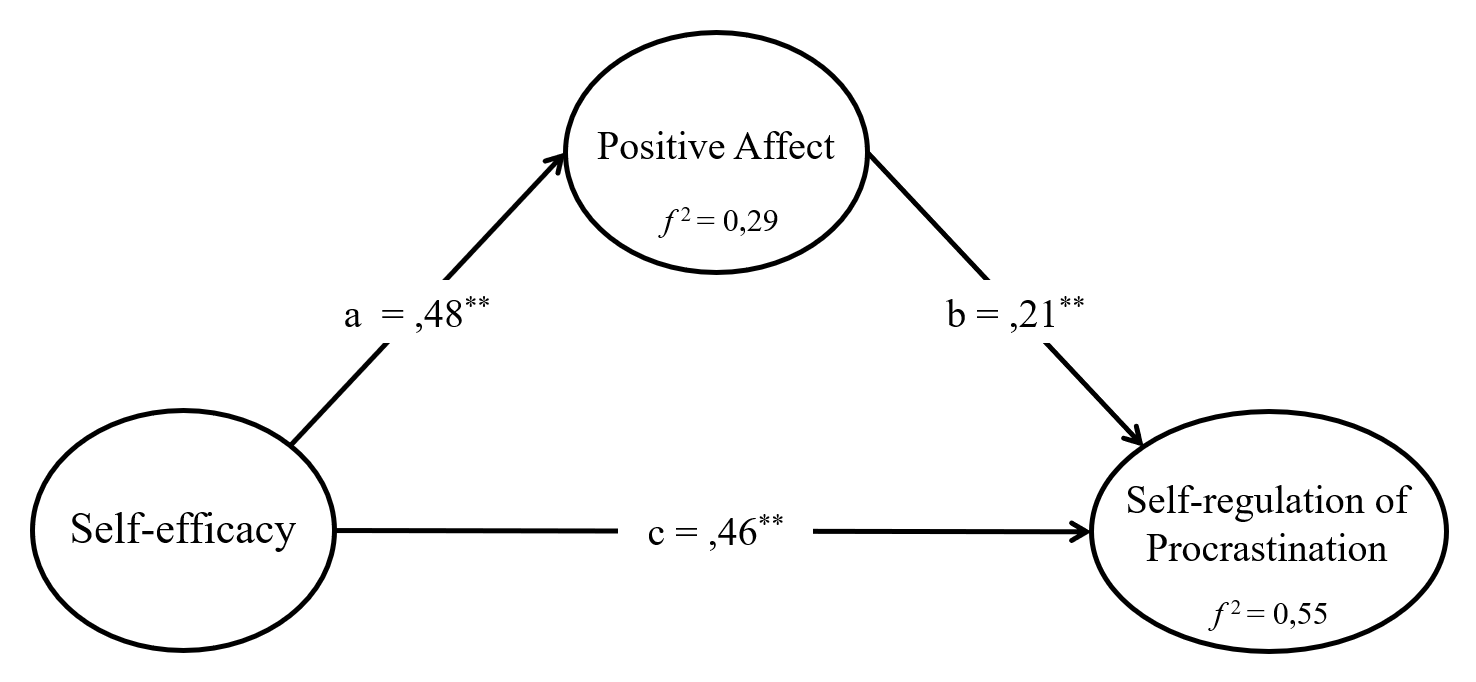

The study tested the hypothesized regression model (Fig. 2) and evaluated its fit indices, which were found to be adequate (Table 2). Therefore, the model was deemed representative of the university student sample. Standardized coefficients of the regressions were depicted in Fig. 2, and bootstrapping technique was used to obtain confidence intervals of the regression coefficients. Results showed that self-efficacy had a positive effect on self-regulation (β=0,36, CI[0,29–0,44]) and positive affect (β=0,50, CI[0,42–0,59]), supporting H1 and H2. Additionally, the direct effect of positive affect on self-regulation was positive (β=0,16, CI[0,10–0,22]), which corroborated H3.

Fig. 2. Direct, Indirect, and Total Effect

On the other hand, a statistically significant indirect effect of self-efficacy on self-regulation was found (β=0,10, p<0,001, β=0,08, CI[0,05-0,12]). However, when the direct effect (c) was added, the total model effect was strong (β=0,56, p<0,001, β=0,44, CI[0,37-0,52]), demonstrating a stable predictive power of self-efficacy directly and indirectly on self-regulation through positive affect. Figure 2 shows that for positive affect, the effect size was medium (f2=0,29), and the variance explained was 22,6%. For self-regulation, the effect size was large (f2=0,55), and the explained variance was 35,4%.

Model Invariance

The models were evaluated independently for sex and employment status, as shown in Table 2. The results indicated that both men and women, as well as those who only study or both study and work, had adequate fit indices (CFI>0,90, TLI>0,90, RMSEA<0,08). In addition, the sex invariance model demonstrated minimal variations between the configural, metric, scalar, strict, variance-covariance, and latent regressions, as indicated by the ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA indices. The same was observed when examining invariance by employment status groups. These minimal changes, as expected, demonstrate that the model is invariant in both groups, indicating that the interpretations in the model are equitable across groups.

Table 2. Model fit and invariance index of the models

|

Models |

χ2 (df) |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

IC 90% |

ΔCFI |

ΔRMSEA |

|

|

Study Model |

579,23 (206)* |

0,956 |

0,950 |

0,038 |

[0,035-0,042] |

|

|

|

|

Independent Groups |

|

|||||||

|

Men |

290,02 (206)* |

0,973 |

0,970 |

0,029 |

[0,022-0,036] |

|

|

|

|

Women |

461,49 (206)* |

0,952 |

0,946 |

0,041 |

[0,036-0,045] |

|

|

|

|

Only study |

407,78 (206)* |

0,956 |

0,951 |

0,039 |

[0,034-0,044] |

|

|

|

|

Study and work |

418,49 (206)* |

0,944 |

0,938 |

0,042 |

[0,037-0,047] |

|

|

|

|

Gender Invariance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M1 |

747,70 (412)* |

0,960 |

0,955 |

0,036 |

[0,033-0,040] |

|

|

|

|

M2 |

778,30 (431)* |

0,959 |

0,956 |

0,036 |

[0,033-0,040] |

0,001 |

0,000 |

|

|

M3 |

803,91 (449)* |

0,958 |

0,956 |

0,036 |

[0,032-0,040] |

0,001 |

0,000 |

|

|

M4 |

824,66 (472)* |

0,958 |

0,959 |

0,035 |

[0,031-0,390] |

0,000 |

0,001 |

|

|

M5 |

826,15 (475)* |

0,958 |

0,959 |

0,035 |

[0,031-0,038] |

0,000 |

0,000 |

|

|

M6 |

827,17 (478)* |

0,958 |

0,960 |

0,035 |

[0,031-0,038] |

0,000 |

0,000 |

|

|

Educational Status Invariance |

|

|||||||

|

M1 |

826,50 (412)* |

0,951 |

0,945 |

0,041 |

[0,037-0,044] |

|

|

|

|

M2 |

851,97 (431)* |

0,950 |

0,946 |

0,040 |

[0,036-0,044] |

0,001 |

0,001 |

|

|

M3 |

906,47 (449)* |

0,946 |

0,944 |

0,041 |

[0,037-0,044] |

0,004 |

0,001 |

|

|

M4 |

964,82 (472)* |

0,941 |

0,943 |

0,041 |

[0,038-0,045] |

0,004 |

0,001 |

|

|

M5 |

975,39 (475)* |

0,941 |

0,942 |

0,041 |

[0,038-0,045] |

0,001 |

0,000 |

|

|

M6 |

978,09 (478)* |

0,941 |

0,943 |

0,041 |

[0,038-0,045] |

0,000 |

0,000 |

|

Notes: M1=Configural; M2=Metric; M3=Scalar; M4=Strict; M5=Variance-covariance; M6=Latent regressions, *p<0,001.

Discussion

This study investigates the role of self-regulation in procrastination, exploring the contribution of self-efficacy in a theoretical model. The results of this study largely replicate previous research on the relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulation [Kurtovic, 2019; Rahmania, 2023], where self-efficacy acts as a driving force on behavior regulation. Students who are unable to regulate their behavior are more prone to procrastination, which leads to postponed or incomplete tasks [Mansouri, 2022]. It is known in psychological science: self-efficacy indirectly influences self-regulation through positive affect, which is consistent with Bandura's theoretical view of the influence of self-efficacy on cognitive, motivational, decision-making, and affective processes [Bandura, 2012]. Emotions play a crucial role in self-regulation, especially in the self-evaluation stage where they influence goal setting, strategy planning, and performance [Balashov, 2023]. It is known that students with low self-efficacy may struggle to regulate their behavior because they may lack the motivation and planning necessary to initiate and maintain academic performance.

Irrational beliefs can significantly increase insecurity and procrastinative behavior, which can have a negative impact on emotional stability and emotion-based learning [Duru, 2023; Rahimi, 2023]. In contrast, students with high self-efficacy and emotional stability are more likely to engage in regulated behaviors, exhibiting personal initiative, goal-setting, and persistence [Zimmerman, 2002]. Conversely, academic success is more likely with increased behavioral regulation and decreased affective regulation [Koh, 2022].

The model shows that self-efficacy has a significant impact on behavior regulation, which leads to improved goal-setting, strategic planning, and efficient task execution. This, in turn, reduces procrastination and promotes timely task completion. On the other hand, research suggests that procrastination can be worsened by factors such as disinhibition. This is supported by positive correlations with traits like irresponsibility, impulsivity, and distractibility, which contribute to decision-making procrastination [Cruz, 2023]. This behavior has a negative impact on self-regulated learning, making it difficult for procrastinators to effectively manage their learning [Saad, 2020]. However, it is possible to mitigate these negative effects and potentially improve academic performance by strengthening self-regulation skills, such as goal-setting and perseverance [Elizondo, 2024].

Furthermore, individuals who struggle with managing their emotions are more likely to procrastinate. Therefore, it is crucial to improve emotional regulation skills to decrease procrastination [Ludwigsen, 2023]. It is worth noting that our model showed consistency across gender and employment status, despite discrepancies found in previous research [Huang, 2013; Li, 2020; Lu, 2022; Tang, 2023]. Our model appears to be applicable across diverse groups, allowing for generalization of interpretations for males, females, and students who are working and/or studying.

In general, our study highlights the critical role of self-efficacy and affect on self-regulation and procrastination and underscores the importance of emotional stability and efficacy beliefs for academic success. However, broader participant inclusion is necessary to ensure more robust conclusions [Mejia, 2023].

Limitations. The study has limitations, including the use of non-probability sampling, which cautions against broad interpretations. Additionally, self-report instruments may introduce social desirability bias and are difficult to control for error. Unequal sample sizes in invariant models and testing only one model are also limitations. Future studies should replicate findings using probability sampling and address these limitations in order to draw more robust conclusions.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the study's proposed hypothetical model is supported by both theoretical and empirical literature. The model shows that self-regulation, a component of procrastination, is directly influenced by self-efficacy and affect. Additionally, self-efficacy indirectly affects procrastination through affect, suggesting that individuals with high self-efficacy can manage their behavior and avoid procrastination by maintaining positive emotions. This highlights the significance of cognitive and emotional skills in regulating behavior. The model's ability to remain consistent across different genders and educational backgrounds indicates that procrastination, self-regulation, self-efficacy, and positive affect are understood similarly by diverse groups. This makes the model's interpretations useful for men, women, students who are solely studying, and those who are working and studying at the same time. The empirical model can be used as a framework for interventions in personal growth workshops. Educational professionals, psychologists, and psychopedagogues can enhance students' abilities by addressing cognitive and emotional aspects indirectly through this model. Additionally, the study suggests further exploration in other domains to investigate how cognitive and emotional interventions can promote regulated behaviors.