Introduction

This Research on values indicates a growing number of individuals reflecting on happiness and the meaning of life (Norris & Inglehart, 2011). Happiness is widely regarded as a key indicator of human experience (Argyle, 2003). However, relatively few people consider themselves truly happy (Dzhidaryan, 2013). Michael Argyle notes that while research often focuses on identifying the sources of happiness, the concept itself remains undertheorized, and a comprehensive theory of happiness is still lacking (Argyle, 2003). When it comes to children, there is a notable discrepancy between adult and child understandings of well-being (Titarenko & Klepach, 2016), highlighting the need for child-centered theoretical frameworks and research methodologies (Bayanova & Mustafin, 2013). Given these considerations, exploring how children perceive the factors contributing to well-being – especially happiness and what brings them joy – is a timely and significant area of psychological and pedagogical inquiry.

Does higher family income lead to greater happiness for children? How do children define and measure happiness? The conceptual scope of "happiness," as influenced by age, gender, and cultural background, remains underexplored. Among Russian psychologists, A.L. Zhuravlev and A.V. Yurevich have attempted to define happiness, examining it within the context of life meaning, which they consider a central component of happiness (Zhuravlev & Yurevich, 2014). While these concepts are interdependent in adults, little is known about their relationship in children. The younger the child, the less likely these two constructs are to be linearly related.

Ed Diener and colleagues define happiness as a subjective state reflecting overall subjective well-being (Diener, 2000). From this perspective, happiness is not only equivalent to subjective well-being but represents its highest form (Dzhidaryan, 2013). It is often conceptualized as a unidimensional construct—essentially a balance between positive and negative affect, along with a person’s overall life satisfaction (Linley et al., 2009). Single-item measures of happiness are common in international research and have demonstrated validity across numerous studies (Abdel-Khalek, 2006).

However, another body of literature approaches happiness through its structure and content. Martin Seligman’s theory of flourishing identifies key elements of well-being: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (PERMA model) (Seligman, 2011). Similarly, Michael Argyle highlights factors such as positive attitude, life satisfaction, optimism, and high self-esteem as contributors to happiness (Argyle, 2003). Zhuravlev and Yurevich’s “Typical Structure of Happiness” includes dominant positive emotions and thoughts, optimism, a positive worldview, a sense of life meaning, harmony between personal and suprapersonal values, and overall life satisfaction (Zhuravlev & Yurevich, 2014). D.A. Leontiev proposes a two-level model of happiness: (1) deficiency happiness, reflecting the satisfaction of basic needs given material and social resources, and (2) existential (self-determined or idealistic) happiness, rooted in self-realization and the achievement of personal life goals (Leontiev, 2020). These goals are linked to core personality structures, including self-fulfillment strategies, lifestyle, and behavioral patterns.

Talcott Parsons conceptualizes happiness as part of a dyad: the Achievable – what individuals strive for within social norms and self-realization in social being – and the Predetermined – that which is inherent and defined by personal traits (Argyle, 2003). As evident, understanding happiness involves analyzing the fulfillment of both physical and existential needs (Kazantseva & Lipovaya, 2019), positioning happiness as both an individual and a social psychological phenomenon.

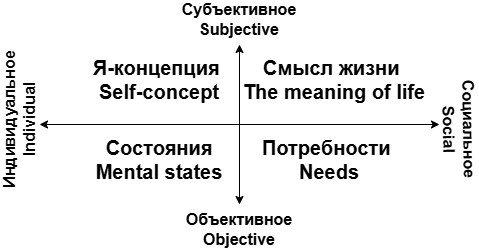

To conduct a substantive analysis, we draw on theoretical constructs from D.A. Leontiev and Talcott Parsons. By contrasting deficiency happiness and existential happiness from an ontological perspective, we establish the dichotomy of Subjective–Objective. Another dichotomy, Social–Individual, arises from the idea of human realization: within social being (emphasizing social norms) and individual being (prioritizing inherent personal traits). These dichotomies inform the representative fields of happiness used as the foundational category grid in our study (see Figure 1).

To explore children’s perceptions of happiness, we apply Abric’s concept of core and peripheral representations (Abric, 2001), identifying semantic cores within each representative field. These semantic cores are interpreted using Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotic triad: Object–Sign–Interpretant (Norris & Inglehart, 2011). In this framework, the representative fields are the objects, the semantic cores are the signs, and the expressed emotions are the interpretants. It is important to note that signs may carry emotional weight, as emotions are closely tied to motives, needs, values, and goals.

Based on this theoretical foundation, the study’s objectives are: (1) to identify basic perceptions of happiness among preschool and early elementary school children, and (2) to examine variations in these perceptions based on gender, age, cultural background, family structure, and expert assessment of the child’s “level of happiness,” derived from in-depth interviews and behavioral observations.

Materials and methods

We conducted individual video-recorded interviews lasting 20–30 minutes on average. After initial processing, the data were thematically categorized. The resulting classification was summarized in a table detailing each child’s responses across categories such as family, self-image, and emotions. Sampling criteria ensured categories were exhaustive, mutually exclusive, consistent, and relevant.

Thematic analysis employed text mining techniques, with words as the unit of analysis. Synonymous and cognate terms were generalized to identify the most frequently occurring words, which formed the semantic cores of children’s happiness perceptions. These cores were categorized using the author’s model of representative fields of happiness. Subsequently, the semantic cores were analyzed through Peirce’s triadic framework.

A comparative analysis of happiness perceptions across different child groups was conducted using statistical methods for qualitative data, including qualitative and quantitative content analysis, the Janis coefficient, Pearson’s chi-squared test, and expert assessment.

Sample characteristics: 120 participants (41 boys, 79 girls), aged 5–9 years (M = 6,6; SD = 1,43). The sample included 69 preschoolers and 51 elementary school children. Family structure: 100 from two-parent families, 20 from single-parent families (living with mother). Birth order: 41 only children, 41 firstborn, 35 secondborn, 3 thirdborn. Ethnicity: 73 Russian, 47 Tatar, with participants residing in the Republic of Tatarstan, Chuvash Republic, Mari El Republic, and Moscow.

Data were collected during individual creativity sessions involving paper crafts, during which children were interviewed using a semi-structured protocol developed by Yu.Yu. Panfilova. Questions included: What is happiness? Do you consider yourself happy? What makes you happy? What is your dream? What do you value most? What is most important in life? Do you believe in miracles? What was the best day of your life? Do you enjoy being a child? etc.

Results

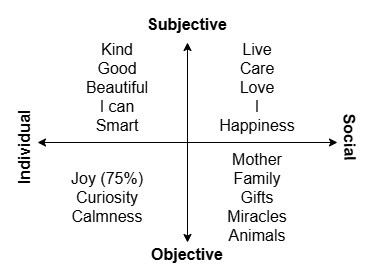

Semantic cores were identified based on occurrence in at least 50% of respondents.

Table 1. Analysis of semantic cores in children’s perceptions of happiness using Peirce’s semiotic triad

|

Object (representative) |

Signs (symptoms) |

Interpretante |

|

Self-concept |

Cheerful, kind, beautiful, smart, good, I can, I know |

Positive self-perception |

|

Meaning of life |

I will be, be, happiness, live, love |

Self-worth (“I for myself” vs. “I for others”) |

|

Satisfaction of needs |

Mother, love, parents, family, to be close |

Sense of belonging |

|

Mental states |

Joy, living well, (good, happy) life |

Optimism |

The central semantic core in children’s perceptions of happiness is joy. Joy is linked both to material aspects (e.g., LEGO, toys, money, tablets) and immaterial ones (e.g., parents being together, a mother’s kiss, helping people and animals). Notably, young children (especially preschoolers) often incorporate magical thinking: entering fairy tales, becoming birds, trees turning into marmalade, or being a princess. As Serge Moscovici observes, social representations shape how we perceive reality (Moscovici, 2000), and thus, fairy tales, miracles, and the sacred play a significant role in children’s conceptual worlds.

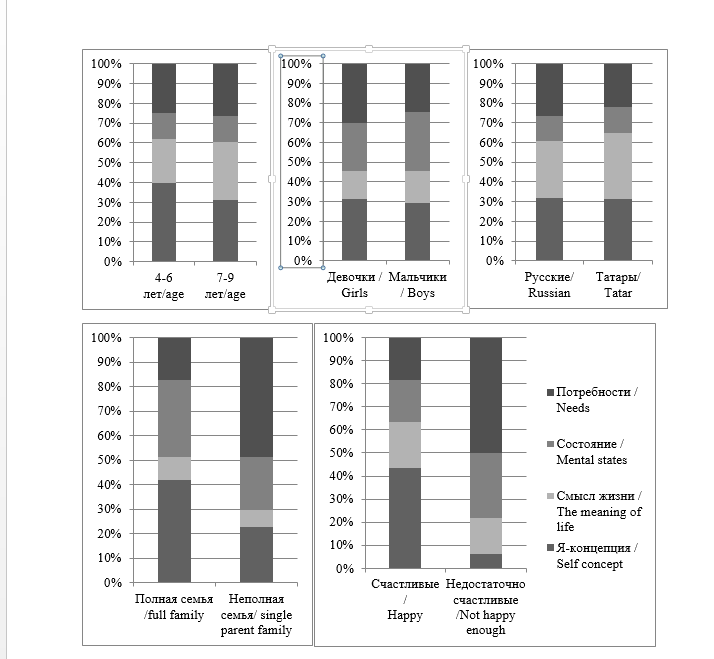

Age differences:

Preschoolers frequently mention “mother” as central to happiness, while elementary school children emphasize “family.” This shift may reflect growing autonomy and a broader understanding of familial bonds. Elementary school children associate happiness with “health” more than preschoolers do. Quantitative analysis revealed significant differences by age: older children show greater mindfulness and self-criticism (χ² = 12,045, p < 0,001 for self-traits; χ² = 5,055, p < 0,05 for needs). Cultural Differences: Tatar children frequently used gender-marked language, unlike Russian children (χ² = 10,1, p < 0,01). Gender Differences: Girls more often associate happiness with family; boys with their mother. Girls use the word “dad” significantly more than boys, suggesting stronger father-daughter bonds. No other significant gender differences were found.

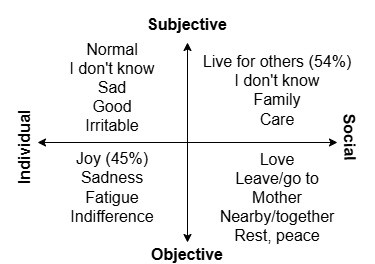

Family Structure and Birth Order: Children from single-parent families frequently use the word “together” when defining happiness (e.g., “Happiness is being together, close, and enjoying ourselves”). They rarely use the word “family,” instead referring to “mom” and “dad” separately – unlike children from two-parent families, who commonly mention “family.” Firstborn children are significantly more likely to mention “family” than later-born siblings, possibly due to assumed responsibilities. Children with siblings often mention “care,” “help,” and “play” (e.g., “Happiness is helping someone”). Level of Happiness: 14% of children responded “no” or hesitated when asked if they were happy. These children focused on others rather than themselves: “The meaning of life? I don’t know. My mom and dad had me, so I live.” “The meaning of life is to make everyone happy.” “To help my mom and dad.” Their responses reflect external determinants: “It’s good when I don’t have to go to hobby groups,” “It’s good when I don’t have school today.” In contrast, “happy” children used positive self-descriptors (beautiful, smart, kind, strong), while “not-so-happy” children used emotionally neutral terms (normal, simple, ordinary, so-so). Thus, children reporting lower happiness show deficient self-determination—low self-worth and a dominant “I exist for others” orientation (fig. 1).

Using the Janis coefficient, we analyzed emotional valence across representative fields. It is given as a 100% stacked column chart. The Janis coefficient allowed us to develop the semantic arrangement of the representative field of happiness for different groups of children. The arrangement is given as a 100% stacked column chart (Fig. 2).

Two types of semantic organization emerged: Balanced type and Need-oriented type. Balanced type found in children from favorable developmental contexts, with equilibrium across subjective/objective and individual/social domains. Need-oriented type: Characterized by an overemphasis on need satisfaction, especially in children from single-parent families or those with low happiness. Children from two-parent families show stronger individual-sector dominance, possibly due to family-centered parenting. As children age, mindfulness increases, and meaning-making may be replaced by internalized family values. The most vulnerable areas for “not-so-happy” children are self-concept (χ² = 65,349, p < 0,001) and meaning of life (χ² = 33,861, p < 0,001)—domains of existential happiness (Leontiev). Children from single-parent families also show weaker self-concept (χ² = 25,376, p < 0,001). Deficiencies in personal meaning and self-attitude lead to an over-reliance on material and emotional needs, risking a “materialization” of happiness and stagnation in objectification.

Discussion

Our findings align with Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), which distinguishes between intrinsic (autonomy, competence, relatedness) and extrinsic (wealth, fame, appearance) goals. Psychological well-being is enhanced by intrinsic goals but undermined by extrinsic ones (Olcar, Rijavec, & Ljubin Golub, 2019). Our study reveals a compensatory mechanism: children with weak internal resources overemphasize external needs – a pseudo-compensation rather than genuine balance.

Bradshaw et al. (2022) confirm that intrinsic goal pursuit correlates with well-being. The balance between individualization and integration – harmonizing “life for oneself” and “life for others” – is crucial for children’s happiness (Deeva, 2022; Bruk & Ignatzheva, 2021).

Our model of representative fields resonates with S.V. Molchanov’s types of psychological well-being in adolescents: balanced, ego-centered, and fortunate (Molchanov, Almazova, & Poskrebysheva, 2019). It also aligns with empirical findings: family and friends are central to children’s happiness (Bruk & Ignatzheva, 2021), and single-parent family children report lower happiness due to reduced emotional support (Yakovleva & Makarova, 2015). Our data confirm that these children less frequently associate “family” with joy.

The weak internal self-determination in “not-so-happy” children echoes Bruk and Ignatzheva’s (2021) findings on the need for balance between inner and outer worlds. In contrast, Belinskaya and Shaekhov (2023) suggest psychological adaptation and resilience may not always correlate with well-being – a nuance worth exploring further.

Conclusions

This in-depth interview study reveals the content and key determinants – socio-psychological and individual – of children’s happiness perceptions. By integrating Leontiev’s two-level happiness model and Parsons’ dichotomous framework, we developed a model of representative fields of happiness encompassing four domains: self-concept, meaning of life, satisfaction of needs, and mental states.

Key conclusions:

- For young children, happiness is emotionally grounded in self-worth (“I for myself”), positive self-perception, belonging, and optimism.

- In favorable developmental conditions, children exhibit a balanced semantic organization across subjective/objective and individual/social domains. With age, children become more reflective and critical—a shift evident in the transition from preschool to elementary school.

- Children from single-parent families and those with low happiness levels show imbalanced happiness fields, overemphasizing emotional bonds and material needs. The fewer positive self-traits a child reports, the more their happiness depends on need satisfaction.

As happiness perception is central to children’s understanding of social reality, analyzing it through representative fields allows us to identify deficiencies or overemphases in specific domains. These insights can inform psychological and educational practices aimed at fostering a “happy childhood” and preventing socio-psychological maladaptation.

Limitations. The study’s sample is uneven in size and limited in age range. Future research should include longitudinal designs to track the evolution of happiness perceptions and explore risks such as hedonism, addictive behaviors, and involvement in destructive groups. While qualitative methods do not require representativeness, future studies should expand the model to other age groups. Additionally, participation was limited to children whose parents consented.