INTRODUCTION

The image of Africa in the Polish media and public opinion of the Poles does not seem to differ significantly from the well-known and at the same time negative stereotype perpetuated in the perception of other European nations. Many contemporary researchers as well as journalists dealing with Africa's issues draw attention to the media's negative role in creating its image. French journalist and publicist Christian d'Alayer, the author of the book “Media crime against Africa. Are all Africans a nobody?”, is one of the more radical representatives of views on the role of the media in shaping social perception about Africa [d’Alayer, 2004]. In his opinion, the problem with its negative image is associated with the “afro-scepticism” in the field of investments aimed at increasing development and social progress. In further considerations, he claims that assigning only the negative traits described by AIDS, war, poverty and disease to “the Black Land”, is harmful and inadequate to reality. However, according to Radoslaw Sajna, the negative image of Africa in the media is the result of the inability to build its own image. The first reason for this is the backwardness in the field of telecommunications and information industry [Sajna, 2011, p. 438], while the second one refers to the limitation of media freedom in African countries [Sajna, 2011, p. 440]. The undis- putable fact is that the media have a huge

impact on shaping attitudes and opinions about regions and countries, while there is almost always a growing demand for a negative rather than positive message [11, p. 230—236]. Given these two factors, the conclusion is that if Africa does not “declare war” to Western media and does not take care of its own promotion, its image will never change, since the media has long ago “scented” the interest in the fact that “civilised” man is showing increasing interest in all kinds of social pathologies rather than beauty and good. Therefore, one might risk putting forward the thesis about the birth of a new type of cultural circles interested in the so-called “culture of death”, evil and violence, promoted by the media.

It should be emphasised that the study of factors shaping the image of Africa and its inhabitants in the opinion of the Poles is burdened with many difficulties. Three main premises testify to them. The first one is an anachronistic and partially obsolete image of Africa identified not only with wild nature but marked by the stigma of poverty, slavery and tribal conflicts, as well as shrouded in mysticism of unknown history. The second one is related to the migration crisis in Europe, which shaped the subjective and distorted image of a refugee and immigrant, describing him not as a person harmed by victimisation, but as a threat to the existing social order. Such an image of an African as “other”, “foreign” and even “worse” is vastly simplified and has quali

fying features encoded in the minds of not only the Poles but also most Europeans.

Not only have generalisations describing the Africans based on negative descriptors, especially in the face of the migration crisis, become a cause of panic among the Europeans, but they also set clear cultural and social boundaries between the Africans and representatives of Western civilisation. It should be noted that treating the Africans exclusively from the immigrant and refugee perspective also limits the field of analysis to part of the population of Africa, which further deepens the false image of its inhabitants. The third premise refers to educational issues centred around the low level of cultural competence of the Poles on Africa. All three premises have a common denominator. It is a negative stereotype, the strength of which is so great that the sight of a man with dark complexion in Poland almost always arouses “strange” emotions, which M. Z^bek devoted much attention to [Ząbek, 2006].

Among the publications referring to the image of Africa in the Polish media and social perception, noteworthy is Maciej Z^bek's book entitled “White and black. Attitudes of the Poles towards Africa and the Africans” that describes holistically the issues of shaping the image of Africa in Poland. The author presents a retrospective context of Polish-African relations, Arab stereotypes in the perception of the Poles as well as their attitudes over the last 20 years [Ząbek, 2006]. This author's article entitled “Continuity and Changes in the Polish Images of Africa in the European Context” constitutes the synthesis of reflections on Africa in the perception of the Poles [28]. The article by Katarzyna Andrzejczak, entitled “The Image of Sub-Saharan Africa in the Polish Press”, the essence of which is the description of the specificity of this part of the continent and its inhabitants as well

as the analysis of factors shaping the image of an African in Poland, is worth noting as well [Andrzejczak, 2014]. Previously cited Radoslaw Sajna published interesting conclusions about the influence of the media on shaping the image of Africa in the article entitled “Africa as a Victim and Beneficiary of Media Globalisation and Communication” [Study in Poland]. The article “Immigrants from Africa in Poland. A Contribution to the Analysis of Blocking factors, their inflow and integration” by Marta Danecka and Emilia Jaroszewska is of significant value among the publications referring to the Poles' perception of Africa and the Africans. The authors focused on extremely important issues relating to cultural and social barriers to the integration of African immigrants in Poland [Danecka, 2013]. The analysis of secondary data (desk research) was based on a whole range of research reports on the attitudes of the Poles to other nationalities, the impact of the media on shaping their perceptions about the Africans, as well as their attitude towards immigrants and refugees.

1. AFRICA AND THE AFRICANS IN THE OPINION OF THE POLES

The analysis of Africa and its citizens in the perception of the Poles imposes the need to look at it from the perspective of constant stereotypes created and consolidated not only by the media and pop culture, but also the world of sport and, importantly, from the perspective of cultural diversity and national identity of the Africans. The first issue regarding stereotypes requires their analysis based on positive and negative descriptive relationships or features that have been “coded” in the minds of the Poles under the influence of objective and subjective media stimuli and relatively rare contacts. The review of the

literature describing the retrospective relations of the Poles with African nationals allows the conclusion that in the Polish society, the stereotype of an African did not have an extremely negative context, but it rather expressed an ambivalent attitude. According to M. Z^bek, in the most general way it can be included in the words: “I like Negroes, but I do not value them” [Ząbek, 2006, p. 93]. This “soft” cognitive dichotomy allows the thesis that the historical stereotype of an African in the perception of the Poles was not burdened with the stigma of social distance, racism, intolerance or national chauvinism, but it expressed a kind of scepticism. It is also burdened with over-generalisation, which does not take account of the cultural specificity of Africa and the clear division into North and Sub-Saharan Africa. It was manifested mainly in the sphere of education, economy and culture. In the afore mentioned M. Z^bek's book [Ząbek, 2006], one can find numerous ridiculous stereotypes based not only on the lack of cultural competence, but which are the result of a deficit of mutual contacts resulting from the sparse African population in Poland. Expressions such as: “a wild with admixture of white blood” — as a reaction to a dark-skinned foreigner eating with a knife and a fork in restaurant, “horny” — as a stereotype of a sexually strong and half-wild male, “cute pickaninny” — as a reaction to a child in a pram, or “a rich Arab looking for a blonde” are typical reactions to the presence of African citizens among the Poles [27, p. 235—245].

Relatively rare contacts of the Poles with the Africans influenced such an understanding of Africa and its citizens until the transformation of the political system in 1990 [Wenzel, 2009, p. 8]. Few tourist trips, the work of Poles in Arab countries (mainly in Libya, Egypt, and even in South Africa) under contracts, or scholarships of students from Africa in Poland are the most visible manifestations of

contacts between Poles and Africans during the socialist period. During the building of democracy in Poland, the opening of borders, tourist traffic and the free market economy made the contacts much more frequent — although not common — than before. The stereotype of an African changed, setting a clear dividing line in the perception of the Poles about the inhabitants of the Arab states and the so-called “Black Africans.” At the same time, it began to take on an ethnic context in relation to immigrants from Africa, which means that it remained in connection with their place of origin. Katarzyna Andrzejczak indicates this source of stereotypes about sub-Saharan African people with the words: “a place of origin influences the social perception about immigrants, and thus entails implications concerning the way in which they will assimilate with the society. People rely on their own ideas, partially shaped unconsciously, and attribute the resulting qualities to groups”. [Andrzejczak, 2014, p. 203]. The creation of a stereotype takes place due to the asymmetry of strength and social position between a migration group and an indigenous group [Goodwin, 1998]. The results of the research presented in the article by M. Danecka and E. Jaroszewska [Danecka, 2013] proved not only the existence of such a mechanism in shaping the stereotype of the “Black African” in Poland, but also the presence of significant barriers to their elimination and cultural assimilation. One of them is the relational barrier resulting from the poor attitude of the Polish society towards the citizens of African countries. The second one refers to a cultural barrier that shows too big cultural differences between the Poles and the Africans. The third one should include the communication barrier arising from poor (or lack of) language skills as well as differences in the sphere of non-verbal communication [Danecka, 2013, p. 161]. Barriers in non-verbal communication stem from differences in semiotics based not only on the

importance of proxemics — communication distance, oculesics — eye contact, haptics — touch, kinesics — body language, as well as vocalisation and para-language.

1.1. Population of the Africans in Poland

According to the data of the Polish Office for Foreigners of 2018, 5808 citizens

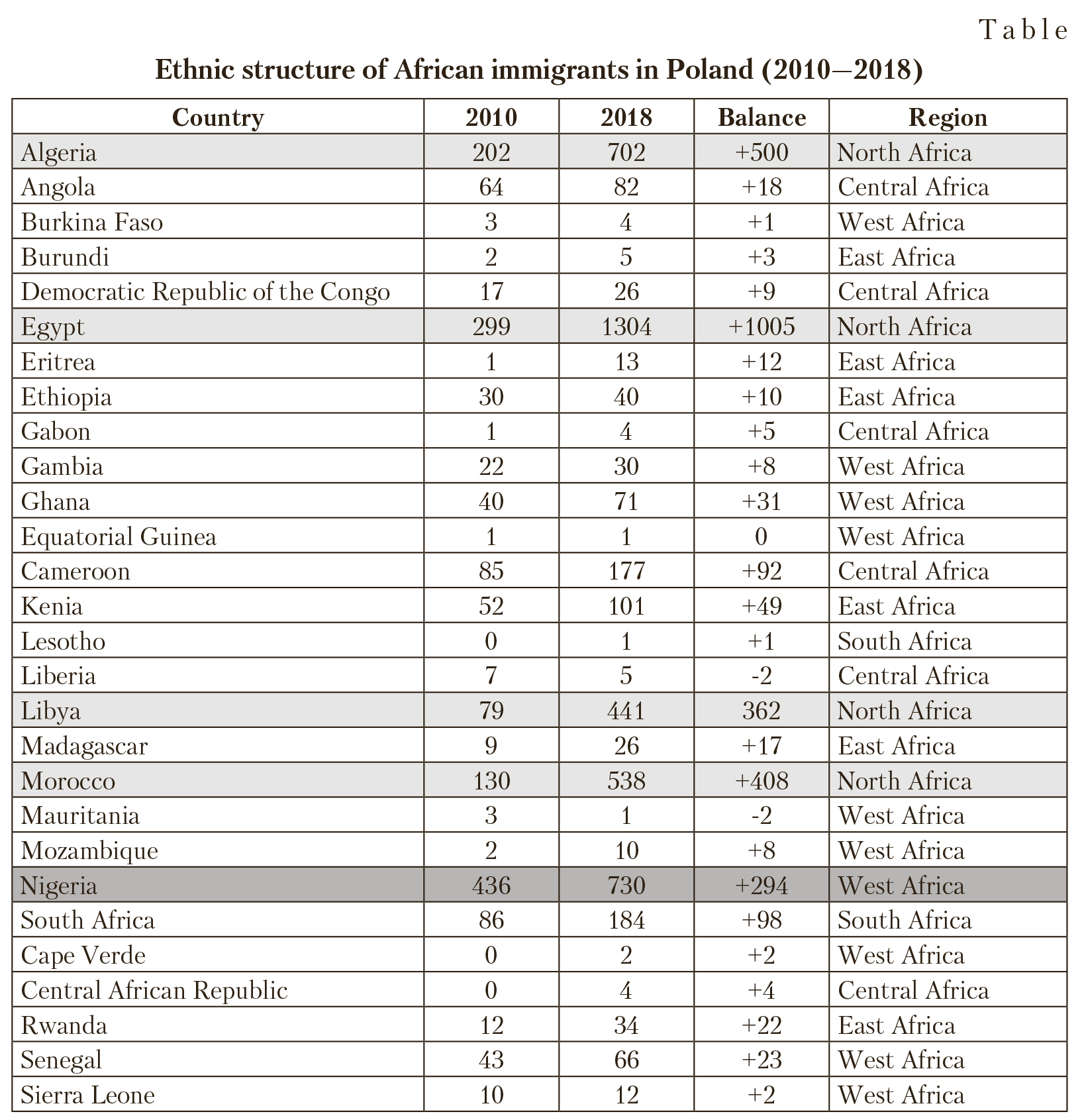

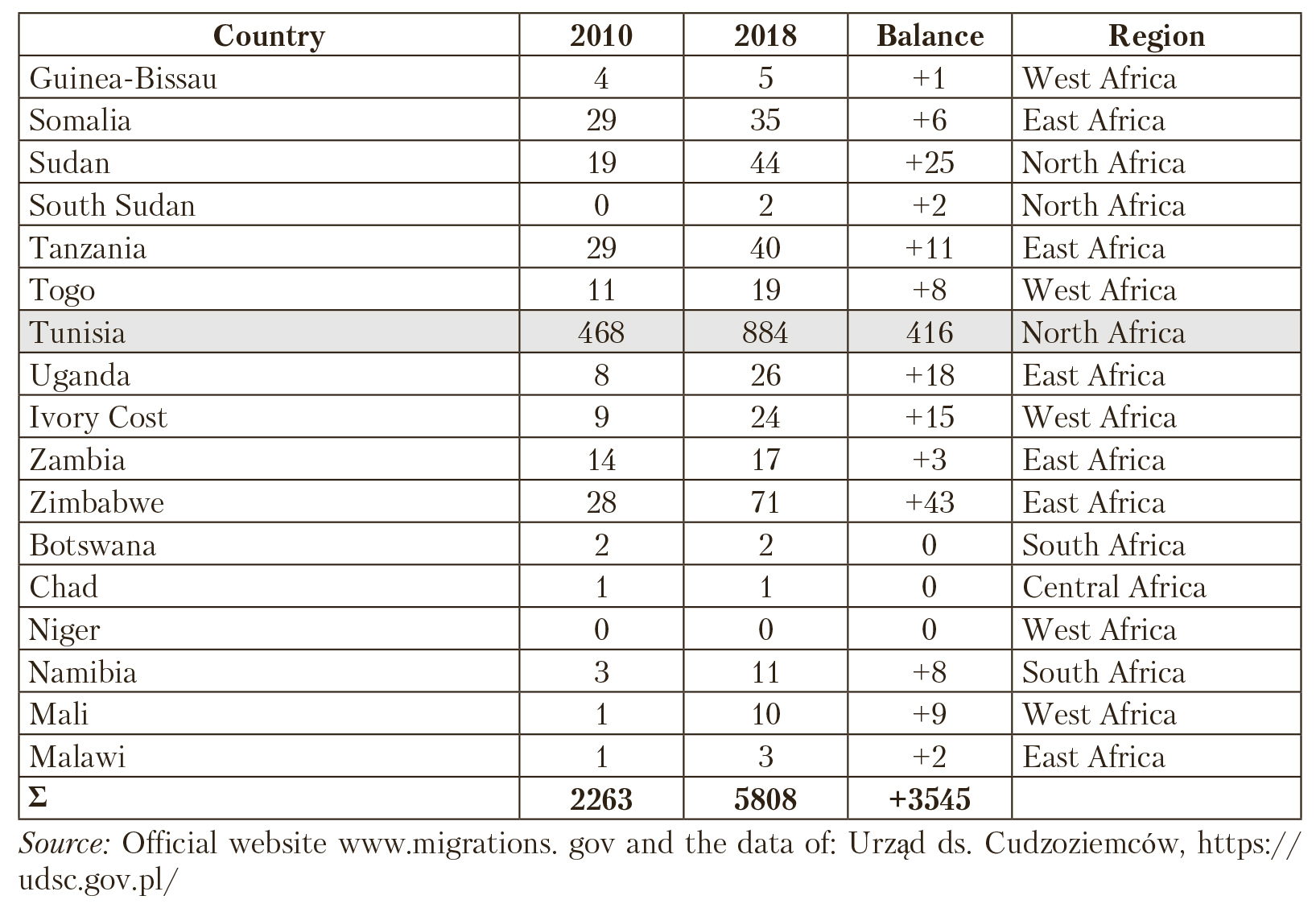

of African countries are legally present or reside in Poland. They represent 45 out of 54 African countries and constitute about 5% of all foreigners in Poland, of which only 3% are representatives of Sub-Saharan Africa [Wainaina]. Table presents the ethnic structure and population of immigrants from Africa in Poland in the years 2010 and 2018.

The analysis of the data presented in Table depicts a clear population diversification between immigrants from North and SubSaharan Africa. In 2010, as many as 52% — 1178 people of all 2263 Africans represented North Africa. In the discussed year, the largest group were the Tunisians — 468 people and the Egyptians — 299 people. An interesting observation concerns the Nigerians representing a group of Sub-Saharan African countries — 1,085 people. Their population of 436 in 2010 constituted as much as 40% of all citizens of the “Black Africa” states. In 2012, the main country of origin of immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa was also Nigeria, whose citizens made up more than one third of all immigrants from this region, followed by Cameroon, while Kenya and Angola held the third position [Danecka, 2013, p. 158]. A clear change in the population of immigrants from Africa in Poland took place in 2017 and 2018. The data from the Office for Foreigners show that in eight years it has increased by 3545 people, including 2716 ones among the nationalities representing North Africa — an increase from 52% to 68%, which is justified by migrations resulting from the revolution in the Arab states and geographic proximity with Europe. The peak was recorded among the Egyptians — by 1005 people and Algerians — by 500 people. It should be stressed that immigrants from Africa most often settle in the Mazowieckie Voivodship — 1830, in the Malopolskie Voivodship — 456, and in the Dolnosl^skie Voivodship — 420 people (Urz^d ds. Cudzoziemcow, 2018). The data presented come from official sources, however, one should bear in mind the illegal immigration from Africa, which, according to various sources (such as the Border Guard and the Police), can be shaped even at the level of 2000 people.

1.2. Students from Africa in Poland — cultural and relational barriers

Apart from immigrants, an increase in the number of students from Africa is noticeable in Poland. In the 2017/2018 academic year 1373 students from 37 African countries undertook studies in Poland, of which the largest group are Cameroon (482 people) and Nigeria (218 people) nationals. They constitute a very low percentage (2,1%) of the number of 65096 foreign students studying in Poland [Szymańska, 2014].

The increase in the population of African students did not significantly change the attitudes of the Poles towards them. The attitudes should be classified as ambivalent, and their positive (declared) character is rather apparent than real. It is difficult to talk about any form of cultural conflict or even passive antagonism, which is noticeable in the relations of the Poles with the immigrant background, nonetheless the Poles' reluctance towards African nationalities is perceptible. Apparent coexistence is evident in the mutual relations of students, which is, however, in many cases burdened with social distance on the part of the Poles. The Africans point out in their opinions the different character of the relationships, which indicates that they have been negative for years. The research conducted in 1990 at the University of Warsaw proved that 100% of the surveyed students from Africa suffered from physical and verbal violence on the part of the Poles, and relations with the Poles are among the worst (compared to other nationalities). The surveys of 2010 confirmed this trend with the increased percentage of 27% of students assessing relations with the Poles as positive [2, p. 165]. In turn, the report on the qualitative research conducted by the Department of Migration and Ethnic Relations of the University of Warsaw in 2013 reveals a great many interesting aspects of life of students from African countries. In addition to the assessment of living conditions, the level of studies and communication barriers, it presents social and cultural problems in relations with the Poles [Jaroszewska, 2015]. Although the research results do not reveal cases of aggression and personal inviolability on the part of the Poles, the Africans were convinced of their cool and closed attitude towards most nationalities studying at Polish universities. Here is a quote from the research: “I can say that I have not had any bad experiences with the Poles so far. But generally, I can say that Poles are suspicious of foreigners. (laughs) (...) They are not very open to foreigners (...) it is not easy to get closer to Polish students. They prefer being reserved (...) they prefer being locked up in their small groups” [10, p. 60].

Numerous accounts from the report direct attention to the limitations in mutual relations. Apart from reluctance, social distance, intolerance and simple ignorance, respondents of interviews indicate lack of or poor language competence on the part of the Poles. Here is one of the statements: “(...) we usually met in the kitchen (...) So they cooked for themselves, we for ourselves. And nobody said anything. (...) They have their parties and they do not invite us, we have ours. (...) They do not like us. Or they do not know English. More probably the latter.” [10, p. 61]. Other interviews demonstrate positive but sporadic relations with the Poles, which are manifested in the will to help, joint events or even visits at Polish homes. However, it should be highlighted that the key factor hampering the integration between African and Polish students is the lack of cultural competence on both sides. The Africans know about the Poles as much as they read in the press and foreign books — that is not much, and the Poles derive knowledge from the media and stereotypes rooted in their consciousness. It should be noted that due to the increase in the number of students from Africa, especially at the University of Warsaw and the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, the social distance has been reduced and the interest in African culture is growing not only among academic teachers, but also students. The picture of an African in the perception of a Polish student is also changing. The stigma of “Dirty Arab” and “Black” has almost completely disappeared, and the students began to be looked at through the prism of national identity and cultural difference. This is a positive herald of a new era in the relations of the Poles with “Africa”, which with the growing population of students from Africa in Poland can shape a more real and stereotype free image.

2. IMMIGRANTS FROM AFRICA IN THE PERCEPTION

In opinion polls conducted not only in the period of the beginnings of democracy in Poland, but also after the year 2000, there is a lack of data on the attitudes of the Poles towards specific African nationalities. Nonetheless, generalisations such as “Arab” and “Black” can be found in the reports. It was only in the report by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS) from 2011 that references to the Libyans and the Egyptians appeared [2, p. 164]. The report entitled “Opinion Polls on the Integration of African Nationals in Poland” published in 2015 is one of the most important sources of data on the attitudes of the Poles to the Africans. Research results indicate that citizens of African countries face various integration barriers, including verbal and sporadically physical aggression, paying attention to race and lack of language competences. The Africans mention the following sources of aggression: ignorance, lack of knowledge, racism, nationalism and ill-considered patriotism of the Poles, disrespectfulness to others, jealousy for women, and stereotypes [7, p. 13—14]. They are convinced that one can gain education and professional experience in Poland and they appreciate Polish cuisine, hospitality and honesty, as well as the beauty of Poland and its economic development. They definitely dislike the Polish climate and complain about high prices and low earnings. Polish defeatism, aggression after drinking alcohol, intolerance and coldness against “foreigners” is unacceptable to them. However, they love Polish women but, as they say: “Very beautiful, but not for a wife. They want to control a man too much. Polish women want to have more to say than men, they like to rule”. The Poles' indifference to racism also affects the negative image in the opinion of citizens of African countries [4, p. 15]. In addition to the issues raised, the report also reveals the low level — just like among students — of the Poles' knowledge about Africa, which comes mostly from the Internet. This source was indicated by as many as 77% of the respondents (1000 people aged 15—75).

‘The media construction of reality, depending on the level of knowledge and the audience emotional aptitudes, may favour structuring, standardisation, universalisa- tion, and even trivialisation of the image of the world functioning in the social consciousness' [19, p. 14]. Analysing the media coverage, one should be aware of three aspects of intercultural communication: it concerns a distant culture — in the sense of a distance, both geographical and cultural, the audience expectations affect the coverage, and editors and journalists know this and provide the desired ‘product'.

The media image of Africa, more than those of other countries/continents, has been deformed and distorted. The actual image is distorted when forming and reading the content of the message. The reasons for this can be sought in the mediatisation of everyday life, involving the imaging of reality in the media coverage, which then affects the reality perceived by the audience [19, p. 12]. Recently, mediatisation of everyday life has concerned almost all aspects of our lives. It is important as the media play a role of an informational, orientational, educational, and advisory source, and they stimulate social activities as well. The media also constitute a main area where political activities are criticised and the legal authorities are controlled. In other words, they generate and form messages adopted by the public as their own [19, p. 12]. For the purpose of this article it is important that the media play a role as a transmitter and a modulator of norms, values and cultural traditions.

The analysis of the way medial representations of Africans are presented in the media may provide us with some knowledge about the symbolic conditions of the relationship between the dominant culture and a foreign culture, in this case, it can generally be regarded as ‘African'. Public perception of the continent, country, nation, culture, ethnic group or religion is strongly determined by the quality of media coverage of the subject, just as the status of Africa as a continent/country and the Africans is created based on their media image. Through the media coverage and personages or media events created in it, the media affect the formation and, on the other hand, dissemination of the image of Africa and its people or a possible change in it. Therefore, constant monitoring of the media to identify information gaps and deformation of the image presented in them is very important.

The topics related to Africa and its people very rarely appear in main editions of the news. If something appears in the media ‘headlines', it is related to a dramatic event with thousands of victims or other events with negative social impact. In 2010, a survey how to portray Africa was conducted. These studies were commissioned by the Foundation ‘Africa Another Way'. The results of the research show that the media and reportages (there was an often cited Wojciech Cejrowski's programme ‘Barefoot through the world' and Martyna Wojciechowska's ‘A woman on the edge of the world') are one of the main sources of acquiring knowledge about Africa for an average Pole [Średziński, 2010].

The analysis of hate speech and its sources revealed that the negative image of Africa has its main source in the media coverage. In the case of reportages and relations from African countries in the media coverage ‘dead-kilometre law' is functioning. The easiest way to explain the above may be as follows: the farther — not only geographically, but also culturally — a given region of the world is located, the less interest is shown by the audience; thus, there is a need of an increasingly dramatic, bloody message so to ensure the attention of readers/ viewers. Only negative broadcast is successful, hence information about African art or African Nobel prize winner not fulfilling the above law, rarely appears in the press. Wojciech Jagielski's articles concerning, among others, South African Nobel prize winner Desmond Tutu [Jagielski; Jagielski, a] or Szymon Holownia's articles about a positive development of African countries [Hołownia, 2011] were exceptions in the observed period 2010—2011.

The negative image of Africa is frequently supported by humanitarian organisations. In the Polish context the language of humanitarian aid organisations happens to be a confirmation of the thesis that there can only be difficult situation in Africa, and a negative image of poverty and hunger is to cause a greater willingness to help. It is worth noting here that Africa, especially in the context of humanitarian aid, is perceived as a country, not as a continent. Adam Leszczynski's articles that appeared in the ‘Gazeta Wyborcza' supported the deepening of the distorted image of Africa as a country constantly demanding help in the fight against poverty and hunger [Leszczyński; Leszczyński, a]. The messages about the aid were provided mostly by Polish Humanitarian Organisation and UNICEF. Another point of view is presented in Dariusz Rosiak's text published e.g. in ‘Rzeczpospolita', in which the author tries to answer the question why the humanitarian aid is disastrous for Africa and why it should not be helped [Leszczyński, a; Rosiak]. It should be noted, however, that this was a unique text in its meaning.

A separate but at the same time dominant image of Africa is its image as a con- tinent/country of the sunset, full of wildlife and endless space. The wildlife was a respondents' association with Africa in the research. The savagery included both animals and humans. Africa was regarded as the most dangerous place on Earth. In the ‘Nowiny' one could find out that African countries are engulfed by continuous, endless conflicts and they do not belong to the places for spending holidays [Urząd].

The image represented by the Polish mass media is a part of the narrative disseminated by the Western media. Therefore, the Africans issued a critique of the media coverage concerning their continent presented in the media, mostly Western ones. The text about the Western media description of Africa published in 2005 by a Kenyan journalist and researcher Binya- vang Wainaina is the best illustration of the above. He comments the Western press with irony, mockingly pointing out stereotypes that are used by journalists writing about events in African countries:

“Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book, or in it, unless that African has won the Nobel Prize. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these. If you must include an African, make sure you get one in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress (...). In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don't get bogged down with precise descriptions. Africa is big: fifty-four countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book. The continent is full of deserts, jungles, highlands, savannahs and many other things, but your reader doesn't care about all that, so keep your descriptions romantic and evocative and unparticular” [Wainaina, 2014].

The report of the media monitoring was repeated in 2015 in the framework of public opinion research into the situation of the Africans in Poland [Dudziński, 2015]. It was a special time, especially at the end of the year when the problem of refugees began to be widely disseminated in Europe. Europe has ceased to be an anchor of stability and prosperity for the Poles. Since the beginning of 2015, the media in Poland has primarily reported about boats with thousands of refugees from North Africa, deepening poverty, and terror of Islamic fundamentalists. Has the perception of Africa and the Africans changed due to it?

The fact that the media coverage concerning Africa and its people virtually unchanged in the period 2010—2015 can also be applied to the already fixed image of the continent. It should also be remembered that by analysing the relationships between political culture and the media in relation to public discourse, the media often serve to maintaining or even strengthening the status quo of our culture. Disseminated images must enter a valid cultural context and provide appropriate content. While the media strengthen emerging and existing trends and cultural images.

Separately, the so called ‘logic of the media' should be emphasised [19, p. 19]. It is a developed by the editorial team logic of selection and presentation of information, which is based on journalists' attentiveness to the presented topic, and, on the other hand, on expectations of the audience. The system, under the pressure of extreme expectations, causes a whole range of deformations of the image of reality presented by the media. In addition, it should be noted that the subject matter and its presentation by the media in Poland is dependent on the Western media. The aforementioned Kenyan writer and journalist Binyavang Wainaina tells in his book ‘One Day I Will Write About This Place' how once he was called by a Dutchman from an EU humanitarian centre seeking an author who would write about African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) in Sudan. He argues: ‘we want a proper... African writer to write a book about what he sees. You know, Literature. We will publish it and pay for everything. You will go with a photographer. It will be something different. Powerful. Literature and photographs' [Wenzel, 2009, p. 103]. Wainaina took up the challenge. Eventually, the book was rejected, since plenty of the issues raised in it were inconsistent with the EU policy. ‘The EU is very jittery about the book. They say that the EU policy says there is only one Sudan, but history says South Sudan!!! (.) Many things are not in line with the EU policy' [Wenzel, 2009, p. 104]. The issue of media policy is a subject that deserves a separate study. Here it serves just as a draft of building one of the stages of a stereotype concerning African continent.

CONCLUSION

Africa and its inhabitants in the perception of the Poles and the media coverage are the subject of research, which, although it has been popular with scholars and research centres for years, still leaves great research scope in the field of sociology, cultural anthropology and ethnography. The increasing number of African citizens in Poland in different categories of stay imposes the need to undertake activities aimed at increasing cultural competence on Africa among the Poles, as well as building correct relations on the path of intercultural communication. Undoubtedly, such activities include education, not only traditional — school, but also, and above all, media, whose aim would be to shape a real, not distorted, image of poverty, backwardness, refugees, diseases and pathology that is well-known to the mass media in Europe, as well as wars and terrorism. Obviously, this is not about creating an artificial and forced image, but about the truth about the causes of the problems raised. Above all, however, it is about the decency that Europe and the Europeans owe Africa for the past and present, in order to learn how to live among different things and to co-exist in a multicultural community.