Introduction

It is a known fact that over the last 20 years, Russia has been undergoing an active transition to a new paradigm of educational outcomes, founded upon the competence-based approach. This approach assumes that educational outcomes should be expressed not as knowledge, skills and abilities (KSA), but as a set of motivational, value-centric cognitive components, or competencies [Zimnyaya, 2009]. The integrative educational outcomes achieved through this approach should ensure the young professional's competence. According to the Strategy for Modernising General Education Content, developed in 2001, the concept of competence is broader than the concept of knowledge or ability or skill. In fact, it encompasses all of its concepts, while at the same time obviously not amounting to their simple additive sum. Conceptually, it belongs to a different category. The concept of competence includes not only cognitive components and operational technological components, but also motivational, ethical, social, and behavioural components [Strategiya modernizatsii soderzhaniya, 2001, p. 16]. It should be noted that one of the objectives of implementing the competence-based approach at the higher education level is to ensure that graduates become involved in their professional field as successfully as possible.

The competencies that students should acquire in the education process are laid down in the Federal State Educational Standards (hereafter FSES) for each level of education. The approach to FSES content was established in 2007 and has not changed significantly since then. The adoption of the new Federal Law on Education in the Russian Federation in 2012 regulated the use of the FSES. According to this law, the quality of education is determined by the curricula's FSES compliance. At the same time, another criterion for the quality of education is provided: "correspondence to the needs of the student". However, this is not directly reflected in the law [Knyaginina, 2020].

According to the current FSES concept, this criterion is defined as a set of compulsory requirements that are used to assess the both the student's training and the activities of the educational organisation. However, the FSES sets the rules for curriculum structure without touching on the details of educational content.

A review by N. V. Knyaginina points out that most of the domestic researchers' publications related to the FSES "have no clear scientific relevance and limited practical value" [Knyaginina, 2021]. Most articles deal with the differences between the different FSES generations, mainly aiming to support the work of methodologists. Another group of articles reflects practical experience in arranging a FSES-compliant education process in different fields [Knyaginina, 2021]. For the purposes of this article, it is important to mention several works that have focused specifically on critiquing some aspects of the FSES concept.

- B.Golub and co-authors have written an article on competencies in higher education, where they point out the problems with assessing the student competencies that are listed in the FSES. As the main issue, the author cites the overly generalised nature of competence descriptions and suggest options for making them more specific. The approach boils down to identifying what can constitute educational outcomes from the wording of the general professional competence descriptions. This is then intended to serve as basis for identifying specifically knowledge-based educational outcomes: "knowledge-based outcomes should be formulated as indicator corresponding to a given content unit and the level of its mastery <...> the resulting statements should be considered as minimum requirements for the formation of the general competence in question" [Golub, 2013, p. 160]. Accordingly, education control is limited to the knowledge-based outcomes that were previously identified. For example, the general competence that is described as "refusal to tolerate corrupt behaviour, high level of legal awareness and legal culture" can be assessed only insofar as it concerns what the student has learned, i. e. "the student can explain the social meaning of law and to identify signs of corrupt behaviour in a given situation" [Golub, 2013, p. 170]. In the same paper, the authors present the results of an expert analysis of 200 higher education standards (FSES) in different areas. They note that the concept of competencies is essentially substituted by academic outcomes (knowledge, skills and abilities) and that some competencies (like tolerance, civic stance etc.) cannot be measured [Golub, 2013; Knyaginina, 2021]. V. S. Senashenko [Senashenko, 2008] also points to the lack of integrity in the FSES being developed. V. S. Lazarev holds a similar point of view regarding general education and suggests that the replacement of KSA with competencies has been surface-level [Lazarev, 2015]. We are inclined to agree the above comments, with one caveat: in the above examples of the specific nature of educational outcomes, the concept of "aptitude" is also eliminated.

Noting the shortcomings of the FSES, T. A. Pereskokova and V. P. Solovyov highlight the lack of a student-centric approach, typical of the Bologna Process, in domestic educational standards. The FSES mainly contains requirements for the control and organisation of the educational process [Pereskokova, 2019; Solov'ev, 2016]. At the same time, the individual characteristics, interests and motivation of the students, i. e. the essentials of their subjectivity, are left out of the picture.

A very interesting comparison of educational standard concepts is given in the work of O. Kh. Miroshnikova. The author notes that the FSES system currently used in Russia correlates with the US idea of educational standards, wherein all students are expected to achieve the same results. It is interesting to note that the US has not joined the Bologna Process and uses its own system of higher education. At the same time, the actual term "competence" in foreign education implies "a high degree of education individualisation and differentiation, which involves assessing how well the goals set by the student together with the educator have been achieved" [Knyaginina, 2021; Miroshnikova, 2015]. However, we must note that the issue of individualisation is one of the core issues in B. M. Teplov's discussion of aptitude, where the problem of individual differences is central [Teplov, 1985].

It should be noted that the authors of the works cited review the concept of the FSES as a whole, in relation to the entire education system. The present article, however, will examine select features of the FSES, in particular the competence-based approach, in relation to the acting profession. Mastering creative professions notably presupposes having aptitude in a particular field, such as music, painting, acting, etc. It is for this purpose that admission to art universities involves special creative tests designed to determine whether applicants do possess said aptitude. In addition, according to the FSES concept, graduates should acquire an identical, pre-approved set of competencies. However, the specifics of developing artistic aptitude, where compensatory mechanisms and the individual nature of the activity play an important role, remain a grey area.

A competence-based approach to actor training

Over the course of competence-based learning in higher education institutions, the content of the competencies to be mastered has changed considerably. The current FSES standards for higher education are in their third generation (3++). In this context, it is interesting to analyse the changes in the content of the FSES for the acting profession (specialist degree) from 2002 to 2021.

For this purpose, we analysed the parts of the FSES that record the requirements for a theatre graduate (acting competencies): FSES for 2002, 2010, 2017 and 2021.

The first thing worth noting is the significant differences in structure, content and wording between the 2002 educational standard and the FSES for 2010, 2017 and 2021. This is due to the fact that FSES 2002 was created during a period of transition, when the competence-based approach had not yet been fully implemented in Russian higher education. This educational standard contains the lowest number of requirements (10) for the graduate's professional qualifications compared to the later FSES. In comparison, the number of competencies to be formed by graduates in their field is 39 both in FSES 2010 and in FSES 2017. All the requirements specified in the 2002 standard are, however, of direct relevance to the acting profession. For instance, a graduate should "be fully capable of perceiving the world in artistic terms", possess "visual thinking", "know the methods of creating a fictional persona through acting, as required by the respective type of performing arts", "have the skills required for independently performing their role (part, number) according to the director's plan", "have well-developed, professional vocal skills", be proficient in "the art of speech as an aspect of the national cultural heritage", etc. [Gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi standart].

Starting from 2010, the FSES for acting, according to the general methodology of the FSES, has included three categories of competencies: general cultural competencies (renamed into "universal competencies" in 2021), general professional competencies, and professional competencies. The content of general cultural competencies is the same for all specialisations and requires the actor, as well as any other professional with higher education, to possess an aptitude for activities that are not directly related to their work but are evidently meant to reflect their overall education level, such as "navigating existential, life, and cultural values" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi]; "abstract thinking, analysis, synthesis" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi, b]; or "approaching problem situations critically and systemically and developing a strategy of action" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi, a]. In quantitative terms, we can note that the number of competencies at this level did not change in 2010, 2017 or 2021 and includes 10 units.

The content of the general professional competencies is also quite removed from the actual activities of professional actors. The FSES 2010 and 2017 outline 9 competencies in this group. They differ in several aspects and mostly describe what any person with higher education should know how to do: "scientifically organise their work, independently evaluate the results of their activities, master the skills of independent work, including scientific research, artistic and creative work" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi], "independently seek employment in the labour market, master economic evaluation methods for assessing their art projects and intellectual work" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi, b], "use special means and methods to achieve creative discoveries, individually or as part of a group" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi, b] etc.

Interestingly, FSES 2021 contains only 5 general professional competencies, which differ significantly in their content from the previous editions. On the one hand, there is an emphasis on the creative nature of the graduates' professional activity ("the aptitude <...> for comprehending a work of art in a broad cultural and historical context in connection with aesthetic ideas of a particular historical period"). On the other hand, the relationship between the actor and the government is outlined as well ("awareness of the contemporary cultural policy of the Russian Federation"). The aptitude for leadership and teaching in the arts and culture is listed as well.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the professional competencies that are directly relevant to the activities of a theatre school graduate. FSES 2010 and 2017 have the longest list of professional competencies, with about 20 descriptions that do not differ much between the two. These include the wording used in the 2002 standard, as well as new statements. On the whole, the list accounts for various aspects of an actor's professional work, including: readiness to create a fictional persona, ability to communicate with an audience, willingness to show creative initiative, aptitude for work in a creative team, various qualities related to speech, bodywork, the basics of musical literacy, singing and ensemble skills, and capacity for keeping in shape and maintaining the psychological and physical balance necessary for creative work.

It is important to emphasise that as of today, FSES 2021 does not contain a "professional competencies" section at all. In order to identify the necessary competencies while developing the curriculum, higher education institutions are expected to refer to the professional standards corresponding to the specialisations of their graduates, if such standards are available. In the absence of such professional standards, professional competencies are defined by universities themselves. There are currently two professional standards that can apply to the acting profession: "Teaching extracurriculars for children and adults" and "Vocational training, vocational education and further vocational education", both intended for teachers. This means that, when developing curricula and compiling a list of professional competences for their graduates, theatre schools are obligated to include competencies that comply the two aforementioned professional standards for teachers, as well as, at their discretion, any other professional competencies.

On the five curricula and actor competencies

Studies of the curricula designed at five major Russian theatre schools – Studio School of the MKhAT, B. Shchukin Theatre Institute, Yaroslavl State Theatre Institute, Russian Institute of Theatre Arts - GITIS, and the Higher Theatre School (Institute) named after M.S. Schepkin – have shown that the curriculum writers use the wording that was established in the previous editions of the FSES [Osnovnaya obrazovatel'naya programma; Osnovnaya obrazovatel'naya programma, a; Osnovnaya obrazovatel'naya programma, b; Osnovnaya obrazovatel'naya programma, a1]. However, it is worth noting that, compared to 2010 and 2017, the number of professional competencies on the 2021curricula has decreased from 21 to 7-11 (depending on the specific school).

We have analysed the content dynamics of professional competencies from 2010-2017 to 2021.

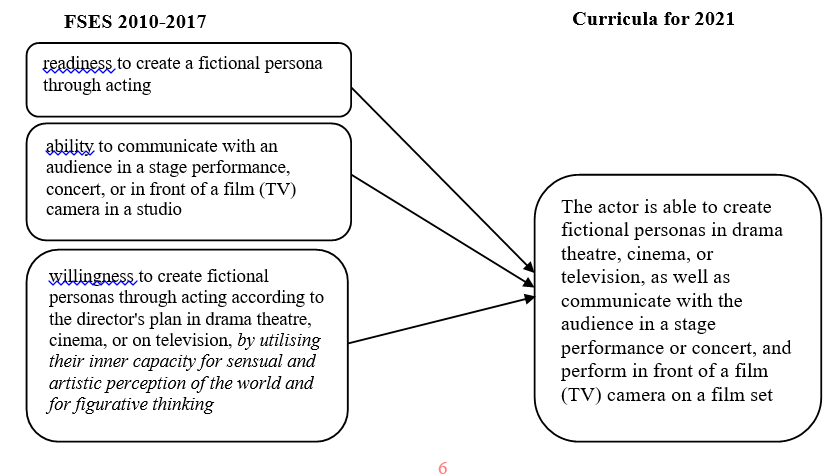

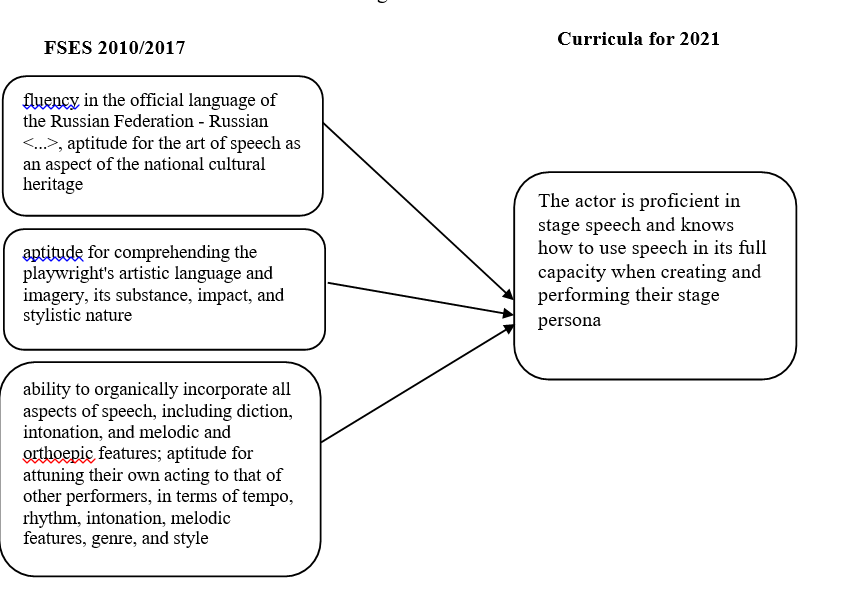

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the integration of competencies relevant to the actor's presentation of their fictional persona, as well as the various aspects of language use and stage speech. These competencies have undergone a number of changes.

While in the 2010-2017 standards, the character presentation competencies (see Figure 1) were formulated in some detail, in 2021, the three respective competencies were merged into one. This integration has led to the loss of an important component of the actor's stage presentation: developing the aptitude "for sensual and artistic perception of the world, for figurative thinking" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi; Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi, b], which was mentioned in the FSES of 2010 and 2017. In this context, it should be emphasised that the current educational curricula do not cover the development of the actor's thinking, or the development of certain artistic skills, whatsoever.

|

The actor is able to create fictional personas in drama theatre, cinema, or television, as well as communicate with the audience in a stage performance or concert, and perform in front of a film (TV) camera on a film set |

|

readiness to create a fictional persona through acting |

|

ability to communicate with an audience in a stage performance, concert, or in front of a film (TV) camera in a studio |

|

willingness to create fictional personas through acting according to the director's plan in drama theatre, cinema, or on television, by utilising their inner capacity for sensual and artistic perception of the world and for figurative thinking |

|

FSES 2010-2017 |

|

Curricula for 2021 |

Figure 1. Changes in the content of the competencies relevant to the actor's presentation of their stage character.

|

The actor is proficient in stage speech and knows how to use speech in its full capacity when creating and performing their stage persona |

|

fluency in the official language of the Russian Federation - Russian <...>, aptitude for the art of speech as an aspect of the national cultural heritage |

|

aptitude for comprehending the playwright's artistic language and imagery, its substance, impact, and stylistic nature |

|

ability to organically incorporate all aspects of speech, including diction, intonation, and melodic and orthoepic features; aptitude for attuning their own acting to that of other performers, in terms of tempo, rhythm, intonation, melodic features, genre, and style |

|

FSES 2010/2017 |

|

Curricula for 2021 |

Figure 2. Changes in the content of the actor's speech competencies.

With regard to competencies reflecting the students' mastery of different speech aspects, the most significant changes have taken place between 2010-2017 and 2021 (see Figure 2). Specifically, we no longer see the competence that calls for mastering the Russian language and the art of speech as part of the national heritage. Comprehension of the playwright's artistic language and imagery is also gone, as are the detailed descriptions of the various characteristics and functions of stage speech. Instead, the relevant competence is formulated in a rather short and utilitarian way. In this new wording, stage speech appears to be purely auxiliary and instrumental. One might assume that the brevity of the wording gives universities the necessary freedom to educate their students according to their own perceptions of the discipline, without forcing educators into a bureaucratic box. However, from our point of view, the cut content is extremely important for the training of future actors, since theatre schools traditionally teach stage speech as a discipline.

It should be noted that the tendency towards cutting the wording is also true of other professional competencies in stage movement, dance and musical disciplines. In general, this may make it easier to design educational curricula and meet the requirements of the FSES. But there is another side to the problem: detailing the specific qualitative characteristics of discipline mastery often involves parameters that are difficult to define and operationalise, such as "dancing in an organic, highly musical, convincing, confident, and emotionally contagious way" [Federal'nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel'nyi].

Finally, we must mention a number of professional competencies that were present in the previous FSES (2010 and 2017), but not in theatre school curricula for 2021. These include:

- "willingness to show creative initiative while preparing for a drama, film, television film, circus or variety performance";

- "the ability to work with art history research, analyse works of literature and art, and use professional concepts and terminology";

- "mastery of acting analysis, both in theory and in practice, and the ability to embody works of fiction, including drama, prose and poetry, on stage";

- "the ability to navigate easily through the creative heritage of outstanding masters of domestic and foreign drama theatre".

It should be added that the competence described as "the ability to work with art history research" can, in a sense, be correlated with the general professional competence from the 2021 standard: "the ability to apply theoretical and historical knowledge in their work; aptitude for comprehending a work of art in a broad cultural and historical context in connection with aesthetic ideas of a particular historical period". However, the other competencies listed above are not reflected in the FSES or in the curricula for 2021. It should be noted that, given that the FSES and the curricula developed on its basis do not mention how the actor should "embody works of fiction, including drama, prose and poetry, on stage", be willing "to show creative initiative" while preparing for their performance, or "navigate easily through the creative heritage of outstanding masters of domestic and foreign drama theatre", this begs the question: is this kind of training truly meant to educate actors as professionals that rely on the global experience in dramatic art? We find this quite dubious.

On aptitude for acting

We should pay special attention to the terms used in formulating the competencies. The word "aptitude" makes recurring appearances. For example, in FSES 2021, all 10 universal competencies as well as 5 general professional competencies, are formulated using this term. This prompts the conclusion that educational standards often use the concepts of competence and aptitude interchangeably. Moreover, the term "aptitude" in this context lacks scientific psychological content. It is therefore important to look at the understanding of aptitude in Russian psychology.

For instance, one of the definitions of aptitude provided in the Complete Dictionary of Psychology matches the concept introduced by B. M. Teplov: "Aptitude comprises individual and psychological features that distinguish one person from another and determine how well a person can perform an activity or series of activities. These features cannot be equated to knowledge, skills, or abilities, but they do determine the ease and speed of learning new types and means of activity" [Avdeeva, 2007; Teplov, 1985, p. 16]. At the same time, Teplov noted that temperament or character traits (Teplov's examples include hot temper, lethargy, and sluggishness) do not constitute aptitude, because successfully performing an activity is not conditional upon them. However, it is worth noting here that the characteristics listed above can be categorised as professional qualities or components of professional performance: a person's individual features that are necessary for them to succeed at their activity (1; 10). Moreover, for a number of professions, particularly creative professions, such aspects of temperament and personality can be very important, and acting is no exception.

For example, contemporary researchers of actor psychology point to a number of characteristics that are important for professional acting: flexibility and stamina while working and communicating with people, ability to predict the consequences of one's behaviour, sensitivity to non-verbal and verbal expression [Makeeva, 2019]. Comparative test studies based on a variety of samples have highlighted the specific psychological characteristics indicative of an individual's predisposition to acting: sociability, courage, willingness to take risks, emotional sensitivity, inclination towards the artistic perception of the world [Groisman, 2003; Rozhdestvenskaya, 2005; Sobkin, 1984; Sobkin; Sobkin, a; Sobkin, 2018; Nettle, 2006], demonstrativeness, rich imagination, femininity, intellectual flexibility [Karpova; Nefedova, 2021].

Similar trends have been noted in foreign works. For example, comparative personality studies among actors and non-actors, using variations of the "Big Five" personality traits and other techniques, point to the qualities typical of actors: openness, extraversion, neuroticism, and higher scores for social intelligence and tolerance for uncertainty [Dumas, 2020; Nettle, 2006]. Empathy and awareness of other people's mental state can also be added to this list [Goldstein, 2012]. In addition, several studies have shown that there is a complex of specific personality traits that can be seen as a type of aptitude that ensures the actor's success when influencing the audience. Notably, the presence of these traits cannot be attributed solely to education [van Haeften-van Dijk, 2012].

It is therefore important to revisit and expand on the stance taken by Teplov, whose studies on the nature of aptitude specifically emphasised the role of the individual's inborn characteristics, as they are what, in a large number of cases, lies at the foundation of aptitude. At the same time, aptitude itself emerges and develops throughout human life, in the process of activity, represented in comprehensive cultural form. In this case, according to Teplov's ideas, the notion of aptitude should be explored specifically from the standpoint of individual differences: "no one would speak of aptitude when dealing with qualities that are equal in all people" [Teplov, 1985, p. 30].

It should be emphasised that B. M. Teplov reviews his concept of aptitude is in the context of giftedness, which in turn is crucial in analysing acting aptitude. For example, he points out that different aptitudes not only change and improve throughout their development process, but also influence one another. The resulting unique combinations of aptitudes, which determine greater or lesser success in a given activity, are what Teplov calls giftedness.

In this regard, we should note that, when referring to the actual practical side of aptitude development, Teplov highlighted a crucial point that has to do with the compensatory mechanisms of activity. In other words, an individual's lack of aptitude for a specific activity can be compensated for by a combination of aptitudes for other activities. In essence, it means that the aptitude for carrying out a given activity in its culturally developed form cannot be reduced to a single universal aptitude: "It is precisely because of the vast range of compensation capabilities, any and all attempts to reduce, for example, musical talent, gift for music, musicality and the like to a single aptitude are doomed to failure" [Teplov, 1961, p. 220]. This is true of any creative activity, including acting. We shall therefore conclude that the logic of improving the competence-based approach, as shown above, is based attempts to identify the most generalised competences, while neglecting the idea of triggering compensatory mechanisms during creative activity.

The topic of aptitude took is particularly expanded upon in the academic discussion between A. N. Leontiev and S. L. Rubinstein. Both authors agree on two main points: 1) aptitude is based on naturally inborn qualifies; 2) aptitude is expressed and shared through human activity, which in turn is expressed through the products of material and spiritual culture.

What they do disagree upon comes down to what determines aptitude. From Leontiev's point of view, aptitude, like all other human mental functions, is entirely determined by the objects and circumstances surrounding an individual's development. In other words, the specific aptitudes that will be nurtured within the individual depend on the environment where they develop, the objects around them, and the courses of action that are offered to the individual by the surrounding physical and cultural environment [Leont'ev, 1960].

Rubinstein, on the other hand, notes that Leontief pays too much attention to external causes and conditions of mental development, while barely considering internal determinants. This emphasis on external factors in aptitude development essentially reduces aptitude to "absorbing a set of historically developed operations" [Rubinshtein, 1960, p. 13]. On the one hand, this approach to aptitude makes it accessible for almost any individual to gain, while on the other hand, it erases manifestations of individuality, and therefore the potential for nurturing giftedness. The individuality that Rubinstein writes about is, in this case, determined by the subject's activity during the formation and development of their aptitude. For instance, using mental aptitude as an example, Rubinstein notes that it is not enough to merely master ready-made action patterns. Creating "internal conditions for their productive use" is also essential [Rubinshtein, 1960, p. 15]. The successful development of mental aptitude requires considering the relationship between the internal and external conditions that determine them. Here, we must mention what is perhaps the key criterion: "Nothing is such an obvious indicator of mental giftedness as the constant emergence of new thoughts in the individual's mind" [Rubinshtein, 1960, p. 20]

In analysing this discussion, E.V. Ilyenkov additionally defines one of the most important components of aptitude: "the ability to take action where there is no predetermined way of acting, or no indication as to which specific pre-set operation should be chosen. After all, the ability to act in a situation of this kind is precisely what distinguishes someone with aptitude from someone 'inept', a more capable person from a less capable one..." [Il'enkov, 2002, p. 69].

Note that the central point of the polemics between Leontiev and Rubinstein is the subject that is performing actions, and this subject's abilities. This discussion was productively continued by D. B. Elkonin and V. V. Davydov in their theory and practice of developmental learning [Davydov, 1996]. And perhaps it is here, in the context of aptitude, that such basic aspects of subjectivity as initiative, autonomy and responsibility gain fundamental importance [Sobkin, 2006]. Characteristically, the very idea of the subject's formation follows the logic of L. S. Vygotsky's concept of proximal development zone: more broadly, the relationship between the child and the adult as a cultural mediator. We believe that these two particular points are fundamental in addressing the development of creativity.

Returning to the competence approach in relation to the Leontiev-Rubinstein discussion, we note that in, the FSES the term "aptitude" is used for describing the students' shared outcomes of completing an educational programme. In this respect, this use of the term is close to A. N. Leontiev's interpretation of aptitude as a set of operations, which, as we noted, S. L. Rubinstein was justifiably critical of. In addition to this, there is another side to the issue: mastering competencies usually implies undergoing the assessment of one's knowledge, skills and abilities, which, as we have tried to show, creative aptitude (in our case, acting) cannot be reduced to in a psychological sense.

Conclusions

- The competence-based approach that underpins the modern FSES aims to ensure the uniform and universal nature of the academic environment, provide all students with equal opportunities, and make high-quality education more accessible. However, the creative nature of the acting profession and the peculiarities of mastering it call for identifying and developing a very unique set of aptitudes, which B. M. Teplov calls giftedness. The analysis in the article shows that the task of identifying the student's aptitude for acting is addressed at the university application stage. The educational process itself focuses on the individual approach and the further development of the student's set of aptitudes that make them a gifted actor. Thus, the notion of aptitude, rather than competence, is central to the development of psychological criteria for successful training in the acting profession.

- The analysis of approaches to the concept of aptitude in Russian psychology (B.M.Teplov, A. N. Leontiev, S. L. Rubinstein) and developmental learning theory (D. B. Elkonin, V. V. Davydov) allowed us to conclude that aptitude is an important characteristic of an individual's subjectivity (motivation, goal-setting, etc.). At the same time, subjective characteristics not usually captured by the term "competence", the essence of which is limited to the acquisition of knowledge, skills and abilities. Thus, during training for creative professions, the development of aptitudes, as explored by the activity theory, is what can lay the psychological foundation for organising the educational process.

- Establishing a psycho-pedagogical service in higher education is, we believe, highly relevant to training students in creative professions. This service should provide, on the one hand, psychological and pedagogical support for the educational process and, on the other hand, psychological support for students. In both cases, it is the term "aptitude" rather than "competence" that can serve as a key concept when addressing the students' personal problems in the context of their professional work. The work of such a psychological service will not only contribute to the harmonious development of the students' personalities, but will also improve the academic value of the training process.