Introduction

It is no secret that one of the most dire consequences of the “EGE-ization” of education has been the loss of motivation among school students. Restoring this motivation is a significant challenge at present. Maintaining an ininterest in knowledge and cultivating curiosity during the learning process is a crucial aspect of pedagogy. It is essential for curiosity and interest to accompany students’ academic activities, whether in traditional subjects or in project-based learning. The erosion of interest and curiosity has also been exacerbated by thecreation of specialized educational tracks in the general secondary education system (A.A. Pinsky and other members of the educational team at the Higher School of Economics). A student placed in a specific track often assumes that knowledge, concepts, and facts from disciplines outside their track are irrelevant and unworthy of attention. Drawing on Isaiah Berlin’s well-known distinction between “foxes” and “hedgehogs” (Berlin, 1957), this approach produces narrowly specialized “hedgehogs” who bury themselves in details and lack the ability to see the broader context, while preventing the development of “foxes” who explore vast fields of knowledge. However, project development requires “foxes” whose cognitive and learning strategies are rooted in curiosity (Berlyne, 1954; Kahan et al., 2017; Motta et al., 2019).

Today, gamification methods are increasingly being used as a means to address the decline in motivation. These methods are gaining widespread adoption and, consequently, are becoming the subject of various psychological studies.

Here are some key thematic areas that currently attract significant interest among educational psychologists:

- The impact of games on the development of competencies and abilities of students (Rubtsova, Salomatova, 2022a; Rubtsova, Salomatova, 2022b; Rubtsova, Ulanova, 2014; Obukhova, Tkachenko, 2008).

- The influence of games on students’ educational motivation (Borzenko, 2016; Zakharova, 2024; Burakova, 2023; Lipatova, Khokholeva, 2020).

- The need for changes in pedagogical professionalism amid increasing gamification (Duong, Vo, 2024; Bogdanova, 2022).

- Analysis of international and domestic practices of educational gamification (Annetta, 2008; Ermakov, 2020).

- Analysis of well-known games, such as Minecraft, used in education (Driantsev, 2018; Tablatin, Casano, Rodrigo, 2023).

Despite the broad range of research on the effects of gamification in educational practice, one specific aspect remains underexplored: the integration of project-based activities into gameplay. Researchers focus on how games can be used for “peaceful purposes” to develop or maintain perceptual and cognitive processes. However, games were originally created by the entertainment industry for entirely different goals—such as capturing attention through repetitive computer keystrokes. Integrating project-based activities into gameplay implies that either the game format and rules must become the subject of transformation by students and educators, or students must tackle complex scientific or practical problems within the game. By engaging with unsolvable problems, students explore the complexity of the issues without claiming socially significant or publicly recognized results. Yet, this exploration should not lead to arbitrary simplifications or the rejection of specialized scientific knowledge or to fictions about the social context. This type of a practical problem formulation and of self-determination of adolescents in relation to this problem requires the development of a special game form. Existing board games and video games do not have this game form.

Using pre-existing, unmodified video or board games risks regressing students from higher-level cognitive activities to more primitive forms of preschool play with arbitrary rules, even if the outcomes are taken seriously. While games that challenge players to overcome limitations can yield meaningful educational results, this requires specially designed game formats that demand thoughtful and significant effort from participants.

Meanwhile, project-based activities are the leading developmental activity for older adolescents (Gromyko Yu.V., 1997; Gromyko N.V., 2023), despite modern schools’ focus on standardized exams and Olympiads, which often neglects teaching these skills. Project-based learning, as a distinct type of activity — not to be confused with so-called “individual projects” that may include anything from essays writing and advanced school subjects learning to robotics design — is crucial. We argue that the key issue in adolescent development theory is the cultivation of project-based consciousness as a modern sociocultural form of practical consciousness (V.V. Davydov). Practical consciousness, linked to career choices, adult life, and the desire to assess social situations maturely, has always been relevant for older adolescents and young adults.

V.V. Davydov rightly noted that older adolescents and young adults begin to grapple with practical questions: How to act ethically? Should ethics be followed if many adults disregard them? How are power and wealth inherited despite proclaimed social “elevators”? To what extent do declared principles align with actions? How does the world change? How to earn a living in today’s society? These unresolved societal contradictions can only be resolved from the point of view of thinking through the structure of our entire society. Such work requires self-determination and collective problem-solving, which can only be addressed through project-based consciousness — a forward-looking sociocultural mindset. Thus, adolescents must learn to analyze social situations, set problems, and develop project-based solutions while considering diverse perspectives. Integrating such project-based activities into specially designed games is essential. Without this, we risk infantilizing older students, preventing them from engaging meaningfully with societal challenges.

The increasing gamification of education for older adolescents, while ignoring that their leading activity is no longer play or study but project-based work, may further isolate them from society and delay personal maturation. Temporary motivation sparked by games, without understanding how knowledge applies professionally in modern society, quickly fades.

Unfortunately, many games offered by the entertainment industry exacerbate this issue, reinforcing infantilization rather than fostering project-based skills. For games to be truly developmental for adolescents, they must incorporate project-based elements, requiring transformative changes to game formats and environments.

Even the most in-depth psychological studies on gamification’s impact on learning (Margolis et al., 2021; Margolis et al., 2022; Rubtsova et al., 2023; Rubtsova, Panfilova, Artemenko, 2018) focus on adapting existing games on the base of diagnostic research so that they facilitate educational process in any way rather than transforming them to foster project-based thinking.

Below, we describe our method for transforming a board game into a project-based game.

Method of converting the educational game focused on memorizing subject information into the project-based learning game

For the material for transforming one of these board games into a project-oriented game, we selected a game by V.O. Poluga, head of the i-Cube Centre for Educational Consulting, which specializes in, among other things, developing and commercially producing board games. V.O. Poluga is a graduate of the first cohort of our Master’s program opened in 2019 at the Federal State Budgetary Institution of Higher Education “Moscow State Psychological-Pedagogical University,” specializing in “Pedagogy and Psychology of Project Activity in Education.”

For our adaptation and transformation into a project-oriented game, we chose just one of his games—”Cito-logic.” This game is centered on cellular structure knowledge.

The basis of the game is a chart that students must know from their eighth-grade biology course (Cell Structure ..., 2021). It lists organelles, their structure, and functions. In V.O. Poluga’s game, students draw separate cards featuring organelles and their functions, then properly match them together, eventually memorizing the material required for passing the Basic General Education Exam (OGE) and Unified State Exam (USE).

Unlike V.O. Poluga’s games, the specificity of our educational-technology-based approach to running project-educational games lies in its focus on helping students acquire theoretical concepts, universal thinking principles, and metasubject methods of work. Our approach targets the development of project thinking and introduces students to the basics of design activity. Crucially, unlike the educational-gaming approach employed by V.O. Poluga and his team, our technology uses games to guide students from a foundation of thoroughly processed basic school-level knowledge to the forefront of scientific discovery and engineering innovation. We engage students in searching for answers to real scientific problems. Meanwhile, V.O. Poluga’s games are purely mnemonic in character, treating knowledge simply as informational labels that must be arranged correctly on the table and remembered.

Next, we’ll discuss the technique we’ve developed for the project-game module “Life on the Moon,” geared toward teaching design within an educational-playground context. Unlike a full-scale project activity cycle lasting at least one academic year, this module lasts for three days. It can be used either as a primer for project activity or as an intensive workshop for practicing isolated segments of the project cycle (formulating project ideas, reanalyzing situations, translating project ideas into task frameworks).

First and foremost, it should be emphasized that for cell biology concepts to acquire genuine motivational value for students, they must be connected to open-ended, problematic questions from the perspective of contemporary knowledge. This approach immediately shifts students from the familiar schoolchild position where “the teacher knows everything but asks anyway” to the realization that there is no definitive answer to the problematic question. In the “Life on the Moon” game, these problematic questions are: “What is life?” and “How to explain the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes?” There is no single correct answer to these questions. Engaging students in designing methods to address these unresolved, open-ended questions serves as a powerful motivational tool, encouraging them not only to play but also to pursue knowledge beyond the game.

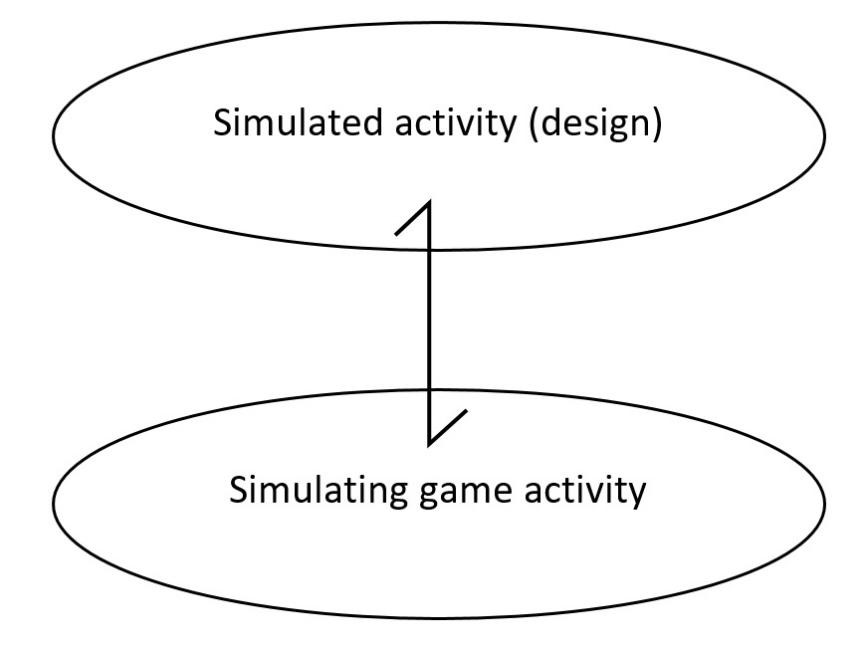

For the game to effectively develop project-based thinking, it must simulate project-based activities where such thinking naturally occurs. In other words, when designing such a game, it is crucial to maintain the relationship between: 1) the activity that gives rise to project-based thinking, 2) project-based activity itself, and 3) the game-based activity being designed (Elkonin, 1999; Gromyko Yu.V., 1992; Skobelev, Gromyko Yu.V., 2022; Gromyko Yu.V., 2023) (Fig. 1).

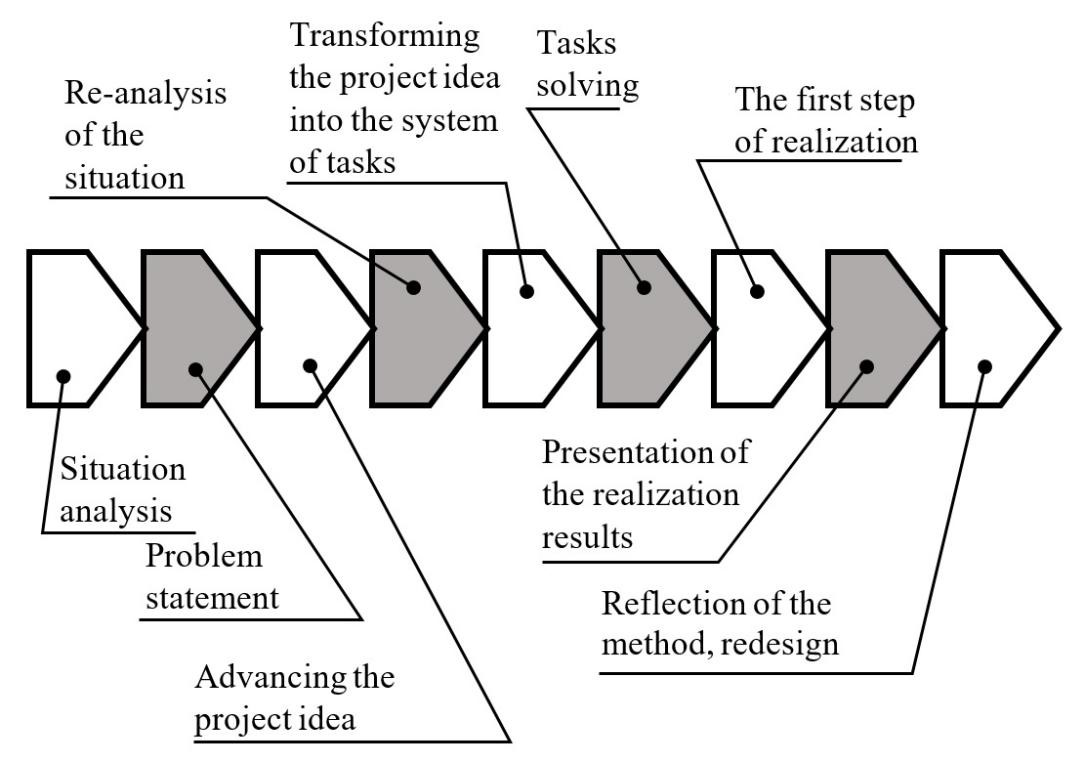

Project-based activity is a sequence of stages illustrated in Fig. 2 (N.V. Gromyko, 2020). Implementing each of these stages requires specific cognitive abilities such as reasoning, comprehension, imagination, and reflection; these abilities facilitate the emergence of project-based thinking. Because it is anticipated that these abilities will be partially activated and partially formed during the game, the game requires:

a) group communication, through which these abilities will manifest; hence, the game should involve groups rather than individuals;

b) support from game-designer educators who will organize group communication and detect, encourage, and strengthen the manifestation of these project-based thinking abilities;

c) reflexive format, which makes project-based thinking objective for its participants.

The entire scope of project-based activity cannot be transformed into a game because framing a problem or conceiving a project idea as a pretense would instantly be perceived by students as artificial and insincere, thereby demotivating them. If, however, the problem and project idea are framed sincerely, the playful element vanishes, and the game turns into genuine project work. A way out of this predicament, as noted earlier, is to introduce students to an already existing problem. It is essential to demonstrate that the problem they are being introduced to actually exists: in science, there are two approaches to what constitutes the fundamental property of living systems. One predominant approach, reflected in school and university textbooks, holds that this property is the ability to replicate and reproduce similar systems. Another approach, rooted in Ervin Bauer’s work “Theoretical Biology” (Bauer, 2002), states that the most important property of a living system is its operation against equilibrium, leading to an increase in the system’s free energy.

Additionally, students need to realize that this problematic question is not merely an amusement for scientists accustomed to “satisfying their own curiosity at the state’s expense” (Academician L.A. Artsimovitch). The question of the essence of life and its fundamental distinction from non-living matter is one of the key questions in the scientific research agenda initiated by our fellow countryman Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky, aiming at comprehensive investigation of life as a planetary and, more broadly, cosmic phenomenon. Knowledge of the fundamental principles of life, in particular, could help increase human lifespan — especially active life — by at least twofold.

Knowledge of the fundamental property of living systems is also important for socio-economic systems. Social-engineering achievements in constructing societies and identities ad hoc raise questions about whether such constructs are viable systems or rapidly disintegrating simulacra, and how they interact with “alive” socio-economic systems. Answering this question requires the ability to differentiate between living and non-living entities by studying both biological and socio-economic systems.

All subsequent game-competitions unfold around the question: how to determine which of the two mentioned approaches is valid? How can we establish what underlies life: replication or accumulation of free energy? The cultural tool for answering such questions, as well as winning our game-competition, is an experiment (or, more accurately, a critical experiment). Its essence lies in the following: it is necessary to envision a process whose theoretical modeling, within each of the alternative approaches, yields different results. Subsequently, the practical realization of this process should be executed, observing which of the theoretically predicted outcomes materialized. Precisely in this manner, Foucault demonstrated Earth’s rotation using a pendulum, and similarly, Arago confirmed the wave nature of light by displaying Poissin’s spot.

To organize the critical experiment, a new task is proposed: analyze the process of the emergence of eukaryotes (nucleus-containing cells with mitochondria) from a collection of prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) mutually beneficial to each other through syntrophy (Non-Simple Evolutionary Routes …, 2019). The theoretical modeling of this process, which occurred on Earth roughly 2 billion years ago, shows a difference in the rate of this process from the perspective of the alternative approaches: the replication-based approach assumes that the formation of eukaryotes was a pure chance event caused by mutation; meanwhile, the energy-based approach maintains that this event involved considerable regularity, driven by an evolutionary trend favoring the formation of eukaryotes, as they possess much greater amounts of free energy compared to the prokaryotes from which they originated.

However, on Earth, the formation of eukaryotes has already happened, dramatically altering the conditions on our planet by giving rise to the biosphere. Therefore, reproducing this transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes on Earth, saturated and modified by life, is nearly impossible. Such an experiment would last not just decades but perhaps even centuries, with terrestrial life inevitably interfering with laboratory conditions. Thus, it is proposed to conduct this experiment intellectually-theoretically on the closest celestial body devoid of life (abiotic) — the Moon.

How can this be achieved? This question is what the student project teams must answer. Whichever team accomplishes this faster and more efficiently — wins.

Description of the educational gaming module “Life on the Moon” targeted at project-based learning

The educational gaming module “Life on the Moon,” outlined below, has been tested at the L.S. Vygotsky Memorial TechnoPark “Kvantorium” of Moscow State Psychological-Pedagogical University (MSPPU) and at the School No. 597 “New Generation” in Moscow.

The module is divided into two parts: a preliminary phase and the actual game. The preliminary phase encompasses introductions to the problem of living matter, the conception of the experiment, and its theoretical modeling. During the game phase, students tackle the practical implementation of the experimental procedure by competing to design an experimental device suitable for functioning under severe lunar conditions. On the diagram illustrating project-based activity (Figure 2), this corresponds to stages of repeated situation analysis and task setting.

During the preliminary phase, students work with texts presenting the content of each of the alternative approaches to defining what constitutes living matter, alongside a description of the hypothesis of eukaryote origins from prokaryotes. Their task is to comprehend the essence of each approach, highlight their distinctions, and execute theoretical modeling of the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, grounded in the assumptions of each respective approach.

In other words, students are required to complete the following tasks:

a) Understand what the texts say about different approaches to defining living matter and formulate this understanding as a thesis statement articulating what living means according to the presented approach.

b) Express this understanding not only verbally but also visually through diagrams.

c) Recognize that theses and diagrams about what constitutes living are fundamentally different and irreconcilable.

d) Use the gained understanding derived from each text to respond to the question of how the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes took place.

e) Based on:

- understanding,

- schematization,

- working with disciplinary concepts,

- modeling (building models using disciplinary terms),

- simulation (using models to describe real processes),

- recognize that, depending on the differing approaches, the transition is described in different ways. This divergence in theoretical modeling results can be used to design a critical experiment.

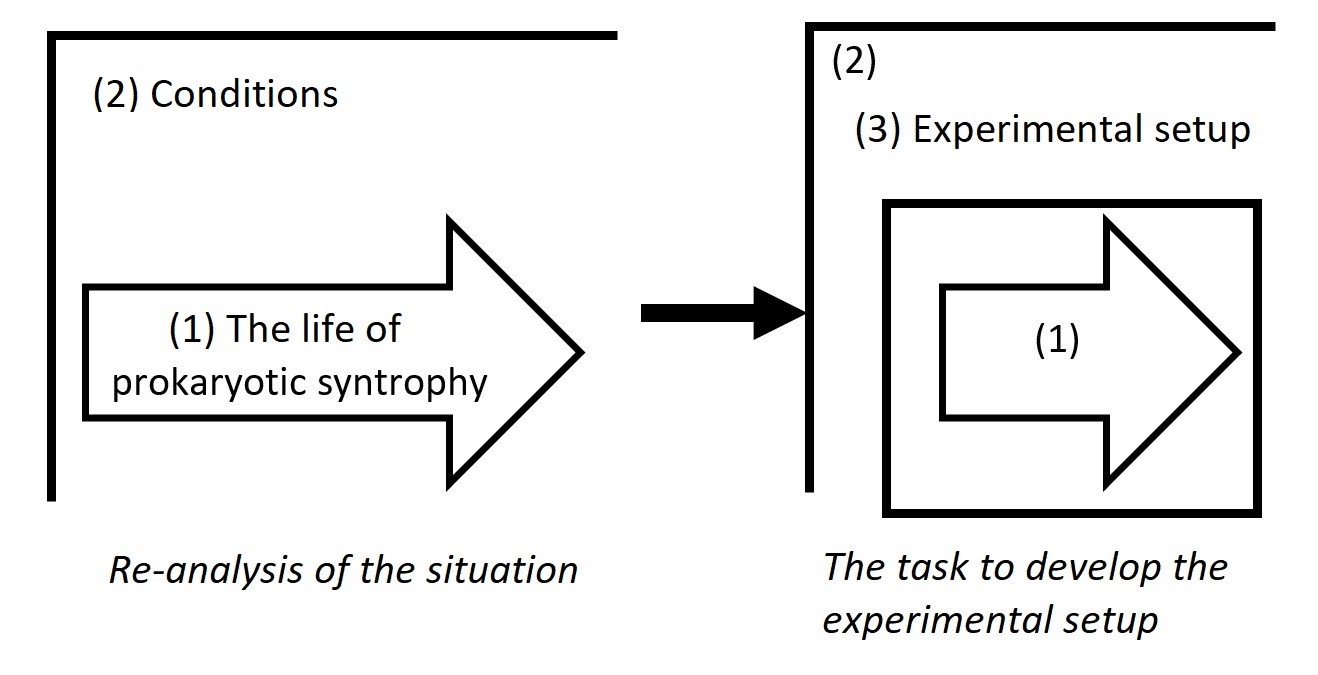

The progression of project groups during the game phase “Launch Life on the Moon” follows this framing project task: “Design a device enabling the survival of a colony of prokaryotes engaged in syntrophic relationships under unlimited time in lunar conditions.” Throughout the game, this project task transforms into multiple subtasks, which project groups must accomplish:

- Specify the project concept: transform the abstract notion of “syntrophy” into a descriptive instrument detailing the process to be implemented during the experiment.

- Reanalyze the situation taking into account the conditions for implementing the experiment (the conditions on the Moon).

- Propose a constructive solution allowing the execution of the experiment under specified conditions (see Fig. 3).

At this point, it is worth recalling that psychology still lacks consensus on what drives the generation of project concepts: is it imaginative capacity (N.N. Nechaev) or theoretical thinking (Yuri V. Gromyko)? Our work with students within this constructed gaming module supports our hypothesis that it is indeed theoretical thinking, as it proves impossible to generate a project concept without reliance on the previously discussed theoretical constructs.

The player’s movement is facilitated by the following game tasks.

Task #1 within the game.

- Using the text “Complex Pathways of Evolution: Where Did Eukaryotes Come From?” compile a set of prokaryotes that, interacting with each other, can exchange substances (engage in syntrophy) relatively independently of their external environment.

- Draw a scheme showing the substance-exchange process within your selected group of prokaryotes, as well as between the group and the external environment. Illustrate exchanges involving six key chemical elements both inside the prokaryote group and between the prokaryotes and the environment.

Task #2 within the game.

- Your compiled group of prokaryotes is now relocated to the Moon. List the most important characteristics of the Moon that must be considered for the process of syntrophy to occur between the prokaryotes.

- Explain why you believe these listed characteristics are significant for your group of prokaryotes.

- Determine additional information about the Moon that is needed to make the experiment as successful as possible.

- Present your team’s conclusions in the form of statements and a table.

Task #3 within the game.

- Propose a design for an experimental installation in a lunar laboratory capable of supporting the life of your group of prokaryotes.

- Sketch the installation.

While completing the tasks, students collaborate with teachers, who act as game characters: the critic named Moon, consultants Program Vernadsky and Herald of Academy of Sciences. Consultants do not complete tasks for students but provide necessary domain-specific knowledge (biological and astrophysical respectively). Teachers, serving as game characters, assume roles on one side, while simultaneously facilitating the educational process — including mastery of theoretical concepts, metasubjective technologies, and foundations of design activity.

When designing the experimental facility, students combine three types of knowledge: biological (including biochemistry), captured in the scheme of syntrophic interaction; astrophysical (specifically selenological), recorded in the table of significant lunar conditions; andengineering, embodied in the construction of the experimental setup. Consequently, evaluations of their work proceed from three positions: biologist, astrophysicist, and engineer. Communication between players designing the experimental setup and representatives of these three fields helps students grasp the essence of each position, thereby stimulating project-based thinking.

Thus, distributed collaborative form of activity is represented not only in interactions among students within their groups and discussions of others’ results at general meetings, but also in interactions between student-gamers and teachers/game characters, as well as with experts, each contributing from their specific disciplinary-practical standpoint.

To conclude, this educational game module seeks to introduce students, starting right from school benches, into pioneering scientific practices carried out by institutions such as American NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), Chinese Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (SASC), and Roscosmos, tackling the question of how to recreate life in the conditions of another planet. Playing to find answers to this question, supported by solid theoretical concepts, exposes students to a world beyond pseudo-scientific fantasy — revealing to them the real Future.