Introduction

Among the modern requirements for primary education outcomes, so-called metadisciplinary educational results play a significant role. These include the ability to experiment, establish cause-and-effect relationships, draw conclusions, and justify them based on experimental results and measurements. Similar requirements are also recorded in the subject-specific outcomes of the "The World Around Us" course (Order of the Ministry of Education of Russia, 2021). The achievement of these results is assessed, for example, in one of the tasks of the All-Russian Verification Work (VPR) in the 4th-grade "The World Around Us" test (VPR, 2023). This task assumes that a primary school graduate is not only capable of reading and understanding informational texts but also of planning an experiment to test a hypothesis, recognizing the differences between an experiment and a control test, and identifying the necessity for appropriate measurements.

However, methodological literature lacks justification for the necessity of introducing experimentation in primary school, an understanding of the extent to which these skills should be mastered, and an analysis of approaches teachers use to implement this task. This gap is partly due to the insufficient psychological research on the issue. Most psychological and pedagogical studies show the positive impact of early training in scientific methods on students' cognitive development, abilities, knowledge, and personal qualities (Abualrob, 2019; Levy & Mensah, 2021; Oktaviani et al., 2023; Siti et al., 2023; Twizeyimana et al., 2024; Zainil et al., 2023). These studies emphasize students' growing interest in studying the world around them when learning is based on real experimentation (Trofimova, 2024; Lewis, 2019) and highlight the teacher's role in setting tasks and the need for changes in teacher training (Sanina, 2023; Estapa & Tank, 2017; Stari et al., 2020). Only a small portion of the research focuses on analyzing the actual process of experimentation and studying difficulties in mastering it (Osterhaus et al., 2016; Valanides et al., 2014). Some researchers (Osterhaus et al., 2016) note that children struggle to learn how to control experimental conditions and conclude that this skill can only be fully developed between the 4th and 6th years of schooling.

To develop or evaluate methodological approaches to teaching, it is first necessary to provide a psychological characterization of experimentation as an activity to be mastered in primary school. This involves conducting a logical-subject matter and logical-psychological analysis of educational content. V. V. Rubtsov states: "According to V. V. Davydov, psychological and pedagogical research must integrate logical-subject matter and logical-psychological analyses of educational content and teaching methods. The approach to children's developmental potential should be seen not as something predetermined but as something that unfolds and takes shape during formative experimentation" (Rubtsov, 2005, p. 17). The results of these analyses serve as the foundation for designing formative experiments that allow researchers to identify and describe the process and outcomes of mastering this content, as well as to determine students’ developmental potential and possible difficulties. This, in turn, helps develop both methodological approaches to teaching and strategies for training teachers to achieve the Federal State Educational Standards (FSES) results.

Experimentation, as a method of obtaining answers to questions posed to nature, has been known since antiquity. Over centuries, it has evolved and improved, becoming the foundation of modern science (Akhutin, 1976; Stepin, 2000; Suvorov, 1972). Unlike targeted observation or practical trials, experimentation involves comparing two identical objects (or one object at different points in time) under different conditions. In modern scientific experiments, issues of reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility are crucial (see Stepin, 2000). However, these issues are not relevant to teaching young students. Thus, we focus on basic experimentation, emphasizing only its fundamental aspects. Basic experimentation involves comparing two objects rather than two large (statistically meaningful) groups of objects. Another key characteristic of basic experiments is their single-variable nature — only one factor is manipulated at a time.

Experimentation is a conscious and planned activity primarily defined by a hypothesis, a proposed explanation of a process. In science, hypotheses are often derived "from theory" through deduction, meaning they are logical conclusions. However, in basic experimentation, hypotheses are usually formulated through intuitive insights about potential relationships between objects or processes — similar to how new theories are created (see Suvorov, 1972). This has implications for teaching: students cannot be directly taught how to formulate hypotheses. Instead, learning environments should provoke students into making hypotheses, thereby stimulating the development of this ability.

Some hypotheses may be unverifiable due to a lack of necessary tools, while others are fundamentally unverifiable. In basic experimentation, students often propose hypotheses with vague formulations that cannot be operationalized, such as "Dandelions close because of the weather."1

As a result of mastering basic experimentation, students should be able to plan an experiment according to a given hypothesis. The key components of such a plan include:

- Two comparable objects (experimental and control).

- Identification of different conditions for experimental and control objects, based on the hypothesis.

- Equalizing other conditions for the experimental and control objects.

- Formulating predictions about the expected outcomes for both scenarios (if the hypothesis is correct or incorrect).

An important aspect of experimentation, even in its simplest forms, is the recording and description of results as well as the derivation of conclusions (for more details, see Chudinova & Shishkina, 2024). These aspects have also been highlighted in studies on young children's understanding of experimental design. However, such studies primarily focus not on how these skills can be developed, but rather on measuring children's achievements (Osterhaus et al., 2016). The questions of distinguishing what is observed from what is inferred, as well as differentiating between results and conclusions, are highly interesting. However, they require a separate study and will not be addressed in this paper.

A logical-subject matter and logical-psychological analysis of experimentation allows us to understand its significance for the development of thinking and consciousness. Mastering basic experimentation lays the foundation for understanding causality and enables a clear distinction between temporal and cause-and-effect sequences of events. Erroneous conclusions such as "My wife got sick after vaccination, therefore the vaccine caused the illness" are common not only among children but also among many adults.

Causal reasoning is fundamental to scientific knowledge and school subjects built upon it. A. V. Akhutin, describing Galileo’s experiments, notes: "These countless experiments possess the ability to prove even before they are actually conducted… Galileo thinks experimentally, within experiments, through experiments, yet he is always already convinced of the truth of the result before conducting the experiment" (Akhutin, 1976, p. 3). Essentially, Galileo demonstrates the explicit verbalization of scientific reasoning, a process that in modern scientific articles is often implicit.

The above means that textbooks on physics, chemistry, biology, and astronomy cannot be fully understood by students without mastering this fundamental way of thinking and acting. Therefore, introducing basic experimentation in primary school is essential.

Unlike other primary natural science courses (grades 1–4), in the Elkonin-Davydov educational system, the method of basic experimentation is discovered by children through collaborative and distributed learning activity, using the example of pinecones closing in humid weather. The learning task of finding a method of action arises when trying to explain what happened to the pinecones that were lying open on the path yesterday with spread-out scales and are now closed. A concrete-practical version of the task is formulated as "make the open pinecones close." The versions proposed by the students ("because of the cold," "because of the darkness," "because of the humidity," etc.) are initially not hypotheses; they become hypotheses in the process of encountering different possible answers and realizing that it is unknown which one is correct. The familiar method of observation, which the students attempt to use to confirm one of the versions, does not work because the teacher creates a situation where all the mentioned conditions change simultaneously.

The students search for a new method, coming up with a way to ensure that only one condition changes (has an effect), for example, cold. The idea of placing a pinecone in the refrigerator turns out to be insufficient because "what if it would close even without the refrigerator?" This reveals the necessity of a control object (another pinecone), which needs to be placed in a warm environment. Another mental step involves the idea of equalizing all other conditions: "if it is dark in the refrigerator, then the pinecone placed in warmth must also be in darkness; otherwise, it will be unclear whether it closes due to cold or darkness."

The newly discovered method of answering questions is compared to previously known observation techniques, and the necessary actions are recorded in a symbolic-representational scheme. The method is then practiced through experimentation with other natural objects (see Chudinova & Shishkina, 2024). The duration of this stage of learning is approximately eight lessons.

Materials and Methods

The research hypothesis stated that full mastery of experimentation, even in its simplest form, requires students to independently discover this method of action and understand it within the framework of structured learning activities. A simple explanation and demonstration of experiments, as well as the independent execution of simple experiments according to ready-made instructions (the traditional teaching approach in the World Around Us course within the School of Russia system, which is used in the majority of schools in the country), cannot ensure the development of the skills required by the Federal State Educational Standards (FSES).

Accordingly, the first objective of our study was to conduct a logical-subject matter and logical-psychological analysis of experimentation as a method of action that should be mastered by primary school students. This analysis was partially conducted earlier (Chudinova & Shishkina, 2024) and was briefly described as basic experimentation in the introduction of this study.

To assess the ability of primary school students to plan a simple experiment, understanding the differences between an experiment and a control test, a diagnostic method was developed, consisting of three tasks. All these tasks were used only for diagnostics and were not included in the teaching process. In the first task, students were required to predict the result of a given simple experiment in case the hypothesis was correct. In the second, they had to indicate the conditions necessary for control, in accordance with the hypothesis. In the third, they had to choose the appropriate conditions for conducting the experiment in accordance with its objective:

- Masha thinks that seeds need moisture to germinate. She took a saucer (A) with wet cotton and placed 5 seeds on it. Then Masha took another saucer (B) with dry cotton, placed 5 seeds on it, and put both saucers in a warm place. What will happen if Masha is right?

- Kolya hypothesized that saltwater freezes faster than tap water. He took two plastic cups. In the first cup, he poured water, added and stirred in salt, then placed the cup in the freezer. Fill in the table to indicate what should be done with the second cup to test Kolya’s hypothesis.

|

First Cup |

Second Cup |

|

100 g of water |

? |

|

One tablespoon of salt |

? |

|

Placed in the freezer |

? |

-

Different objects (cubes, spheres, eggs) were placed near seagull nests to observe how the seagulls would interact with them. Some rounded objects (spheres, eggs) were rolled into the nests by the seagulls, while objects of other shapes were ignored. This allowed scientists to conclude that seagulls recognize shapes.

What objects should be offered to seagulls to determine whether they can distinguish colors? Mark the appropriate objects with a cross (☒).

☐ small wooden red spheres

☐ small metallic shiny spheres

☐ small wooden blue eggs

☐ small wooden white spheres

☐ large wooden yellow spheres

☐ small wooden yellow spheres

This work was offered to students completing the fourth grade in a Moscow public school (25 students, including 10 girls and 15 boys) as well as to students from two second-grade classes at the end of their second year of study in the same school (50 students, including 20 girls and 30 boys). For comparison with this group and to analyze the process and difficulties involved in mastering basic experimentation, we included a second-grade class from another Moscow public school where students studied the World Around Us course within the Elkonin-Davydov system (27 students, including 14 girls and 13 boys). This comparison was preliminary; therefore, we did not account for many other factors that could influence students’ results—such as the educational level of parents or teachers’ teaching experience.

Among the research tasks, in addition to testing the hypothesis, was the analysis of children's difficulties in discovering and mastering the method to clarify the age-related capabilities of younger students. Therefore, in the school where teaching was conducted according to the Elkonin-Davydov system, participatory observation was carried out, and an analysis was made of video recordings of lessons introducing experimentation and lessons for specification (three video recordings), as well as the results of three small assessment tasks (variations of task 2 from the diagnostic work, differing in the hypotheses and materials of the described experiments).

Two similar assessment tasks were conducted one week apart, the third one a month after studying the topic, and at the end of the school year, the final diagnostic work presented above was carried out.

Results

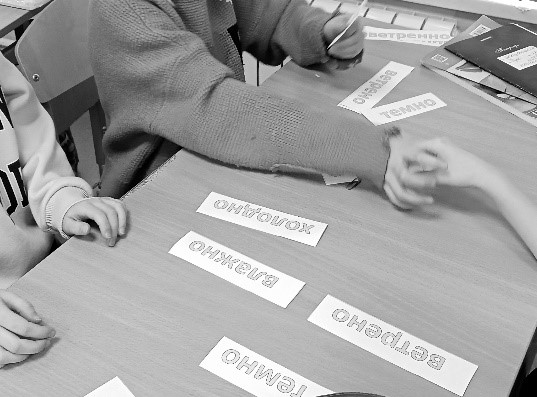

The learning task of discovering experimentation, conducted in a class taught according to the Elkonin-Davydov system, was challenging for students. In particular, the question that prompted the idea of comparing two pinecones posed significant difficulties. When this idea arose in class, the teacher proposed a straightforward approach to contrasting and equalizing conditions in planning specific experiments with the pinecones (Fig. 1).

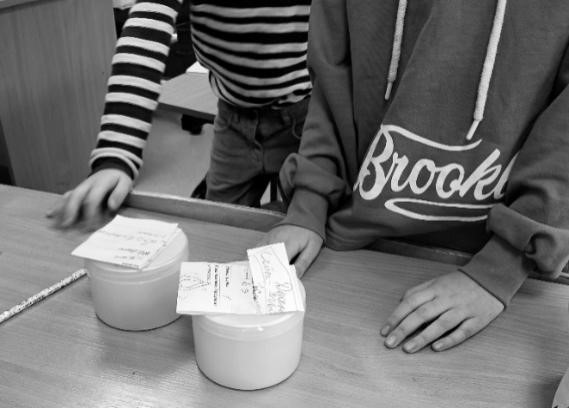

This allowed the children to work both at the board and at their desks (in groups), reasoning about the conditions of the experiment while arranging corresponding labels with written condition options in front of them. The experiment with the pinecones was conducted (Fig. 2), and its results were discussed in the next lesson.

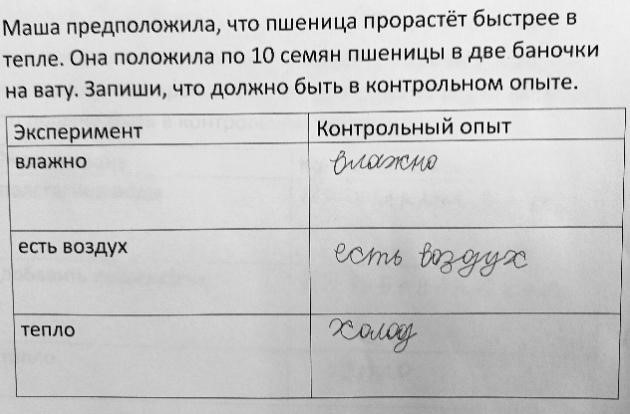

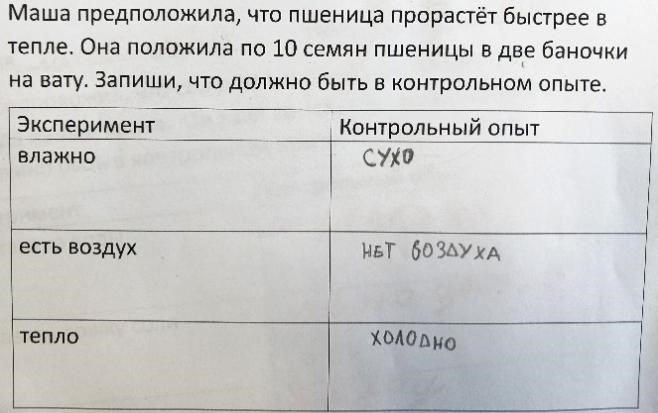

The first assessment, conducted at the beginning of the lesson following the lesson on discovering the new method of action, showed that 33% of the students clearly understood how to proceed in testing their hypothesis and were able to consciously plan the verification of another hypothesis independently (Figs. 3 and 4). This indicates that they grasped and retained the essence of the method since they had to apply it to a new, unfamiliar material.

In subsequent lessons, the learning task was extended to other similar materials (e.g., experiments with water and snow, planning experiments on seed germination). In solving each task, students had to construct logical reasoning about possible outcomes based on their hypotheses: what would happen to the experimental and control objects if the hypothesis was correct, and what if it was incorrect? If experimental conditions were not properly organized, a binary assessment of results became impossible because other factors could not be excluded. When two conditions changed simultaneously, it was unclear which change led to a particular result. Consequently, there was a need to revise the experimental plan.

Over a month (two lessons per week), students were given various tasks related to planning and conducting basic experiments. Afterward, the class moved on to studying the next topic. The comparative results of the diagnostic test conducted at year's end are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of the final diagnostic assessment (average problem-solving index [%])

|

|

Basic experimentation learning, Elkonin-Davydov system, 2nd grade classes. |

Traditional learning in the World Around Us course, 2nd grade classes. |

Traditional learning in the World Around Us course, 4th grade classes. |

|

Prediction of the result if the hypothesis is correct (0/1 points). |

502 |

22 |

44 |

|

Identification of control conditions (0/1 points). |

69 |

52 |

80 |

|

Selection of objects for the experiment (0/1/2 points). |

19 |

7 |

30 |

|

Average result for the three tasks (out of 4 points). |

39 |

22 |

46 |

Discussion of results

The table shows that fourth-grade students studying under the traditional program do not sufficiently possess the skills required by the Federal State Educational Standards (FSES), with only a 46% success rate in solving problems. Similar findings are reported by other researchers: large-scale studies indicate that fifth- and sixth-grade students correctly solve experimental tasks in about 50% of cases when provided with contextual support such as illustrations or multiple-choice answers (Osterhaus et al., 2016). Second-grade students who purposefully discovered and mastered basic experimentation performed tasks on planning experiments and predicting their results at approximately the same level as primary school graduates, and significantly outperformed second-grade students studying under the most widely used World Around Us program. To compare the success rates among children with different levels of mastery in experimentation, the Mann-Whitney U-test was employed. Statistically significant differences were found between second-grade control and second-grade experimental classes (p = 0,009), while no significant difference was observed between fourth-grade control and second-grade experimental classes (p = 0,117).

Tracking the progress of individual students in the experimental class in mastering basic experimentation shows that, for a significant number of students, this learning was still not sufficiently effective. Based on the dynamics of individual progress from the first to the final assessment, we divided the class into three groups:

- Unstable results or lack of progress — 11 students

- Gradual progress under extended task-solving conditions (solving similar tasks with analogous problem structuring) — 4 students

- Quick grasp of the method during the first or second lesson of the topic, followed by consistently correct solutions to similar tasks of equal difficulty using different materials — 14 students

The absence of visible progress in mastering the new method of action did not correlate with lesson absences (Spearman's correlation coefficient r = 0,16; p = 0,426). Apparently, what a student vividly discovers becomes an insight that is effectively learned immediately and firmly retained in memory. Thus, a student from the third group—who attended the first two lessons of the topic but missed the next five—successfully completed the delayed assessment task.

It is likely that the lack of progress observed in many students is related to their insufficient engagement in the learning process. This may be due both to low cognitive motivation and other factors, such as poor comprehension of Russian speech by some children.

Observations of the experimental learning process indicate that a key psychological foundation for understanding the meaning of experimentation—and for being able to plan an experiment based on a hypothesis—is students’ ability to distinguish between experimental and control objects. This involves contrasting and equalizing conditions under which selected objects are placed during joint practical activities. When students fail to draw logical conclusions from comparisons—particularly when this work with conditions has not been properly conducted—it can lead to the development within their logical reasoning system of a new, non-binary way of assessing results. In such cases, answers to experimental questions may be "yes," "no," or "possibly" (Bugrimenko, 2004). This situation often arises when conditions for controlling objects are not precisely organized, making it impossible to confirm or refute hypotheses without conducting additional experiments.

Conclusion

-

The logical-subject matter analysis of experimentation shows that mastering this method of action forms the foundation for understanding causality and clearly distinguishing between temporal and cause-and-effect sequences of events, thus serving as a basis for comprehending educational texts in natural science subjects in secondary school.

-

The logical-psychological analysis indicates that the educational content in primary school can and should be limited to basic experimentation. The essence of this approach involves comparing two objects placed in different conditions based on a tested hypothesis, while ensuring that all other conditions in the experimental and control trials are equalized. This method of action should be distinguished from practical trials, "children's experimentation" (as described by N. N. Poddyakov), demonstration experiments, traditional laboratory work, and scientific experiments.

-

The diagnostic data indicate that mastering basic experimentation falls within the developmental capabilities of younger schoolchildren. However, a teacher's explanation, demonstration, and independent execution of simple experiments—following a ready-made instruction—are practiced in the traditional "World Around Us" course within the School of Russia system (which is used in the vast majority of schools in the country). These methods do not fully ensure an understanding of the meaning of basic experimentation. Regarding the ability to plan a basic experiment, primary school graduates achieve similar results to second-grade students under activity-based learning conditions (Elkonin-Davydov system).

-

The qualitative analysis of the process of forming the method of experimentation shows that the need to simultaneously perform two mutually opposite actions in meaning (contrast and equalization) is the main stumbling block in children's understanding of the new method. This may be related to the failure to distinguish between the goal of the experiment (testing a hypothesis) and the goal of practical influence on an object (achieving a practical effect) (Osterhaus et al., 2016), but this requires further research. It is also necessary to examine how well students differentiate and correlate their experimental plans with the reality of the experiment itself. Additionally, it is important to assess the impact of experimental learning on overcoming Piagetian phenomena that characterize the stage of concrete operations in younger students' thinking.

-

In future research, we plan to examine whether changes in the form of learning (introducing basic experimentation not through a real-world task but in a virtual laboratory (Chudinova, 2022)) influence motivation and the effectiveness of teaching experimentation to children with various learning difficulties.

Limitations. In comparing the results of the final diagnostics, we did not take into account many factors that can influence the results of pupils‘ work, such as, for example, parents’ educational level, teachers' teaching experience, etc. The progress of experimental formation and the dynamics of pupils' work was investigated within the framework of one experimental class, which, of course, requires verification and comparison with the dynamics of learning in other classes using the same methodology.

1 A more detailed description of basic experimentation and the specifics of working with children's hypotheses has been provided in our previous work (Chudinova & Shishkina, 2024).

2 Twenty-four people wrote the final project