Introduction

Emotions represent a complex phenomenon that, in the context of appraisal theories, are viewed as hypothetical constructs (Lazarus, 1993; Roseman, 2001; Scherer, 2003). An emotional response consists of several key components: 1. a cognitive component – evaluating an event; 2. an emotional reaction, which includes sensory, physiological, and motor elements that prepare one for action. Paul Ekman (Ekman, 1999a; Ekman, 2016) was the first to suggest criteria for distinguishing primary emotions from others. Primary emotions include anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. These emotions are identified by universal emotional signals (emotion-specific facial expressions), unique physiological responses, and automatic appraisals consistent with universal emotion-specific antecedents (factors that lead to observable behavior sequences). Other characteristics include typical emergence during development, presence in other primates, rapid onset, short duration, spontaneity, emotion-specific thoughts, memories, imagery, and distinct subjective experiences. According to Ekman, contempt is also classified as a primary emotion. It is noted that evidence supporting the universality of the facial expression of this emotion was gathered from studies involving participants exclusively from civilized cultures who recognized this emotion (Ekman, 1999b; Ekman, 2016). The inclusion of contempt in the list of primary emotions is also reinforced by cross-cultural recognition, despite its recognition rate being the lowest among primary emotions (Elfenbein, Ambady, 2002). Happiness is a positive emotion that most people pursue (Ekman, Friesen, 1975). In contrast, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust are viewed as negative emotions. Surprise is classified as an ambivalent emotion, as it can elicit both positive and negative responses.

Emotions emerged throughout evolution and serve important adaptive and social functions. Oatley and Jenkins (2007) view emotions as the language of social life, a key to understanding the patterns that connect people to one another. As social beings, humans require interpersonal and social relationships: they form groups, cooperate, and establish control over others (Fischer, Manstead, 2008). According to communicative theories (Oatley, Jenkins, 2007), the primary function of emotions is linked to actions that manifest in social interactions (Morris, Keltner, 2000; Van Kleef, De Dreu, Manstead, 2010). Darwin (Kostić, 2010; Kostić, 2014) and his followers (Ekman, 2011) argued that emotions evolved because of their role in preparing the organism for rapid, automatic resolution of vital tasks. This ability is considered a unique mental process with a pronounced social character compared to other cognitive functions (Petrakova, Mikadze, Raabe, 2021).

Numerous studies (Petrović, Mihić, 2009) have shown that emotion recognition begins to develop at an early age (Kuznetsova, Makurin, 2010). A number of empirical studies on the perception of emotions through facial expressions have found that the average accuracy of recognition is around 60% (Ekman, O'Sullivan, Frank, 1999; Howell, Jorgenson, 1970; Kostić, 2010; Kostić, 2014). Kostić’s study (2010) confirmed the reliability of facial expressions as a source of emotional information. The results showed that participants successfully recognized all six emotions included in the experiments (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, surprise). The highest recognition accuracy was observed for happiness, while the lowest was for sadness. Existing data allow us to conclude that facial expressions are a reliable source of information about experienced emotions.

Studying the concept of profession, its key characteristics, and the distinction between helping and non-helping professions is a complex research question. Helping professions are defined as professions aimed at assisting people in solving their life problems. A common feature of all helping professions is personal contact between a client in need and a professional (Ajduković, Ajduković, 1996). Helping professions are those in which a person chooses to act professionally or voluntarily in situations where ordinary forms of mutual aid are insufficient, and additional help and support are required. In contrast, non-helping professions are focused on working with objects and involve a lower degree of interpersonal interaction.

Some authors (Ekman, O'Sullivan, 1991; Ekman, O'Sullivan, Frank, 1999) conducted studies to determine whether the accuracy of emotion recognition through facial expressions depends on one's profession. Participants included members of U.S. intelligence agencies, police officers, judges, psychiatrists, professionals investigating fraud, and psychology students. The data showed that only intelligence agents were able to distinguish between genuine and fake emotional expressions successfully. These results are explained by their professional experience, which involves contact with people from various professions, and the specific training intelligence agents undergo. Similar studies were conducted involving federal officials, sheriffs, judges, legislators, clinical psychologists who focus on clients involved in deception, clinical psychologists without a focus, and academic psychologists. The results showed that sheriffs were the most successful in recognizing signs of deception, which was also attributed to their professional experience. A study conducted in Serbia (Barjaktarević, 2013) investigated the difference in emotion recognition accuracy between police officers, who are in direct contact with people, and engineers, whose work is more object-focused. The results showed that police officers generally recognized primary emotions in micro facial expressions more accurately (AS = 9,13) than engineers (AS = 5,31). These results are explained by differences in the nature of their work. Police officers are frequently in direct contact with people, are expected to detect deception, and are trained accordingly. In contrast, engineers rarely engage with people; their work is centered on objects, which may explain their difficulties in recognizing emotions through facial expressions. Studies on emotion recognition abilities were also conducted on a sample of 49 police officers in Russia (Padun, Sorokko, Suchkova, Lyusin, 2021), as emotion recognition is considered a vital component of their profession. For example, the ability to recognize anger and aggressive intent on others’ faces in a timely manner is crucial for quick reactions in life-threatening situations involving police officers.

Studies on the accuracy of emotion recognition show that the emotion of happiness is recognized with the highest accuracy on the human face (Burgess, Lien, 2022), which is also confirmed when emotions are presented on simplified versions of human faces, such as drawings or emoticons (Kostić, Todić Jakšić, Tošković, 2020). As for professional actors, it is assumed that they express and recognize emotions better than most people because they are trained to portray them convincingly to an audience during their studies. For this reason, researchers conducted a study in which standardized facial expressions were shown to both regular respondents and professional actors who follow the mimetic method and the Stanislavski system. The mimetic method is based on the voluntary movement of facial parts to express emotions. The Stanislavski system relies on reading emotional text, allowing the actor to immerse themselves in a specific emotional context. The results of the study showed a clear trend: professionals using the mimetic method recognized emotions more accurately than regular respondents or respondents using the Stanislavski system. The results of another study support the nativist concept. In this study, 54 psychology students and 54 psychology graduate students with therapeutic work experience participated in identifying facial expressions of emotions and the intensity of those emotions. A standardized database of Caucasian and Japanese faces was used (Matsumoto, Ekman, 1988). The results showed no significant difference in emotion recognition accuracy between the two groups of respondents. However, respondents perceived Japanese faces as more emotional. Additionally, there was a clear tendency for respondents to rate emotions expressed on female faces as more intense than the same emotions expressed on male faces (Hutchison, Gerstein, 2012).

Although numerous studies confirm the superiority of helping professions in accurately recognizing emotions, there are also studies in which experienced professionals demonstrate lower recognition accuracy than non-specialists. One such example is a study (Balda et al., 2000), in which the percentage of correct recognition of pain expressions on infants’ faces was lower among medical professionals compared to a non-medical group composed of parents. This raises the question: does the accuracy of recognizing basic emotional expressions depend on innate predispositions, or does experience play a decisive role? Recent research (Gori, Schiatti, Amadeo, 2021), conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic, confirms the importance of social context in emotion recognition. These findings show a decrease in the accuracy of emotion recognition among respondents aged 3 to 30 when they are unable to see the full face of the interlocutor. The wearing of medical masks led to a general decline in the ability of respondents to recognize others’ emotions based on facial expressions. This effect was especially pronounced among children aged three to five, for whom the decrease in emotion recognition accuracy was most noticeable when comparing masked and unmasked faces. These results emphasize that while there may be innate tendencies in recognizing emotions, the social context also plays a crucial role. A study conducted in Serbia (Pejičić, 2020), which considered variables such as age and level of education, showed that healthcare workers were more successful at recognizing primary emotions through facial expressions than electrical engineers, technologists, and production workers. These findings are explained by the fact that healthcare workers frequently face the need to recognize emotions in the course of constant interaction with patients, whereas engineers, who work with objects, are rarely required to assess the emotions of those around them.

Recent studies (Dietl, Meurs, Blickle, 2016) have primarily focused on identifying the link between emotions and career. The findings confirm that the ability to recognize emotions correlates with several professional indicators and achievements, such as job performance (Elfenbein, Ambady, 2002), successful negotiations (Elfenbein et al., 2007), effective leadership (Rubin, Munz, Bommer, 2005), and income (Mom, Fourné, Jansen, 2015). However, the general conclusion of these studies is that such correlations may be influenced by intelligence (Kranefeld, Blickle, 2020; Kranefeld, Nill, Blickle, 2021; MacCann et al., 2020) and personality traits (Joseph, Newman, 2010).

Facial expressions of emotions belong to a group of rapid facial signals that occur due to the contraction of facial muscles (Elfenbein, Ambady, 2002; Ekman, Friesen, 1975; Kostić, 2010; Kostić, 2014). The universality of these expressions is supported by findings from studies involving individuals with sensory deprivation, newborns, identical twins, monkeys, as well as a number of cross-cultural studies (Kostić, 2010; Kostić, 2014). We noticed that there had been no assessment of the accuracy of facial emotion recognition between university students studying for helping professions and those preparing for non-helping professions. Based on this, the medical profession (Faculty of Medicine – FM), whose representatives are in constant contact with people and must quickly and accurately recognize patients’ emotions, was selected as a helping profession. The engineering profession (Faculty of Technical Sciences – FTS) was selected as a non-helping profession, in which everyday work does not require direct human interaction and is focused on working with objects. Given these factors, we considered it necessary and justified to conduct a study aimed at assessing the ability to recognize emotions depending on the type of professional activity. Our initial hypothesis was that students studying in fields related to helping professions would more successfully recognize emotions based on facial expressions compared to students pursuing non-helping professions.

Since the time of Charles Darwin’s work, it has been known that there is a universal expression of basic facial emotions—that is, their recognition is not dependent on cultural characteristics. Therefore, our study focused only on primary emotions, and the goal was to determine whether there are differences in the accuracy of recognizing basic (universal) facial emotional expressions, independent of cultural factors, between students who chose helping professions and those pursuing non-helping professions.

Materials and Methods

The dependent variable was the accuracy of recognizing facial expressions of seven emotions: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The independent variable was the type of profession, a categorical variable with two levels – helping profession (Faculty of Medicine – FM) and non-helping profession (Faculty of Technical Sciences – FTS).

The sample was representative and consisted of students from the University of Priština temporarily located in Kosovska Mitrovica. In the total sample (145 students of both sexes), 51% of respondents were oriented toward working with people (helping profession – FM), while 49% were oriented toward working with objects (non-helping profession – FTS). The age of the respondents ranged from 19 to 36 years (mean age = 22,88 ± 2,43 years).

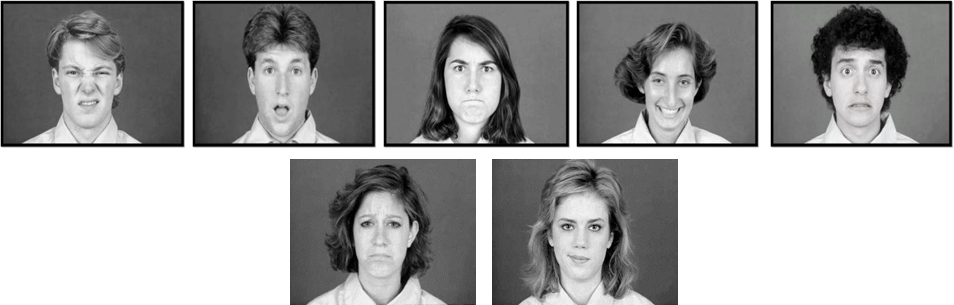

Analyzing the conflicting results of previous research, we proposed a more systematic stimulus control, i.e., selection of standardized facial expressions of emotions, as well as a more homogeneous sample in terms of education and experience. The stimulus material consisted of the Japanese and Caucasian Facial Expressions of Emotion (JACFEE) set (Matsumoto, Ekman, 1988), which includes 56 photographs – eight images for each of the seven emotions: disgust, surprise, anger, happiness, fear, sadness, and contempt (see figure). For each emotion, four photographs featured coders of Asian descent, and the other four featured coders of Caucasian descent (two men and two women in each group). All photographs were coded by Ekman and Friesen (Ekman, Friesen, 1975) using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS), ensuring the validity of the expressions.

The experiment was conducted using the OpenSesame program. The stimuli were presented to the respondents in random order, with the randomization of stimuli automatically handled by the software. The direction of the respondents’ gaze was controlled by displaying a fixation cross in the center of the screen for 100 ms. Respondents were positioned 50 cm from the screen (12.3-inch diagonal, 2736 x 1824 ppi resolution, 120 Hz refresh rate). The stimuli were displayed on the computer screen for an exposure time of 10 seconds. The stimuli were centered on the screen, with a size of 904 x 642 pixels. Respondents were asked to indicate on a sheet of paper which of the seven proposed emotions corresponded to each face. The accuracy of emotion recognition was assessed by calculating the mean value of the participants’ responses.

Results

The hypothesis that students from the helping professions faculty (FM) would be more successful in recognizing emotions compared to students from the non-helping professions faculty (FTS) was tested. Using the t-test, it was found that respondents oriented toward working with people (FM) demonstrated greater accuracy in recognizing facial expressions of emotions compared to respondents oriented toward working with objects (FTS). Specifically, FM students recognized the emotions of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, and surprise significantly more accurately, while FTS students were more successful in recognizing the emotion of happiness (see table). No differences were observed between the two groups in the accuracy of recognizing the emotion of sadness (see Table 1).

Table 1

Differences in the recognition accuracy of facial expressions of emotions between respondents from the Faculty of Medicine (FM) and the Faculty of Technical Sciences (FTS)

|

Emotions |

Occupation |

M (SD) |

t (df = 143) |

p |

|

Anger |

МФ / FM |

6,16 (2,25) |

7,34 |

<0,0001 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

3,52 (2,08) |

|||

|

Contempt |

МФ / FM |

5,12 (3,38) |

5,01 |

<0,0001 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

2,48 (2,95) |

|||

|

Disgust |

МФ / FM |

7,54 (1,78) |

7,71 |

<0,0001 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

4,77 (2,49) |

|||

|

Fear |

МФ / FM |

6,04 (2,92) |

2,58 |

0,011 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

4,92 (2,28) |

|||

|

Surprise |

МФ / FM |

7,61 (1,8) |

3,46 |

0,001 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

6,46 (2,17) |

|||

|

Happiness |

МФ / FM |

6,38 (3,13) |

-2,02 |

0,045 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

7,20 (1,39) |

|||

|

Sadness |

МФ / FM |

6,40 (2,93) |

0,03 |

0,979 |

|

ФТН / FTS |

6,39 (2,06) |

Discussion

As noted by Bryan (2015), one of the key characteristics of helping professions is a high capacity for both verbal and non-verbal communication. He adds that qualities such as active listening, compassion, openness, and honesty are closely linked to empathy, self-awareness, self-respect, patience, and self-discipline. These skills are expected to contribute to more accurate recognition of emotions in others. According to research by Reynolds and Scott (2000), empathy and the ability to perceive and understand the feelings of others are fundamental to quality relationships in the helping professions. Since work in these fields often involves addressing behavioral problems, emotional disorders, and interpersonal conflicts, the role of these professionals centers on active listening and providing support to users in achieving better psychosocial functioning and quality of life (Žižak, 2014). Moreover, the results of our study may be explained by the fact that medical students participate in numerous educational programs that focus on developing non-verbal communication skills, such as body language, facial expressions, and gestures. These programs become particularly important in the context of increasing population migration and the emergence of language and cultural barriers in multicultural and multilingual environments. In such conditions, non-verbal signals can become a crucial tool for overcoming communication gaps and improving mutual understanding between medical professionals and patients (Khoshgoftar, Zohreh, et al., 2024). An additional explanation for the obtained results may lie in the fact that medical students regularly interact with sick individuals and often work in stressful environments. Empirical studies confirm that the emotional state of the observer increases the accuracy of recognizing congruent emotions on the faces of stimuli (Lyusin, Kozhukhova, Suchkova, 2019; Nikitina, 2021).

However, an unexpected finding was that students from the Faculty of Technical Sciences (FTS), who are oriented toward working with objects, were more successful in recognizing the emotion of happiness compared to students from the Faculty of Medicine (FM), who are oriented toward working with people. This finding is particularly noteworthy considering that happiness and sadness are traditionally regarded as opposite poles within the basic dichotomy of primary emotions. Upon a more detailed analysis of the data, we found that respondents from both groups were equally successful in recognizing the emotion of sadness. However, when it came to recognizing happiness, FTS students, albeit slightly, statistically significantly outperformed FM students. This may indicate that the lack of live interpersonal interaction limits the development of social skills and the ability to accurately recognize emotions. One possible explanation for the observed differences in recognizing happiness could be the frequency of emoticon use in communication. Emoticons have become an integral part of digital communication and are widely used to express emotions and clarify the meaning of text messages. Previous research has shown that emoticons are more frequently used to convey positive emotions (Zuhdi, Ahmad, et al., 2024). Our data also support this trend, which may explain the FTS students’ higher ability to recognize happiness. Supporting our findings, previous studies have shown that police officers are worse at recognizing the emotions of anger, sadness, and fear than they are at recognizing happiness. Thus, working with facts rather than with people may reduce the accuracy of recognizing negative emotions (Padun, Sorokko, Suchkova, Lyusin, 2021). At the same time, frequent interaction with patients during medical training has made medical students more successful in recognizing negative emotions. In contrast, the absence of a need for detailed analysis of facial expressions in object-focused professions such as engineering may have allowed FTS students to better recognize happiness. Therefore, this study opens up prospects for further research, in which, in addition to analyzing response accuracy, researchers could measure response time. This would allow for the collection of additional data that could significantly deepen our understanding of differences in the perception of basic emotions.

The results obtained suggest the need to develop the ability to recognize emotions through facial expressions, especially among individuals who do not have the opportunity for direct contact with clients in their profession. Thus, individuals who choose helping professions demonstrate a higher level of recognition of basic emotions through facial expressions compared to those who choose non-helping professions. This can be achieved through a range of programs aimed at developing emotional abilities and skills, which include: 1. the ability to quickly notice, assess, and express emotions; 2. the capacity to swiftly perceive and generate feelings that facilitate cognitive processes; 3. the ability to understand emotions and possess knowledge about them; 4. the ability to regulate emotions in order to promote emotional and intellectual growth. Many authors have noted the positive effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) on emotional regulation through the use of cognitive restructuring techniques (Gilboa-Schechtman, Azoulay, 2022).

Conclusion

Facial expressions of emotions represent complex behavioral responses that require a high level of attention and accuracy for correct interpretation (Ekman, 2011). The results of conducted studies show that facial expressions of basic emotions can be interpreted with a high degree of accuracy regardless of race, gender, age, and cultural background.

A study conducted on a student sample in Serbia (Pejičić, 2020) confirms findings obtained in other countries, indicating the stability of the ability to recognize emotions through facial expressions depending on one's profession. Our results show that students from medical and technical faculties are almost equally successful in recognizing only two basic emotions—sadness and happiness. However, emotions such as anger, contempt, disgust, fear, and surprise are recognized significantly more accurately by medical faculty students than by their counterparts from the Faculty of Technical Sciences.

Limitations. A limitation of this study is the sample size. In future studies, it is recommended to expand the sample to include students from other helping professions (psychologists, teachers, social workers) and students from other non-helping professions (architects, economists).