Introduction

In the modern world, the problems of social adaptation become more acute at all ages. It becomes particularly relevant at the primary school age, when the social environment of primary school pupils is differentiated and stratified. Yu.V. Gromyko, A.A. Margolis and V.V. Rubtsov note the complexity and ambiguousness of the social environment in their studies: “…challenges and risks of modern society, …are provoked by the rapid disintegration of existing social institutions and established communities, the intensive process of functioning and forming new types of communities and activities. The need to live in a changing and ambiguous social environment presents the individual with a problem of simultaneously being involved in different types of activities and social communities, i.e. with the task that he/she did not face so clearly at previous stages of society development” [Gromyko, 2020, p. 58]. However, environmental factors influencing social adjustment cannot be considered without taking into account the learner’s personality: “Nature and society give every child the opportunity for individual development within overall human development. Every child gradually “learns” to be a human. This “learning” occurs in the context of culture and education. L.S. Vygotsky wrote that each person’s life path is always the interaction of a developmental series: natural (organism’s development) and social (individual’s acquisition of culture)” [Dubrovina, 2017, p. 45]. These provisions are reflected in school standards: “The school standards outline the qualities of schoolchildren’s personality that should be formed in the learning process: a responsible attitude to learning; the readiness and ability for self-development, self-education; a conscious, respectful and benevolent attitude towards another person; mastering social norms and rules of behavior; developing moral awareness; developing communicative competence, etc. Developing these qualities is defined as the essence of the central line of a pupils’ growth: the mastery of the object world and with the world of relations with the social reality, of the environment, and of the inner self” [Dubrovina, 2021, p. 52].

Modern research has analyzed the concept of adaptation: “…the concept of adaptation can be interpreted not only as a process of adjustment to external changes for the sake of homeostatic maintenance, but also as the end result of the development of special skills and abilities necessary for a child’s normal and successful existence and development” [Egorenko, 2016, p. 59]. In F.B. Berezin’s works “adaptation processes are considered as a comparison of the social (educational) environment and the learner’s personality. This allows the latter to meet his educational needs and compare them with the requirements of the environment” [Egorenko, 2016, p. 59]. Thus, both the social environment and the learner’s personality formed in this environment influence adaptation success.

Difficulties in adjusting socially can become apparent when children start schooling. As stated in the “System of Psychological Services’ functioning in general educational organizations” methodological recommendations: “At school the following are evident: weak links in the structure of the cognitive and emotional sphere; unformed arbitrary behavior forms — an insufficiency of self-regulation; immaturity of motivational formations; inability to assimilate group norms, school maladaptation (pupil’s internal position); reduction of psycho-emotional well-being” [Sistema funktsionirovaniya psikhologicheskikh, 2020, p. 54].

According to the general classification of learning difficulties developed within the framework of the “Development and Testing of the Target Model of the System of Prevention and Correction of Learning Difficulties in Pupils with Relevant Risks of Unfavorable Social Conditions” project in the sphere of social adaptation, learning difficulties can be classified into the following types: deviant behavior, social maladaptation, psycho-emotional handicap, which manifests itself at the stage of primary school in difficulties in adapting to the rules of school life, the need for increased attention to oneself, or suspicion, tension, isolation, rejection in class, a lack of strong friendships with classmates, profanity, aggressive actions towards others.

Modern psycho-pedagogical practice has a number of psycho-diagnostic techniques aimed at identifying difficulties in various aspects of social adaptation. A special diagnostic program for the purpose of the psychological and pedagogical diagnostics of learning difficulties in 4th grade students in various spheres was developed within the "Development and Testing of the Target Model of the System of Prevention and Correction of Learning Difficulties in Students with Relevant Risks of Unfavorable Social Conditions" project. The developed diagnostic program will allow for the timely identification of emerging problems in the social adaptation of students. In turn, it will allow specialists to effectively build psychological and pedagogical interaction [Programma diagnostiki trudnostei, 2022]. In 2020, Moscow State University of Psychology and Education together with the Institute of Education of the Higher School of Economics developed a model of the system of preventing and correcting learning difficulties in students. According to the authors of the model - E.I. Isaev, S.G. Kosaretsky and Y.P. Koroleva: "The core of the developed target model is the model of individualization of pedagogical activity in work with learning difficulties, which implies the use of three gradually deepening stages of individualization of learning, including a number of obligatory forms of organization of such work: individual planning within the framework of main classes, additional teaching in small groups and individual classes, psychological correction of detected psychological deficits" [Isaev, 2022, p. 22]. Thus, the issues of the early identification of learning difficulties are key for organizing effective psychological-pedagogical prevention.

This paper presents the results of a study of learning difficulties in the field of social adaptation in primary school children in accordance with the manifestations of these difficulties.

Research Procedure

Purpose. To identify the predominant learning difficulties in the field of social adaptation in primary school children.

Sample. The study involved 2030 students (51 % male) aged 9 to 11 years old (mean age = 10.0 ± 0.4 years) from different regions of the Russian Federation: the Republic of Tatarstan (20.5 %), Lipetsk Region (16.5 %), Volgograd Region (20.0 %), the Chuvash Republic (22.4 %), and Samara Region (20.5 %).

Methods. Three methods have been used to diagnose learning difficulties in the area of social adjustment: Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), which allows to assess behavior, the emotional sphere and relations with peers [16, 17, 18], the Dembo-Rubinstein method of self-esteem and the level of aspiration measurement modified by A.M. Prihozhan [Prikhozhan, 1988, p. 110] and Taylor’s Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (CMAS) adapted by A.M. Prihozhan [Prikhozhan, 2000, p. 233].

The study was conducted sequentially in a computerized form in groups of 12 to 20 people simultaneously for all the methods presented. The test lasted no more than 40 minutes. Parents gave informed consent for their child to participate in the study. The empirical data was collected between September 2022 and April 2023.

Statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were used to present the results. Student's t-test was used to compare the groups of boys and girls. Cohen's d was calculated to estimate effect size. To compare groups of students of different sex with different levels of the total number of problems (normative, borderline and deviant) on the subscales of Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (CMAS) a three-way ANOVA with the Duncan post hoc test was used, and on the subscales of Dembo-Rubinstein’s method of self-esteem and level of aspiration measurement a four-way ANOVA with the Duncan post hoc test was used.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the scales of Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and Dembo-Rubinstein’s method of self-esteem and level of aspiration measurement for the whole sample and separately for boys and girls are presented in Table 1. The results of SDQ show that, on average, students aged 9-11 years old score within the norm on the prosocial behavior and hyperactivity / inattention scales, while scores on emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer relationship problems are slightly above the norm. As a result, both boys and girls show scores much closer to borderline (15 points) than to normal (up to 14 points) on Total difficulties score. Meanwhile, girls have more emotional problems, and boys have problems with peers.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics (mean ± standard deviation) for the Methods of Measuring Social Adaptation: Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Dembo-Rubinstein Method of Self-Esteem and Level of Aspiration Measurement

|

Subscale |

Whole sample N = 2030 |

Girls N = 994 |

Boys N = 1036 |

Norm |

|

Prosocial behavior* (d=0.16) |

7.8 ± 2.0 |

7.9 ± 2.0 |

7.6 ± 2.0 |

6-10 |

|

Hyperactivity / inattention |

3.2 ± 2.3 |

3.2 ± 2.2 |

3.3 ± 2.3 |

0-5 |

|

Emotional symptoms* (d=0.29) |

3.2 ± 2.6 |

3.6 ± 2.6 |

2.9 ± 2.5 |

0-3 |

|

Conduct problems* (d=0.15) |

2.7 ± 1.9 |

2.6 ± 1.8 |

2.8 ± 1.9 |

0-2 |

|

Peer relationship problems* (d=0.22) |

3.3 ± 2.0 |

3.0 ± 2.0 |

3.5 ± 2.1 |

0-3 |

|

Total difficulties score |

12.4 ± 6.4 |

12.4 ± 6.5 |

12.4 ± 6.4 |

0-14 |

|

Dembo-Rubinstein’s Method of Self-esteem and Level of Aspiration Measurement: Self-esteem |

||||

|

Health |

7.5 ± 2.0 |

7.5 ± 2.0 |

7.5 ± 2.0 |

4.5-7.4 |

|

Intelligence |

7.3 ± 2.0 |

7.3 ± 2.0 |

7.3 ± 2.0 |

|

|

Character* (d=0.10) |

7.3 ± 2.1 |

7.4 ± 2.1 |

7.2 ± 2.1 |

|

|

Credibility |

7.1 ± 2.2 |

7.1 ± 2.2 |

7.0 ± 2.3 |

|

|

Ability* (d=0.26) |

7.3 ± 2.2 |

7.6 ± 2.2 |

7.0 ± 2.3 |

|

|

Appearance* (d=0.13) |

7.6 ± 2.3 |

7.7 ± 2.2 |

7.4 ± 2.3 |

|

|

Self-confidence |

7.3 ± 2.3 |

7.2 ± 2.3 |

7.4 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Average level of self-esteem* (d=0.09) |

7.3 ± 1.5 |

7.4 ± 1.5 |

7.3 ± 1.5 |

|

|

Dembo-Rubinstein’s Method of Self-esteem and Level of Aspiration Measurement: Level of Aspiration |

||||

|

Health* (d=0.10) |

8.3 ± 2.1 |

8.4 ± 2.1 |

8.2 ± 2.2 |

6.0-8.9 |

|

Intelligence |

8.3 ± 2.1 |

8.4 ± 2.1 |

8.2 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Character* (d=0.17) |

8.0 ± 2.2 |

8.2 ± 2.1 |

7.9 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Credibility* (d=0.14) |

8.1 ± 2.2 |

8.3 ± 2.1 |

8.0 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Ability* (d=0.21) |

8.3 ± 2.1 |

8.5 ± 2.0 |

8.0 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Appearance* (d=0.24) |

8.5 ± 2.1 |

8.7 ± 1.9 |

8.2 ± 2.1 |

|

|

Self-confidence* (d=0.10) |

8.4 ± 2.1 |

8.5 ± 2.1 |

8.3 ± 2.2 |

|

|

Average level of aspiration* (d=0.19) |

8.3 ± 1.7 |

8.4 ± 1.6 |

8.1 ± 1.7 |

|

Note: * statistically significant differences at the level of p<0.05 by Student's t-test are marked, Cohen's d is given in brackets.

The results of the self-esteem and aspiration measures show that almost all indicators are within the norm, but tend to be high (Table 1). The differences between boys and girls are small, as the effect size in no case reaches the medium (d<0.3). In the younger school age, the leading activity gradually changes; the immersion in a new social development situation requires the primary school child to be active. Numerous activities constantly place the primary school child "in situations in which he/she must somehow relate his/her abilities to himself/herself, evaluate his/her activity, think about how to act in the future" [Samylova, 2016, p. 166], which in turn contributes to the formation of self-esteem.

Descriptive statistics on the scales of Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (CMAS) for the whole sample and separately for boys and girls and for the ages of 9 and 10-11 are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics (mean ± standard deviation) for the Method of Measuring Social Adaptation “Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale” (CMAS), Adapted by A.M. Prihozhan

|

Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (CMAS) |

|||||

|

Subscale |

Measurement results |

Norm |

|||

|

Whole sample N = 206 |

Girls N = 107 |

Boys N = 99 |

Girls |

Boys |

|

|

9 years |

|||||

|

Social Anxiety* (d=0.41) |

5.2 ± 2.5 |

5.7 ± 2.6 |

4.7 ± 2.2 |

- |

- |

|

Defensiveness |

4.7 ± 2.5 |

5.0 ± 2.5 |

4.5 ± 2.6 |

- |

- |

|

Physiological Anxiety* (d=0.32) |

2.7 ± 2.3 |

3.0 ± 2.4 |

2.3 ± 2.3 |

- |

- |

|

Worry* (d=0.30) |

5.4 ± 2.4 |

5.8 ± 2.3 |

5.1 ± 2.4 |

- |

- |

|

Anxiety (total score)* (d=0.38) |

18.1 ± 8.0 |

19.5 ± 8.1 |

16.6 ± 7.6 |

4-19 |

5-17 |

|

10-11 years |

|||||

|

Subscale |

Measurement results |

Norm |

|||

|

Whole sample N = 1824 |

Girls N = 887 |

Boys N = 937 |

Girls |

Boys |

|

|

Social Anxiety* (d=0.27) |

5.3 ± 2.9 |

5.7 ± 3.0 |

4.9 ± 2.8 |

- |

- |

|

Defensiveness* (d=0.19) |

4.9 ± 2.7 |

5.2 ± 2.7 |

4.6 ± 2.6 |

- |

- |

|

Physiological Anxiety* (d=0.11) |

3.0 ± 2.3 |

3.1 ± 2.3 |

2.9 ± 2.3 |

- |

- |

|

Worry* (d=0.35) |

5.3 ± 2.6 |

5.7 ± 2.6 |

4.8 ± 2.5 |

- |

- |

|

Anxiety (total score)* (d=0.28) |

18.4 ± 9.0 |

19.7 ± 9.0 |

17.2 ± 8.8 |

8-21 |

7-20 |

Note: * statistically significant differences at the level of p<0.05 by Student's t-test are marked, Cohen's d value is given in brackets.

Analysis of the results shows that 9-year-old girls have anxiety scores slightly above the norm, while 9-year-old boys are within the norm. Thus, girls are more anxious (the effect size is medium) and this is mainly due to higher social anxiety (Table 2, d=0.41). At age 11, both girls' and boys' anxiety scores level off and are within the normative range, but girls' anxiety scores are higher and on average exceed boys' anxiety scores by 2.5 points (the effect size is medium).

When comparing anxiety scores between girls and boys, differences were found for all measures of anxiety, but for the “Defensiveness” and “Physiological Anxiety” scales they are minimal: statistical effects are either insignificant or small.

More detailed statistics on the number and percentage of pupils with different levels of problems in different areas of their lives are given in Table 3 (Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for measuring social adaptation). The results show that peer relationship problems (almost half of the children – 42.9% - have them) and behavioral problems (about one third of the children – 30.7% - have them) are most common at this age.

Table 3. Intensity Levels for the Scales of Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire:

Number of People / Percent

|

Subscale |

Subscale Intencity |

||

|

Normal |

Borderline |

Deviant |

|

|

Prosocial behaviour* |

1723 / 84.9 % |

145 / 7.1 % |

162 / 8.0 % |

|

Hyperactivity/inattention |

1706 / 84.0 % |

160 / 7.9 % |

164 / 8.1 % |

|

Emotional symptoms* |

1633 / 80.4 % |

153 / 7.5 % |

244 / 12.0 % |

|

Conduct problems* |

1406 / 69.3 % |

267 / 13.2 % |

357 / 17.6 % |

|

Peer relationship problems* |

1160 / 57.1 % |

565 / 27.8 % |

305 / 15.0 % |

|

Total difficulties score |

1379 / 67.9 % |

335 / 16.5 % |

316 / 15.6 % |

To test the effect of behavioral problems on other indicators of social adjustment, three groups of children (with normal, borderline and deviant values on Total difficulties score (SDQ)) were compared on self-esteem and aspiration.

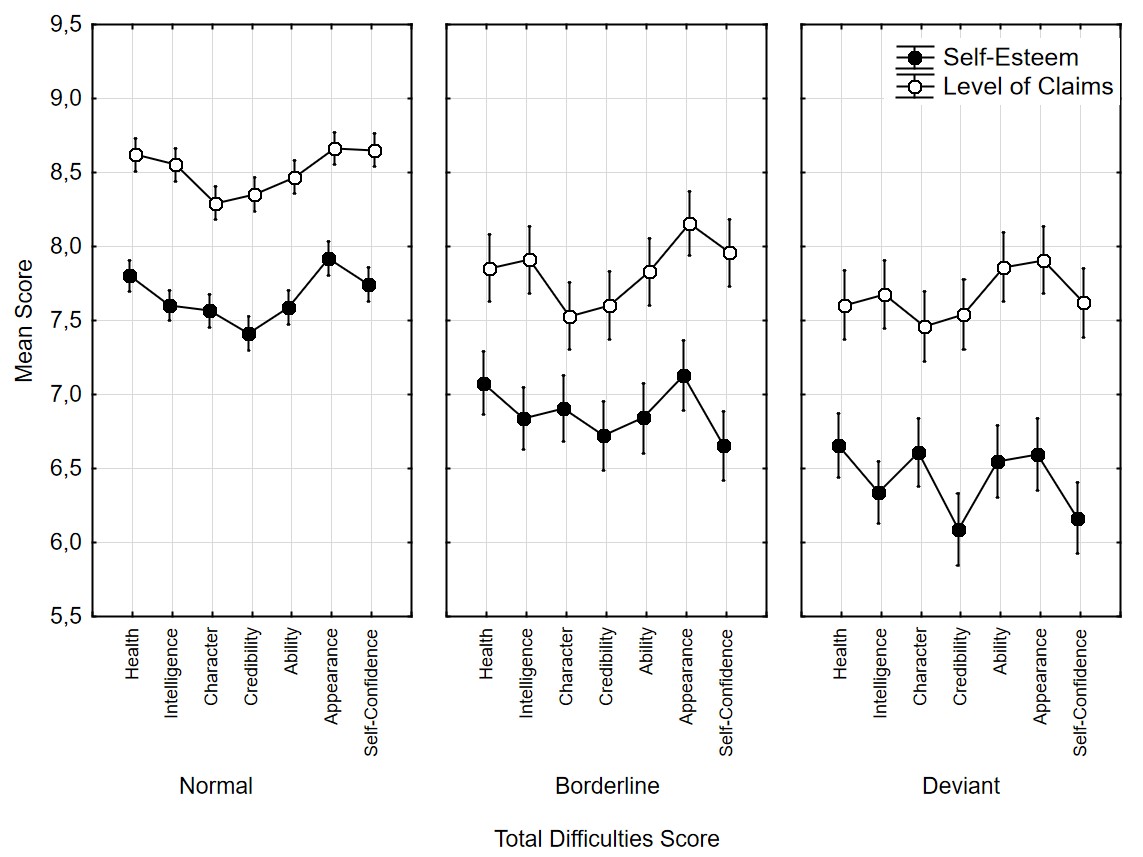

A four-way ANOVA showed that the third-order interaction Sex*Group*Self-esteem*Aspiration was not statistically significant (F(12, 12144)=1.2; p=0.27), whereas the second-order interaction Group*Self-esteem*Aspiration was significant (F(12, 12144)=2.6; p=0.0016). This means that the relationship between the ratio of self-esteem and the level of aspiration depends on the number of difficulties and is same for both boys and girls. Fig. 1 shows the mean values of self-esteem and the levels of aspiration for the three groups of students. Children with a minimum number of problems have a slightly inflated self-esteem (7.5-8.0 points) and an optimal level of aspiration (8-9 points, which is an important factor in personal development). Differences between self-esteem and aspirations rarely exceed 1 point, indicating that these children set goals that they can achieve. Their aspirations are based on self-esteem and serve as a stimulus for personal development. It should also be noted that the differentiation of both self-esteem and the level of aspiration is the lowest in this group.

The level of self-esteem (average) and the level of aspiration (average) are much lower in children with borderline scores on the total number of problems. At the same time, the gap between the levels of self-esteem and aspiration increases, and the differentiation in aspiration reaches its maximum value. The discrepancy between self-esteem level and aspiration level indicates that the aspirations not only do not contribute to personal development, but can significantly slow it down. The gap between self-esteem and aspiration is even greater in children with deviant values of the total number of problems. This indicates an emerging conflict between what a child aspires to and what he or she thinks is possible. Children in the third group have the most differentiated self-esteem. Pupils with low, highly differentiated self-esteem usually have a strong sense of insecurity and a strong desire to understand themselves and their abilities. We believe that this situation indicates the formation of self-esteem, restructuring it.

Fig. 1. The relationship between self-esteem and the level of aspiration (means and 95% confidence interval) for three groups with different scores on the Total difficulties score:

normative, borderline and deviant.

Similar analysis was performed for the Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (CMAS). A three-way ANOVA showed that the second-order interaction Sex*Group*Anxiety_Factors was not statistically significant (F(6, 6072)=0.3; p=0.96), whereas the second-order interaction Group*Anxiety_Factors was significant (F(6, 6072)=14.5; p<0.00001). This means that the relationship between Manifest Anxiety Scale subscales depends on the number of difficulties and this relationship is the same for boys and girls. Fig. 2 shows the means for all subscales for the three groups of students.

Fig. 2. Anxiety Subscales (Mean Values and 95% Confidence Interval) on Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale for Three Groups with Different Values of the SDQ Total difficulties Score:

Normative, Borderline and Deviant

The results suggest that children in the group with a normal number of problems have the lowest levels of manifest anxiety. The borderline and abnormal problem groups differ from them on all scales, and they in turn differ on the scales of Social Anxiety and Physiological Anxiety. At the same time, there are no statistically significant differences in Defensiveness and Worry (according to Duncan's post hoc test, p=0.12 and p=0.48).

Discussion

As a result of the qualitative and quantitative analyses of the empirical data obtained, the main learning difficulties in the area of social adaptation of primary school pupils were identified.

It was found that the most typical difficulties for primary school boys are difficulties in establishing cooperative or friendly relationships with peers, the rejection by peers, aggressiveness towards others, irritability, a difficulty or unwillingness to follow behavioral rules. In girls of primary school age, difficulties of an emotional nature predominate, i.e. they are more exposed to stress and its manifestations, anxieties and fears, and girls are more prone to manifestations of voluntary behavior for the benefit of another person and society as a whole, adherence to generally accepted rules, attentiveness towards others. Difficulties in establishing cooperative or friendly relationships with peers and the rejection of peers are more prominent in boys of primary school age. These results are consistent with the study of E.V. Slavutskaya, according to whom the difficulties in learning include "social infantility and emotional immaturity...", and in boys "low dominance and openness to interpersonal contacts" [Slavutskaya, 2011, p. 5]. Prosocial behavior is more expressed in girls, which, in our opinion, is explained by the fact that "women express emotions better and are more sensitive to the feelings of others (are empathic) than men" [Kukhtova, 2004, p. 70], although this effect is not pronounced (Cohen's d <0.2). These results are consistent with the results of the study by V.N. Burkova, M.L. Butovskaya, D.A. Dronova and Y.I. Adam, who showed that "girls are distinguished by more pronounced prosociality in decision making in relation to unfamiliar peers" [Burkova, 2021, p. 61-62].

Both girls and boys of primary school age are characterized by an optimal representation of their abilities, beliefs about themselves, self-esteem, while there is a tendency for them to be unable to set goals, correctly assess the results of their activities, compare themselves with others. Social anxiety, worry and defensiveness are more common in girls of primary school age. The number of difficulties in the social sphere depends on the relation between self-esteem and the level of aspiration: the least number of difficulties is shown by children with slightly exaggerated self-esteem and an optimal level of aspiration, and with a minimal gap between them. An increase in the gap between self-esteem and the level of aspiration contributes to behavioral problems in younger pupils: the conflict between what a child aspires to and what he or she thinks is possible contributes to a number of difficulties. The obtained results are consistent with the results presented in contemporary studies. For example, L.V. Semina in her study "Features of the Level of Primary School Children's Aspirations in Learning Activities" notes the normativity, but at the same time the instability of primary school children’s aspirations. The author also notes that pupils of the 4th grade have a higher level of aspiration than pupils of the 1st grade and that "the formation of a pupil's level of aspiration at the lesson determines ... the confrontation of personal and social determinants (first of all, the value orientations of the class and reference groups)" [Semina, 2003, p. 19].

For the entire group of pupils, the anxiety indicators normalize by the age of 11. However, the anxiety indicators of girls are higher and, on average, 2.5 points higher than the anxiety indicators of boys. These results are in line with the findings of V.M. Rudomazina's research: "Up to the age of 11, anxiety indicators decrease, and a high level of anxiety is not found in children of this age" [Rudomazina, 2016, p. 80]. Also, in A.M. Prihozhan’s research it is noted that during the age of 8-10 years old anxiety indicators are stable, and at 11 years old anxiety indicators increase [Prikhozhan, 2000]. Anxiety indicators are slightly higher than normative values for 9-year-old girls and - within the norm - for 9-year-old boys, which is in accordance with the results of the research of A.M. Prihozhan, who notes higher anxiety indicators for girls [Prikhozhan, 2000], which, in our opinion, is reflected in the normative values of A.M. Prihozhan’s questionnaire. At the same time, the obtained results do not agree with the results of the research of V.M. Rudomazina, who notes higher values of anxiety in girls in the first and fourth grades, and in boys in the second and third grades [Rudomazina, 2016, p. 83].

Conclusion

This study is the result of pilot testing of one of the psychodiagnostic blocks of the “Program for Diagnosing Primary School Students’ Learning Difficulties in the Communicative Sphere and Social Adaptation, in the Sphere of General Academic and Universal Actions” and an attempt to supplement the current empirical data based on the classification of learning difficulties of students with relevant risks of unfavorable social conditions. This typology is developed in the framework of a unified approach to the educational process as a whole.

The results show that the main difficulties in the area of social adaptation are difficulties in establishing cooperative or friendly relationships with peer groups, peer rejection, aggression towards others, irritability, the difficulty or refusal to follow behavioral rules, emotional difficulties, difficulties in goal-setting, and difficulties in assessing the results of one’s own activities and comparing one’s self with others. Simultaneously, emotional problems are more pronounced in girls and peer and behavioral problems in boys.

It has also been found that the conflict between what a child wants to achieve and what he or she thinks is possible, as well as anxiety level contribute to problems relating to peers and behavior.

Research Limitations and Perspectives

While conducting this study some difficulties and limitations emerged. We believe that one of the main limitations is the insufficient number of standardized, valid and adapted psychodiagnostic methods for specific manifestations of difficulties in the selected area, with the possibility of using them in a computerized version with primary school children. The manifestations of learning difficulties in the area of social adaptation are much more diverse than those presented in this study and may be related not only to individual characteristics, but also, for example, to the situation in the family, educational context, etc. This polymorphism complicates the research process and makes it necessary to take into account the maximum number of manifestations of learning difficulties in the area of social adaptation when analyzing the results.

These limitations can also be considered directions or "growth points" for further research in this area.