Introduction

Implementation of inclusive education in Russia offers the opportunity to study the main obstacles to the development of inclusive practices through a systemic perspective. One of these obstacles is the continuation of inclusive practices at the general and vocational education levels. The Federal Law “On Education in the Russian Federation” states that the continuity concept must be applied at all educational levels. According to the law, Article 10 states in paragraph 7 that “The education system shall provide conditions for uninterrupted education...” [Federal'nyi zakon Rossiiskoi] Persons with special educational needs will also benefit from the implementation of education continuity under the inclusive education concept outlined in the law on education (art. 2, para. 27). This concept is founded on the principles of equality and respect for all types of special educational needs.

Special educational needs must be respected to ensure inclusive education continuity, which is widely acknowledged as the concept of “education for all” [Inchkhonskaya deklaratsiya “Obrazovanie-2030; Organizatsiya Ob"edinennykh Natsii], including for students from ethno-cultural minorities, gifted students, students with migrant backgrounds and non-native languages of learning, students with disabilities and health limitations1, and other learners [Kondrat'ev, 2012; Khukhlaev, 2015; Dobson, 2024; Lindner K.-T, 2023; Schwab, 2021; Travaglini, 2024; Zaķe, 2010].

1 The term “students with health limitations” is used as an equivalent to the internationally used term “students with disabilities” because the Russian educational system distinguishes two concepts: “a student with disabilities” is someone who has a medical condition that makes them disabled, while “a student with health limitations” is someone who needs special conditions to be successful in learning.

Education continuity is only possible if all citizens are granted an opportunity and right to receive any type of education and “follow an individual educational path’ according to their needs, demands, and abilities” [4, с. 22]. Since it is no longer seen as a goal but rather as a chance to obtain a career and lead an independent life, one of the primary goals of inclusive education and its quality indicators is to create an individual educational path for people with special needs from early care to vocational education [Rubtsov, 2019].

According to the continuity principle, the inclusive education environment (IEE) must be flexible, adjustable, and variable, and it must be possible to change it to accommodate each learner’s unique needs and individual educational path (IEP). For effective self-development at an educational institution (EI), the IEE ought to offer all learners the chance to receive high-quality education [Alekhina, 2022; Yasvin, 2019].

The article’s objective is to present data that illustrate the degree of inclusive process continuity in general and vocational education in Russia using a set of indicators that demonstrate how well the system can accommodate an individual’s need to complete an educational path while taking into account their abilities.

This article analyses data from general and secondary vocational education levels using the four basic indicators of inclusive process continuity. These indicators include: 1) ensuring that educational plans, programs, and organizational teaching styles are diverse; 2) offering pedagogical and psychological support to learners with special educational needs and its staffing; 3) ensuring that all learners and their parents participate in the educational process and in the educational institution’s activities; and 4) helping learners make their own decisions and choose a professional education path.

Methods

A research team from the Federal Resource Centre for the Development of Inclusive General and Additional Education conducted the research in 2023.

Sampling: Respondents were chosen at random from 6,377 educational institutions spread throughout 82 regions of the Russian Federation, which accounts for 15% of the whole EI network. The organization of the sampled population mirrored that of the broader population. Three sets of respondents (6,377 heads of educational institutions, 60,870 teachers, 92,093 parents, and 32,039 secondary vocational education (SVE) students) were included in the sample’s quantitative data.

Methods: frequency analysis of the obtained data; “IEE monitoring” (automated information system) — for data collection and processing; AnketologBox software — for questionnaires customization and editing.

Findings of the study Learners with special educational needs

As one of the inclusion development concepts, diversity of learners’ special educational needs [Inchkhonskaya deklaratsiya “Obrazovanie-2030] forms the foundation for the educational system creation and the establishment of an inclusive learning environment. This raises the issue of how to categorize variety. Therefore, as part of inclusive education implementation, we will briefly address this topic before looking at the samples of learners with special educational needs.

There are currently two opposing trends under discussion. The ideology of inclusion, on the one hand, is based on the social definition of disability, which challenges classification as a way to stigmatize and marginalize individuals based on their distinctive qualities. However, this should be avoided when developing an inclusive culture where educational institutions focus on providing all learners with a sense of belonging [Ydesen, 2024]. On the other hand, the state education policy sets education standards that define knowledge and skills requirements for graduates from educational institutions. It also specifies assessment tools that evaluate learner’s capabilities and respective methods for their classification. The second approach aims to preserve learner categories as means to improve the learning process that considers specific features of each learner while ensuring conditions for special education [Karabanova, 2019; Hornby, 2015; Kauffman, 2020]. These two approaches to classification need a careful analysis of the specific features of the general education groups of learners (Tab. 1) that were defined by a wide variety of special educational needs.

The findings of the study reveal that as learners with health limitations advance from one educational level to the next, their degree of inclusion declines significantly: it drops by roughly 3.5 times when they move from preschool to school and by roughly 2 times when they transition from school to a secondary vocational institution. Both their removal from the school system and their transfer to secondary vocational training institutions may contribute to the dramatic drop in the percentage of learners with health limitations as they move onto high school.

The number and percentage of learners with disabilities in the pool increase from 9,026 (1.43%) to 24,612 (1.48%) when they transition from the preschool to school education. At the secondary vocational education level, the percentage of learners with disabilities decreases by more than twice, to 3,729 (0.61%).

At the transition from preschool to school, the percentage of gifted learners rises roughly by 15 times, and at the SVE level, it falls drastically. Similar but less pronounced shifts occur in the percentage of learners whose native language differs from that of teaching.

The percentage of learners with severe speech impairments, ASDs, musculoskeletal disorders, and deaf learners declines substantially as they move from preschool to school, according to the data of inclusion of various categories of learners with health limitations. This could suggest a system barrier to maintaining continuity of an individual educational path for learners with those types of health limitations in inclusive education. However, most visually impaired, hearing impaired, late deafened, and mentally retarded learners transfer to basic school after finishing elementary school, which suggests a rela

Table 1. Percentage of learners with special educational needs at different levels of education in the Russian Federation

|

Category |

PSEI |

GEI |

SVE |

|

Learners with HLs* |

12.25% |

3.99% |

2% |

|

Learners with disabilities* |

1.43% |

1.48% |

0.61% |

|

Gifted learners* |

0.56% |

8.56% |

0.41% |

|

Learners whose mother tongue is different from the main language of teaching* |

3.92% |

8.05% |

1.43% |

|

Deaf learners** |

0.08% |

1.38% |

1.50% |

|

Hearing impaired and late-deafened persons** |

0.29% |

0.47% |

3.89% |

|

Blind learners** |

0.01% |

0.02% |

0.08% |

|

Visually impaired learners, learners with amblyopia, strabismus** |

2.12% |

1.35% |

1.59% |

|

Learners with severe speech impairments** |

75.56% |

10.58% |

0.60% |

|

Learners with musculoskeletal disorders** |

1.71% |

3.41% |

5.0% |

|

Learners with mental retardation** |

12.97% |

60.23% |

– |

|

Learners with ASDs** |

2.34% |

4.15% |

1.36% |

|

Learners with mental deficiency, intellectual disability (ID)** |

1.08% |

21.23% |

84.14% |

|

Learners with severe multiple developmental disorders** |

0.61% |

– |

1.80% |

|

Learners who have undergone cochlear implantation** |

0.13% |

||

tively more steady retention of these learners groups in schools as they move through the educational system.

However, a significant percentage of learners with intellectual disabilities also remain in regular schools (21.2% of learners with health limitations). Their percentage in the SVE (84.1% of learners with health limitations) suggests that they most likely continue their education in the SVE system after that.

Thus, the analysis of the pool of learners with special educational needs, including learners with health limitations, at different levels of education shows drastic changes in the percentage of inclusion of different categories of learners with special educational needs in educational institutions when they move from level to level. It is necessary to investigate both the causes of that dynamics as well as the ways to ensure quality and continuity of education for learners with special educational needs in regular education.

Ensuring diversity in plans, programs, and teaching methods

Due to the diversity of learners at inclusive educational institutions and the necessity to accommodate their educational needs, it is necessary to consider each learner’s distinctive capabilities and offer adaptable learning environments. Individual learning plans (ILPs), adapted basic general education programs (ABEPs), and a variability of teaching techniques are some of the main methods used by the Russian educational system to address the various educational needs of different learners [Federal'nyi zakon Rossiiskoi]. The ILP partially ensures an individualized approach to education for every learner [Menchinskaya, 1971; Federal'nyi zakon Rossiiskoi], whereas adjusted programs variants implement the differentiated approach principle in accordance with the nosologic category of learners with health limitations [Karabanova, 2019]. Moreover, when used in inclusive educational institutions, the individual educational path may serve as a tool for learners’ educational paths continuity [Tekhnologii razrabotki individual'nogo, 2020], which requires its institutionalization in the educational system.

To meet the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standards, general education institutions mainly use various kinds of ABEPs to address the diversity of educational needs at all educational levels, according to the research data. All types of ABEPs have been created and implemented in inclusive schools in Russia. Furthermore, all ABEP variations (from the second to the fourth), except for the first, require extension of the learning period, which makes it more difficult for learners with health limitations to integrate socially into their peer group.

The study found that separate groups in 49% of preschool educational institutions and separate classes in 18% of regular schools, separate groups in 49% of secondary vocational educational institutions, combined groups in 34% of preschool educational institutions and inclusive classes in 79% of regular schools, general groups in 51% of secondary vocational educational institutions, resource classes in 3.2% of general education institutions apply the variability of ABEP implementation techniques. It should be noted that 40% of schools use homeschooling, even though it is believed to have the least inclusive potential [Kulagina, 2015].

Creation of ILPs for learners with health limitations is necessary for all implementation strategies of inclusive education. Additionally, any learner, including those with health limitations and gifted learners, are eligible for education in line with an ILP, as required by the Education Law. In line with the FSES, the school tutor may help with teaching according to ILPs. However, ILPs are hardly ever applied in Russian educational institutions, the study reveals. Accordingly, ILPs are used to teach 0.086% of all students in vocational educational institutions, 1.34% of all regular school students, and 1.53% of all preschoolers. Therefore, the individualized approach — which requires an IEP and tutor support — is basically not used, and variability is mostly achieved based on the differentiated approach relying on the categorization of learners (by means of the ABEP). Psychological and pedagogical support and staffing issues

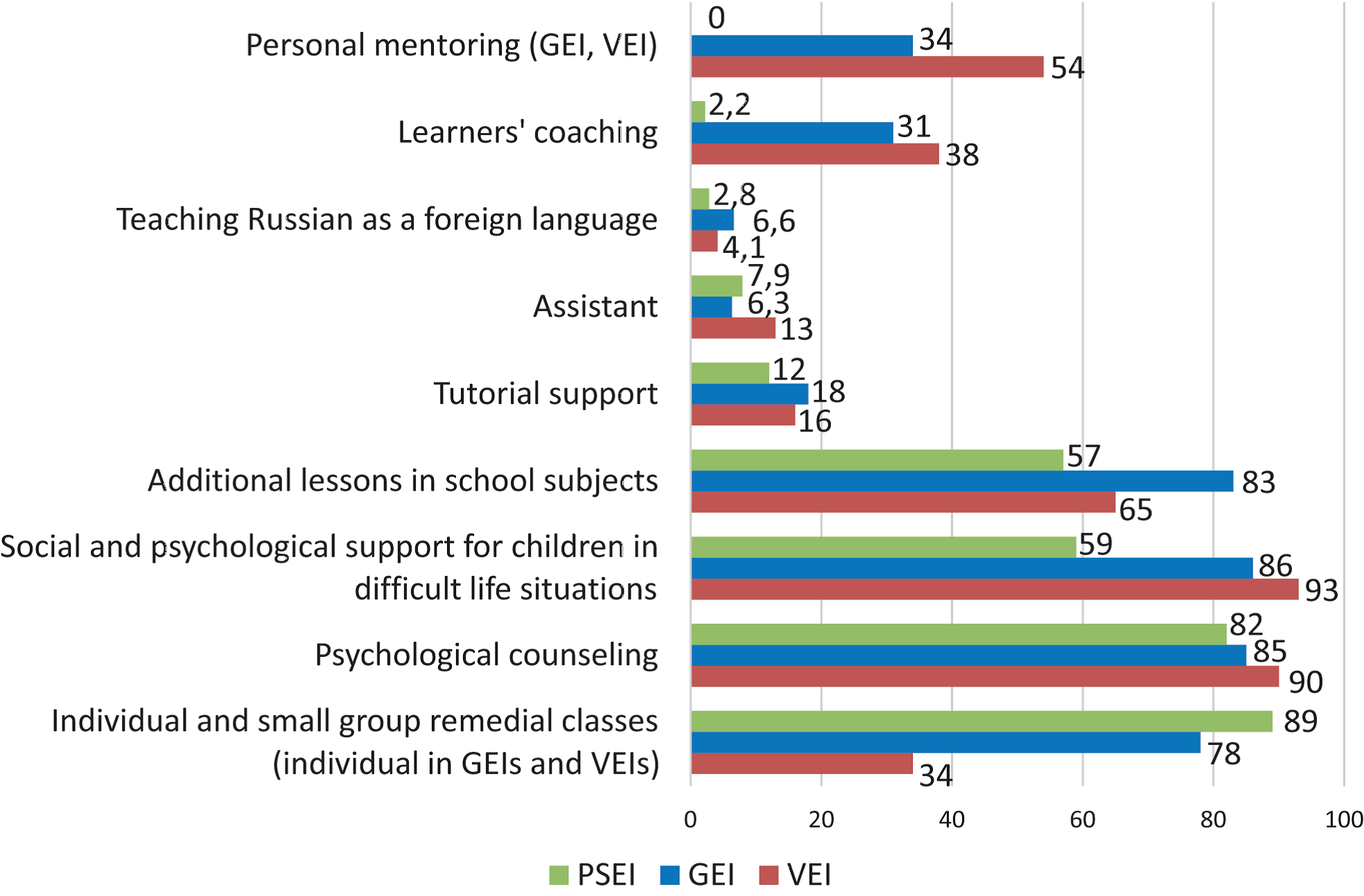

The most important condition for continuity and consistency in inclusion is the support system of the educational institution. These are the different psychological and pedagogical support techniques and technologies that serve as the foundation for both successful learning at this or that educational level and the continuation of an educational path of a learner with special educational needs as they move from one level to the next [Rubtsov, 2019]. Let us review the various forms of support offered by the educational institutions that participated in our study (Fig. 1).

Psychological counseling is the most popular type of assistance offered in educational institutions across all educational levels (82% of PSEIs, 85% of schools, and 90% of SVEIs), which indicates the development of psychological support and the accessibility of educational psychologists in educational institutions. Social and psychological support for learners with difficult living conditions is more developed in vocational schools (93%) and regular schools (86%) than in kindergartens (59%). However, compared to schools (78%) and particularly to SVEIs (34%), kindergartens (89% of PSEIs) provide individual remedial work more frequently.

Tutor assistance is one of the most important forms of support in inclusion. A tutor is an educator who offers individual guidance and continuity of a learner’s educational path [Professional'naya podgotovka t'yutorov, 2022]. However, very few educational institutions provide tutor assistance (12% of PSEIs, 18% of schools, and 16% of SVEIs). It is even more difficult to organize technical support for learners with health limitations: only 7.9% of PSEIs, 6.3% of schools, and 13% of SVEIs, provide technical assistance.

The ability of educational institutions to hire the necessary support staff is essential for ensuring continuity in assistance provision [Pis'mo Minprosveshcheniya Rossii, 2024].

The average number of students with health limitations per support specialist was determined in the study (see Tab. 2).

Even though the requirement [Prikaz Minobrnauki RF] for the availability of educational psychologists is met, more than three times as many school

Fig. 1. Percentage of EIs at different education levels that implement various support techniques

Table 2. Average number of learners with health limitations per support specialist

|

Specialist |

PSEI |

GEI |

VEI |

|

educational psychologist |

24.84 |

18.4 |

14 |

|

speech therapist |

13.2 |

29.92 |

… |

|

special educator |

57.64 |

49.88 |

295 |

|

social care teacher |

224.33 |

26.58 |

13 |

|

Tutor / learning assistant |

112.55 |

56.2 |

46 |

|

Technical assistant |

200.71 |

261.05 |

90 |

speech therapists, more than five times as many special educators, and more than nine times as many tutors are required. A tutor is employed by just 1 out of 6 SVEIs (17%), and each tutor has 46 students with health limitations assigned to them. Since special educators are only available in 3% of VEIs, SVEIs find themselves in the most challenging situation. A consistent solution is needed to ensure availability of special educators in SVEIs, given the large percentage of students with mental deficiencies in the SVEI system (Tab. 2). The issue of assessing inclusion of learners with health limitations in the educational process is brought up by the analysis of EIs’ employment of special needs education experts at all levels of education.

Ensuring involvement of teachers, parents, and learners in the education process

Learners’ educational needs support and involvement of all participants of the educational process demonstrate the educational institution’s inclusive culture. Creation of an inclusive culture serves as the basis for ensuring the inclusive process continuity in educational institutions, as well as consistency and consecutiveness of the entire educational system in inclusion implementation [But, 2007; Euscategui, 2024; Ydesen, 2024]. Involvement of teachers, parents and students in the educational process and the social life of the learners’ community is one of the most important of the many indicators used in the study to describe the inclusive culture of an educational institution.

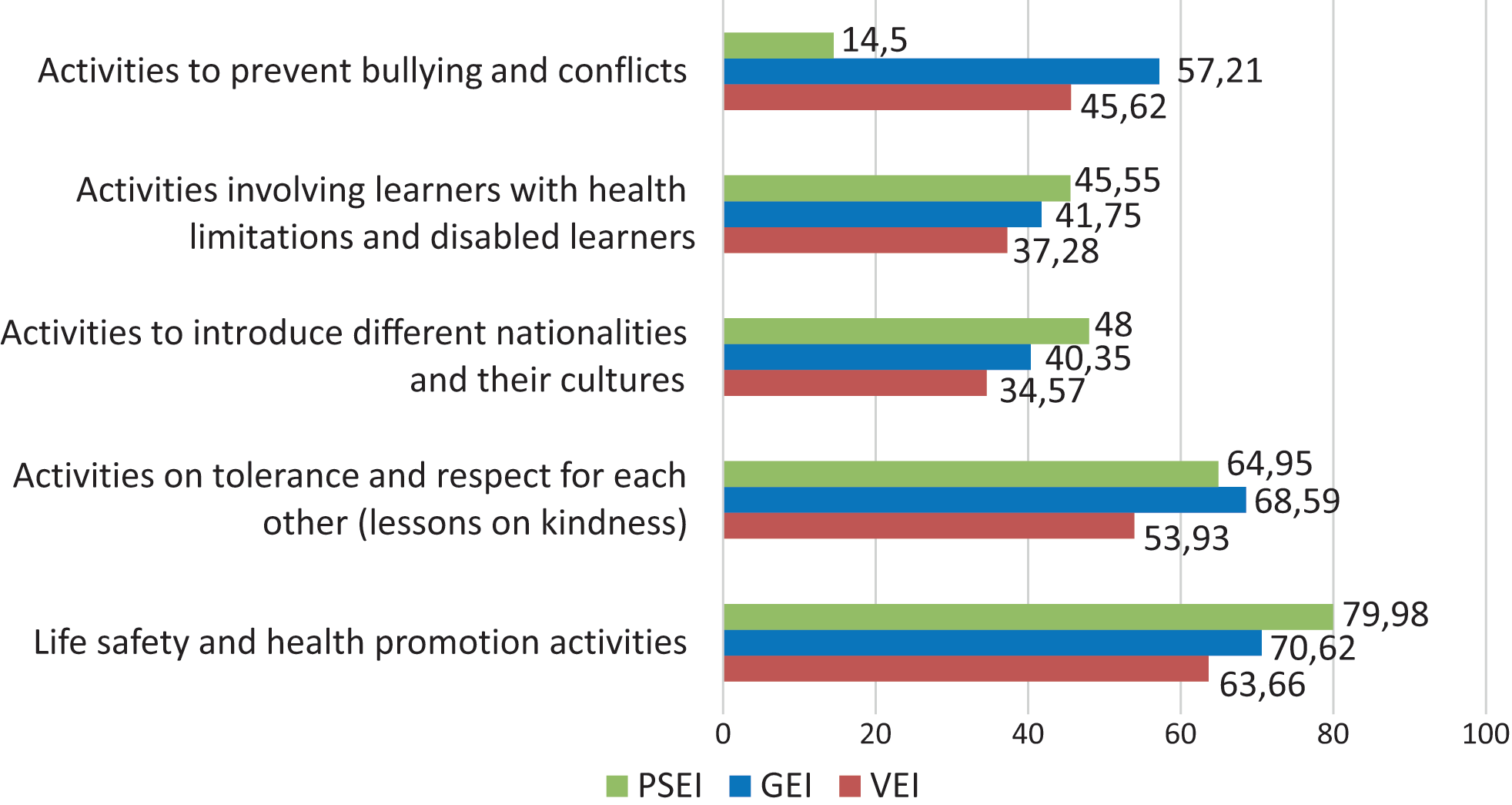

Let us review the data on teachers’ involvement in educational activities meant to create an inclusive culture (see Fig. 2).

Most teachers (80% of PSEI teachers, 70% of GEI teachers, and 64% of SVEI teachers) engage in activities that concern the health and life safety of those they teach, according to the analysis of the bar chart (Fig. 2). This highlights the importance for ensuring learners’ health and psychological safety of the inclusive environment. Most teachers (65% of PSEI teachers, 69% of GEI teachers, and 54% of SVEI teachers) participate in activities that enhance tolerance and respect for one another. Kindness lessons have gained popularity in educational institutions and are now an integral part of Russian educational programs.

Bullying and a strong propensity for conflict are fairly common issues in educational institutions. Taking part in activities that encourage tolerance and respect for the diversity of SEN is one of the ways to prevent them [Bochaver, 2013; Bystrova, 2022a; Volkova, 2021]. Approximately 46% of SVEI teachers and 57% of schoolteachers participate in activities dedicated to this topic. The fact that just 14% of preschool teachers participate in activities addressing bullying and conflicts, however, indicates that these issues are no objects of interest for teachers in PSEIs.

At schools and at SVEIs, the proportion of teachers who organize activities for students with disabilities and health limitations (46% at PSEIs, 41% at GEIs, and 37% at SVEIs) and participate in activities that expose students to different cultures (48% at PSEIs, 40% at GEIs, and 34% at SVEIs) is slightly smaller than that in nursery schools. On the contrary, the proportion of learners whose

Fig. 2. EIs teachers’ involvement in activities, (%): PSEIs — 20,997 teachers,

GEIs — 23,578 teachers, VEIs — 16,295 teachers

mother tongue differs from that of teaching doubles as they progress from preschool to school (Tab. 1). It is shown that exposure to different cultures and a greater understanding of difficulties faced by learners who have emotional and behavioral disorders, learning challenges, and other issues can promote better understanding and enhance the school climate [Dobson, 2024; Lenkeit, 2024].

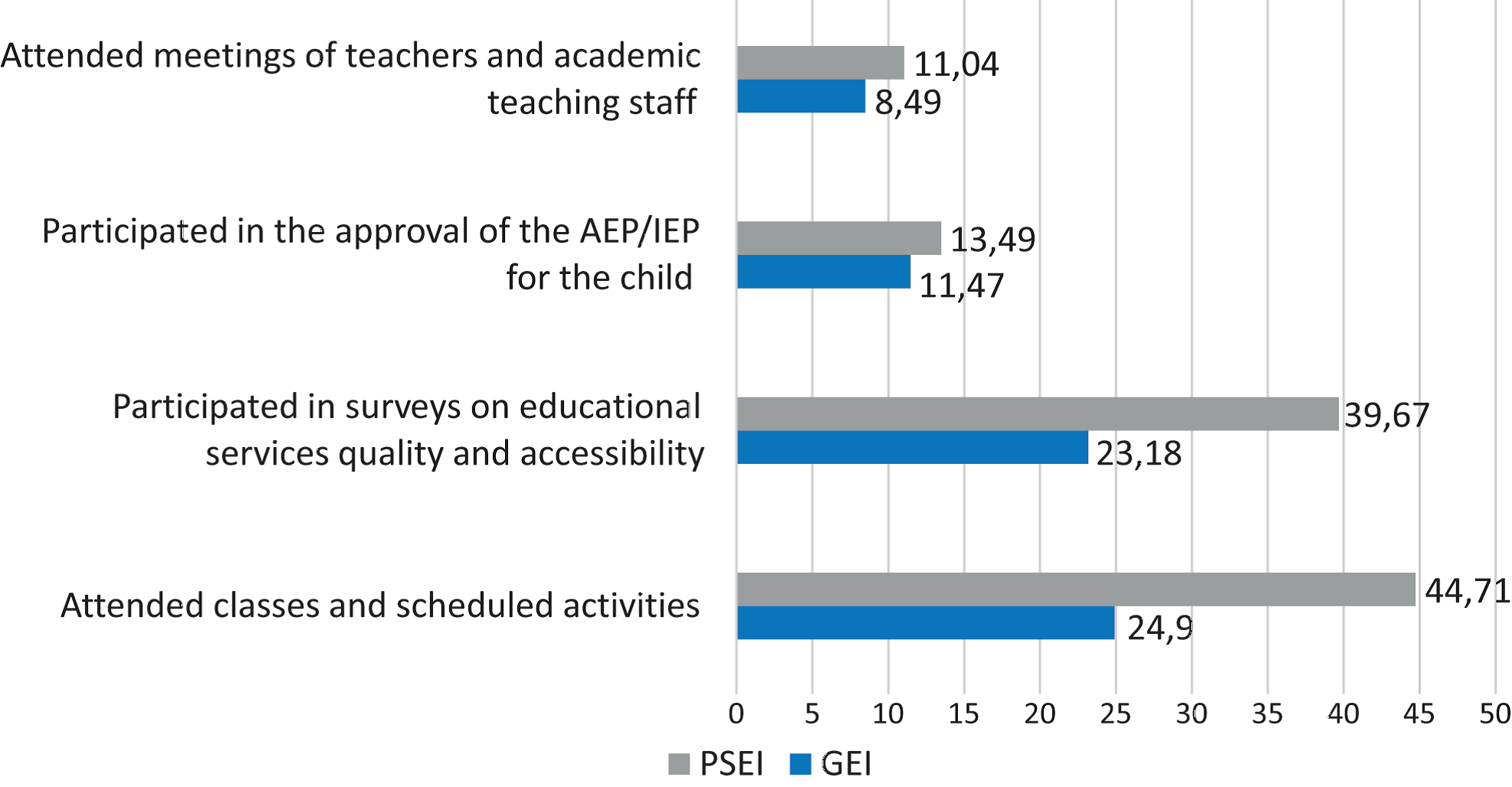

Knowing that parental involvement directly affects the quality of the IEE [Alekhina, 2023; Afon'kina, 2020; Indenbaum, 2021], the study examined the level of parental engagement in educational institutions’ operation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Percentage of parents involved in educational institutions’ activities (%): PSEIs — 44,033 people, including 26.06% of parents of learners with health limitations; GEIs — 48,060 people, including 35.87% of parents of learners with health limitations

According to the analysis’s findings (Fig. 3), parents’ involvement in PSEIs is twice as high as that of in schools in terms of attending classes and participating in planned activities (walks, midday sleep, etc.) and taking part in surveys on the accessibility and quality of educational services. According to 11% of parents at schools and 13% of parents at PSEIs, they participate in the approval of their children’s IEPs and ABEP. 11% of parents at PSEIs and 8% of parents at schools report their participation in the meetings with psychological and pedagogical experts, which is well correlated with the proportion of children learning according to ABEP and IEP at the general education level. The data confirms that, for the most part, the legal requirement [Federal'nyi zakon Rossiiskoi] to have parental consent for these documents is met.

PSEI and GEI learners’ involvement was evaluated based on the assessments by their parents, whereas SVEI level students were asked to reply to questions themselves. It is important that almost at every educational level, learners are more engaged in activities that are organized by adults rather than on their own initiative. These activities include celebrations and sports events (87% of preschoolers, 63% of schoolchildren and 28% of vocational education students), trips and excursions (32%, 57% and 19% respectively), hobby clubs and workshops (68%, 64% and 22% respectively), academic competitions and contests (59%, 54% and 6% respectively). However, in situations when initiative and personal attitude are required, such as IEPs development (10.5% of schoolchildren and 3.6% of vocational education students), volunteer work (28% and 18% respectively), coaching and/or mentoring other students (9.7% of schoolchildren), and project work (38% and 8% respectively), low levels of learners’ participation are observed. Another important point is that when students approach the level of secondary vocational education, their social involvement drastically declines.

This data does not reduce opportunities for students to participate in social activities, which fosters development of their social skills and the sense of community. Learners’ good qualities and support of their teachers have the strongest influence on creating a sense of belonging [Allen, 2018].

Personal involvement and interest are key for learners’ development [Alekhina, 2022]. A clear desire to participate helps to enhance interest in learning and involvement in both social and academic life. [Fomina, 2022]. A learning environment that takes into account each learner’s unique requirements and interests needs to be established to support learners in developing this experience. The basis for learners’ successful continuous education is their readiness and willingness to study [Lubovskii, 2016]. Thus, it opens a promising perspective for further psychological studies in inclusive education.

Support in professional identity and selection of a professional education path

Various programs of career guidance counseling are one of the ways to ensure education continuity across all levels of education. The main goal of these programs is to inform learners about available professions, working conditions, and learning opportunities in their field of interest, which, in its turn, allows learners to make informed decisions on their professional education paths [Kantor, 2018].

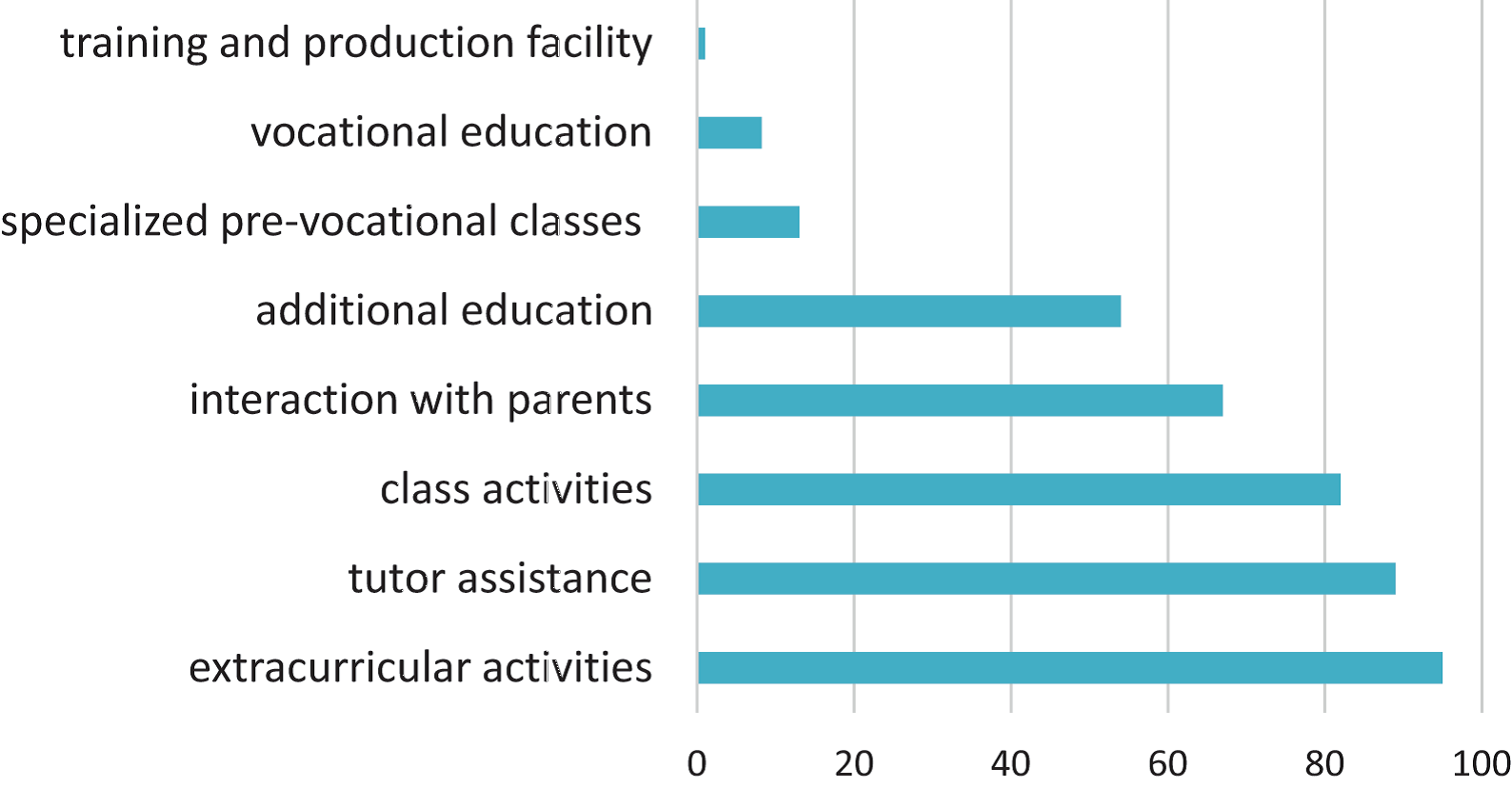

According to the study, schools offer a variety of career guidance counselling services to students with health limitations (Fig. 4).

Yet, pre-vocational training, which is so efficient for learners with health limitations and helps them to improve their social and practical skills, is only used in 8.2% of schools. The percentage of schools offering specialized pre-vocational training makes up just 13%. The percentage of learners with health limitations who completed pre-vocational training in 2023 amounts to just 5.85% (about 1 of 17 learners with health limitations), as only 1% of Russian schools use training and production facilities (Fig. 4). This is partially due to the schools’ insufficient material and technical base and the underdeveloped system of networking with specialized organizations,

Fig. 4. Percentage of GEIs offering different types of career counseling and support to students with health limitations

including non-profit organizations that could provide this resource. The practical use of vocational guidance technologies as a means of education continuity may be hampered by the lack of such interaction mechanisms in schools.

It should be noted that 62.56% of learners with health limitations enrolled in SVEIs without prior career counseling in school. It demonstrates a possible efficiency of other career counseling strategies for learners with health limitations, i.e. additional education (54%), extracurricular activities (95%) and tutor assistance (89%). Studies suggest that socially oriented career guidance activities (dramatization games, excursion tours, practical training, group counseling, professional situations simulations, etc.) organized for both learners with health limitations and their ordinary peers [Bystrova, 2022; Kantor, 2018; Kovalenko, 2021] help develop social competences for all learners (including those with health limitations), initiate a group interaction in a diverse environment, broaden the scope of social experience and skills transfer to new activities. All of this is essential for the professional identity and transition to a new level of education with a further integration into a profession.

Conclusion

According to the data analysis in this article, the overall pool of some categories of learners with health limitations (mental development delay, ID, visually impaired, and hearing impaired) remains constant throughout their schooling, whereas most of other categories of learners with health limitations (blind, deaf, and ASD) leave inclusive schools at the basic general education level and appear to transfer to specialized educational institutions.

Let us focus on the key findings for the four fundamental measures of inclusive process continuity:

- Ensuring diversity in plans, programs, and teaching methods. All types of ABEP have been developed and implemented by inclusive educational institutions in Russia at all educational levels, including resource classes, separate classes (groups), and joined education. However, only 1.34% of learners in inclusive schools are taught according to ILPs, which suggests that the individual approach’s resources are not being used to their full potential. Besides, learners with health limitations and disabilities continue to face challenges of homeschooling, which hinders their social inclusion. Both issues require their own technological solution. Russian education must institutionalize the individual educational path as the primary means of implementing continuity.

- Psychological and pedagogical support for learners with special educational needsand its staffing. For learners with special educational needs, a variety of pedagogical and psychological support tools serve as the basis for their educational path continuity. Psychological support for learners is the most common type of assistance in EIs at all educational levels. Lack of remedial support resulting from a shortage of special educators, particularly at the SVE level, is the primary shortfall of assistance service in inclusive EIs. Only every tenth educational institution has a tutor working as a teacher who directly maintains the learner’s IEP’s consistency and continuity, allowing the learner to establish and maintain their subjective attitude.

- Ensuring participation of all learners and their parents in the education process and the educational institution’s activities. Teachers’, parents’ and learners’ engagement in the education process and social life is a key indicator of inclusive culture. This culture develops gradually and is influenced by the actions of those involved in educational processes. The engagement indicator’s multidimensional character requires psychological and pedagogical examination as well as additional multifaceted research.

- Support in professional identity and selection of a professional education path. Vocational guidance for learners is frequently viewed as a method that helps them develop social competencies required for their integration into work environments. Yet, schools underutilize such useful resources as attending training and production facilities or specialized pre-professional classes, which can decrease the quality of career guidance and subsequent inclusion during the transition from school to the secondary vocational education level.

The study of the above identified indicators in their dynamics determines the perspectives for future research, allowing for tracking of changes in education personalization, staffing of psychological and pedagogical support for learners to ensure inclusion, and development of successful vocational guidance techniques. It is also important to study different factors of social engagement that include psychological and pedagogical as well as socio-psychological aspects of creating learners’ sense of belonging to the local community and that of the educational institution because it can lay the foundation for future active social inclusion of educational institutions’ graduates and help them forge their own unique life paths.