Introduction

The current trend in organizing the process of obtaining full secondary education in Russia is toward diversifying available educational environments for adolescents aged 15–17. In recent years, there has been intensive development within the system of secondary professional education aimed at early entry into professions for older adolescents: the number of specialized secondary institutions has increased; their variety has expanded; and new forms of educational processes are being introduced.

Since 2023, a federal project called “Professionalitet” has been implemented within this system. Under this project, college students can both study and work directly in their chosen specialty. The impact of this combination on learning motivation has been widely discussed both domestically and internationally. During these discussions, various opinions have been expressed—including opposing views (Egorenko, 2019; Nimets & Tolstykh, 2024).

The educational context for senior grades in secondary schools is undergoing transformation—particularly due to ongoing controversies surrounding the unified state exam—their content, formats, preparation methods—and so forth.

Today’s diverse secondary schools and colleges represent different educational environments with varying objectives; however, their common goal remains providing adolescents with opportunities to obtain secondary education and organize meaningful learning activities.

It is generally recognized that learning motivation constitutes a crucial component of educational activity. Optimizing learning motivation across different environments presents a complex practical challenge that requires an understanding not only of personal development processes during late adolescence (early youth) but also knowledge about specific features unique to each educational setting.

The research problem lies in clarifying these specific features within the modern Russian secondary education context. Accordingly, this study aims to identify particular aspects of educational motivation related to personal development among older adolescents studying across various types of institutions. The main tasks are: first, selecting relevant educational environments for comparison; second, determining appropriate methodological tools and statistical methods for analyzing empirical data.

Materials and methods

This article presents the results of a comprehensive study of learning motivation in the context of general process of personal development of adolescents studying in three different educational environments: senior grades of secondary school, prestigious college training architects and designers (college 1) and much less prestigious college training cooks and automotive technicians (college 2). All these educational institutions are located in Moscow and Moscow region. The age of the study participants is 16-18 years old (10-11 school grades and 1-2 college courses). The sample characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Sex |

School |

College 1 |

College 2 |

Total |

|

Boys |

87 |

28 |

25 |

140 |

|

Girls |

88 |

99 |

15 |

202 |

|

Total |

175 |

127 |

40 |

342 |

The study was carried out during in 2021-2022.

The general study hypothesis supposed the existence of significant differences in the nature of the learning motivation of students of three educational environments indicated above and in the place of this motivation in general structure of motivation-need sphere of students’ personality and in a number of other personal characteristics of these adolescents.

The following research methods were used for empirical verification of the particular hypotheses arising from the general one:

-

Method of Motivational Induction (MMI) by J. Nuttin (Nuttin, 2004; Tolstykh, 2005; Nuttin, 1980).

-

"Academic Motivation Scale for Schoolchildren" (AMS-S) created by T.O. Gordeeva et al. (Gordeeva et al., 2017).

-

"Satisfaction with Life Scale" (SWLS) by E. Diener adapted by E N. Osin and D. A. Leontiev (Osin, Leont'ev, 2020).

-

"Achievement Goal Questionnaire" (AGQ) – the Russian version of the questionnaire by E. Elliott et al. (Nikitskaya, Uglanova) (Nikitskaya, Uglanova, 2021).

The MMI research method allows us to consider the entire range of motivation in older adolescents. Completing unfinished sentences formulated in the first person encourages respondents to spontaneously list motivational objects that are desirable or, conversely, undesirable for them across various spheres (Nuttin, 2004; Tolstykh, 2005; Nuttin, 1980).

The AMS-S research method distinguishes scales of intrinsic motivation (cognitive motivation, achievement motivation, and self-development motivation), extrinsic motivation (motives of self-respect and introjected regulation), external regulation (positive—such as respect from parents—and negative), and amotivation (Gordeeva et al., 2017).

The authors of the Russian version of the SWLS research method state that it reflects the evaluative and reflexive components of subjective well-being. It describes the respondent’s attitude toward life: an assessment of life circumstances as positive, a desire to change the past or their way of living, and so on (Osin & Leont'ev, 2020).

The AGQ research method analyzes learning goals related to (1) achievement of learning tasks, (2) self-development, and (3) demonstration of knowledge and skills in comparison to others. These are the goals that students seek to achieve or avoid (Nikitskaya & Uglanova, 2021).

Results

The place of learning motivation in the general structure of the motivation sphere of older adolescents

At the beginning of the analysis, let us consider the place of learning motives within the general structure of the motivation sphere of older adolescents studying in different educational environments.

On one hand, the problem is interesting because the question of the leading activity of adolescence remains open. As a rule, discussions about it are of a general-theoretical nature. On the other hand, empirically, learning motivation is usually studied separately, and all research methods are aimed at that. We used the projective method of motivational induction (J. Nuttin), which allows us to identify the “weight” of learning motivation within the context of those substantive components to which the author categorizes all “motivational objects.” According to Nuttin, "...the high frequency of indicating a certain motivation in the MMI is an indicator of the intensity of this motivation" (Nuttin, 2004, p. 545).

Based on the replies of the respondents the original list of substantive categories named by J. Nuttin was reduced in our study: those categories of responses that is difficult to attribute to a specific category as well as replies containing transcendental component that appeared very rare in our study were eliminated; the category of responses reflecting the will to have money (not to possess something, but “to earn much”, “to have plenty of money”, “to be wealthy”) was added. Thus, the following 9 motive categories remained for further consideration:

R3 – learning motives;

R – realization motives related to any other activity;

S – self motives related to one’s own personality;

SR – self-realization motives;

C – communicative motives;

E – exploration motives;

P – possession motives related to the desire of possessing of material assets;

L – leisure motives related to recreation;

$ – motives related to money.

In this study the adolescents were to complete 10 unfinished sentences: 7 of them started from positive “inductors” (“I want…”, “I plan…” and so on) and the other 3 started from negative ones (“I don’t want…” and so on).

The distribution of adolescents’ expressions completing the sentences-inductors, in % from the total amount of expressions in each group of respondents, can be found in Table 2.

Table 2 . Place of learning motives (R3) in motivational structure of adolescents studying in different educational environments

|

Школа / School |

Колледж 1 / College 1 |

Колледж 2 / College 2 |

|||

|

Category from MMI |

Rating (%) |

Category from MMI |

Rating (%) |

Category from MMI |

Rating (%) |

|

S |

34,4 |

S |

32,1 |

S |

37,4 |

|

R3 |

18,4 |

R |

16,9 |

R |

15,4 |

|

R |

16,1 |

С |

15,8 |

С |

14,2 |

|

С |

12,9 |

R3 |

11,7 |

P |

9,5 |

|

L |

6,3 |

L |

10,5 |

L |

9,1 |

|

$ |

4,4 |

$ |

5,2 |

R3 |

7,4 |

|

SR |

3,7 |

SR |

3,3 |

$ |

3,1 |

|

P |

2,3 |

P |

2,6 |

SR |

2,7 |

|

E |

1,5 |

E |

1,9 |

E |

1,2 |

As can be seen in Table 2, learning motives (R3) occupy different positions within the motivational sphere of adolescents studying in various educational environments. Learning is the most significant motive for school students (second place in the overall structure). It ranks fourth among college 1 students and sixth among college 2 students. According to J. Nuttin's coding rules for expression content, this category includes adolescents’ responses related both to learning in general (“want to graduate from school well,” “want to enter university,” “want to study well”) and specific learning situations (“want to finish my project this week,” “want to improve my score in Russian,” “don’t want to go to chemistry class”).

It is noteworthy that self-motives related to one’s own personality (S) rank first in the motivation structure of adolescents across all three educational environments. Expressions such as “I want all my dreams to come true,” “I want to be successful,” “I want to achieve all my goals,” and others fall into this category.

Another common feature among the three respondent groups is the placement of exploration motives. This category includes expressions related to a desire to explore or learn about something. For example: “I would like to know how comics are created,” “I want to know the traditions of other nations,” “I would like to know more about my future profession,” and others.

When testing the assumption that there are significant differences in the position of learning motivation within the overall motivation structure among older adolescents in different educational environments, a Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted (H = 12,841; df = 2; p = 0,002). Pairwise post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed statistically significant differences between the group of schoolchildren and college 2 students (p < 0,01): learning motivation is higher among schoolchildren.

In addition to analyzing the position of learning motives within the motivational sphere, we examined their relationship with other motives among older adolescents (based on MMI results) across different educational environments. The results of this correlation analysis (Spearman rank correlation coefficient) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Correlation between learning motives (R3) and other motives (MMI) in three groups of older adolescence

|

Category from MMI |

School (R3) |

College 1 (R3) |

College 2 (R3) |

|||

|

ρxy |

α |

ρxy |

α |

ρxy |

α |

|

|

S |

-0,319** |

0,000 |

-0,356** |

0,000 |

-0,185 |

0,345 |

|

R |

0,065 |

0,430 |

0,170 |

0,076 |

0,390* |

0,040 |

|

C |

-0,394** |

0,000 |

-0,292** |

0,002 |

-0,289 |

0,136 |

|

L |

0,018 |

0,828 |

0,164 |

0,089 |

-0,019 |

0,924 |

|

$ |

-0,072 |

0,381 |

-0,123 |

0,202 |

0,129 |

0,513 |

|

P |

-0,018 |

0,826 |

-0,175 |

0,068 |

-0,281 |

0,148 |

|

SR |

-0,143 |

0,081 |

-0,030 |

0,757 |

0,424* |

0,025 |

|

E |

-0,006 |

0,944 |

0,080 |

0,409 |

-0,200 |

0,309 |

Note: «**» — significance level p≤0,01; «*» — significance level p≤0,05.

Learning motives in school and in both colleges revealed inverse relation to motives related to one’s own personality (S) and communication motives (C). College 2 results revealed direct relation of learning motives to motives related to any other activities (R) and self-development motives (SR).

Characteristics of learning motivation of older adolescents studying in different educational environments

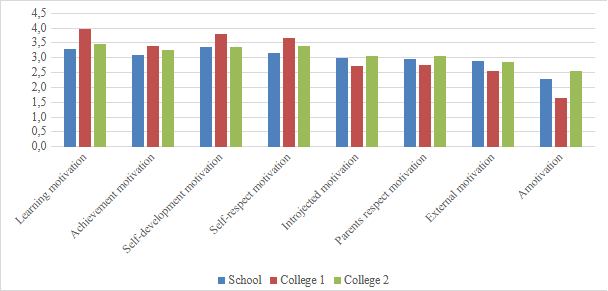

Having considered the position of learning motives within the general motivation structure of older adolescents studying in different educational environments, we proceed to analyze learning motivation in each group using the AMS-S research method. The scores on each AMS-S scale for the three groups of older adolescents are presented below (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of learning motivation differ among different groups of older adolescents: when applying the Kruskal-Wallis test, significant differences were found on six out of nine scales (Table 4).

Table 4. Difference between learning motivation (AMS-S) in three groups of older adolescents

|

|

Cognitive motivation |

Achievement motivation |

Self-development motivation |

Self-respect motivation |

Introjected motivation |

Parents respect motivation |

External motivation |

Amotivation |

|

H Крускала-Уоллеса / Kruskal- Wallis |

26,995 |

4,772 |

11,186 |

16,191 |

7,518 |

3,868 |

6,428 |

30,483 |

|

df |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

p |

0,000** |

0,092 |

0,004** |

0,000** |

0,023* |

0,145 |

0,040* |

0,000** |

Note: «**» — significance level p≤0,01; «*» — significance level p≤0,05.

Subsequent pairwise post-hoc comparisons between the three groups of students (with the Bonferroni correction for several tests) revealed significant differences on five out of nine scales of the AMS-S research method.

Cognitive motivation and self-respect motivation differ significantly between groups of schoolchildren and students of both colleges (for schoolchildren, indicators on both scales are significantly lower: p ≤ 0,01, p ≤ 0,05). There are no significant differences between the students of the two colleges on these scales.

Significant differences between the groups of schoolchildren and college 1 students are obtained on the scales of "Self-development motivation" (the indicators are higher for college 1 students: p ≤ 0.01) and "External motivation" (higher for schoolchildren: p ≤ 0,05).

College 1 students had the lowest scores on the "Amotivation" scale: they are significantly lower than in the group of college 2 students (p < 0,01) and in the group of schoolchildren (p < 0,01). There are no differences on this scale between the groups of college 2 students and schoolchildren.

The data obtained during the processing of the AMS-S research method, which are the basis for the presented results, is available in the repository of psychological research and tools of MGPPU (Nikitskaya, 2024).

Learning motivation and the rate of life satisfaction of older adolescents studying in different educational environments

Nowadays the scholars note that the base of successful personality development is laid during the education period (Bondarenko, Fomina, 2023). Educational programs are aimed both at competence development of students and at the maintaining an optimal level of their psychological well-being. The relation of life satisfaction, which is an integral indicator of personality development, based on the subjective student’s perception of the balance of positive and negative affects, to individual characteristics, learning motivation and educational environment is studied by many scientists (Golovei, Danilova, Gruzdeva, 2019; García-Ros, R., Pérez-González, F., Tomás, J.M. et al., 2023; Kaya, 2021; Klapp, Klapp, Gustafsson, 2924; Morosanova, Fomina, Bondarenko, 2021).

To form a more complete understanding of some of the personality traits of older adolescents studying in different educational environments, a correlation analysis (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient) was conducted between indicators of life satisfaction (SWLS) and various components of learning motivation (MMI, AMS-S, AGQ) of older adolescents.

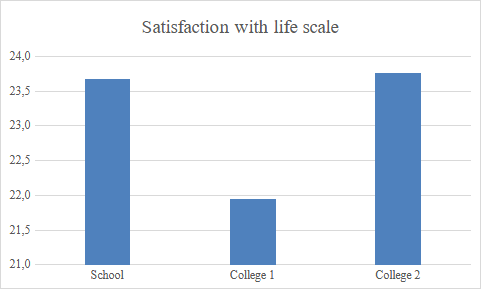

Preliminarily a comparative analysis of the life satisfaction rate was carried out in three groups of participants (Fig. 2).

The empirical data obtained so far allow us to consider a life satisfaction score of 16 points as low, and scores of 25 points and above as high (Osin & Leont'ev, 2020). As can be seen in Figure 2, all three groups of older adolescents have a medium level of life satisfaction; however, the life satisfaction rates for school students and college 2 students are higher compared to those for college 1 students. The statistics do not reveal this difference when comparing the two colleges due to the relatively small sample size from college 2.

Correlation analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient revealed the relationship between life satisfaction scores and learning motivation among older adolescents studying in each of the three educational institutions (Table 5).

In addition to examining the relationship between learning motivation and various aspects, we also considered the relationship between life satisfaction and learning achievement goals (AGQ).

The AGQ assessment method consists of six scales:

1 – self-achievement goals (to do better than I did before);

2 – self-avoidance goals (not to do worse than I did before);

3 – task-achievement goals (to cope with a task well);

4 – task-avoidance goals (not making mistakes when solving a task);

5 – performance-achievement goals (to do better than others);

6 – performance-avoidance goals (to do no worse than others).

Table 5. Correlations between life satisfaction rate (SWLS) and learning motives (R3 from MMI), educational achievement goals (AGQ), learning motivation (AMS-S) in three groups of older adolescents

|

Rate of various parameters from MMI, AGQ, AMS-S |

School (SWLS) |

College 1 (SWLS) |

College 2 (SWLS) |

|||

|

ρxy |

α |

ρxy |

α |

ρxy |

α |

|

|

R3 (MMI) |

-0,053 |

0,520 |

0,214* |

0,025 |

0,455* |

0,015 |

|

Self-approach goals (AGQ) |

0,259** |

0,001 |

0,193* |

0,044 |

0,296 |

0,126 |

|

Self-avoidance goals (AGQ) |

0,272** |

0,001 |

0,118 |

0,221 |

0,244 |

0,210 |

|

Task-approach goals (AGQ) |

0,357** |

0,000 |

0,239* |

0,012 |

0,283 |

0,144 |

|

Tak-avoidance goals (AGQ) |

0,248** |

0,002 |

0,165 |

0,086 |

0,107 |

0,587 |

|

Other-approach goals (AGQ) |

0,191* |

0,019 |

0,060 |

0,538 |

0,263 |

0,176 |

|

Other-avoidance goals (AGQ) |

0,173* |

0,034 |

0,170 |

0,078 |

0,215 |

0,272 |

|

Cognitive motivation (AMS-S) |

0,467** |

0,000 |

0,296** |

0,002 |

0,425* |

0,024 |

|

Achievement motivation (AMS-S) |

0,415** |

0,000 |

0,163 |

0,090 |

0,464* |

0,013 |

|

Self-development motivation (AMS-S) |

0,437** |

0,000 |

0,209* |

0,029 |

0,326 |

0,091 |

|

Self-respect motivation (AMS-S) |

0,230** |

0,004 |

0,129 |

0,181 |

0,265 |

0,173 |

|

Introjected motivation (AMS-S) |

0,042 |

0,613 |

0,150 |

0,120 |

0,164 |

0,406 |

|

Parents respect motivation (AMS-S) |

-0,049 |

0,550 |

0,005 |

0,961 |

0,261 |

0,180 |

|

External motivation (AMS-S) |

-0,318** |

0,000 |

-0,117 |

0,225 |

-0,160 |

0,417 |

|

Amotivation (AMS-S) |

-0,278** |

0,001 |

-0,243* |

0,011 |

-0,345 |

0,072 |

Note: «**» — significance level p≤0,01; «*» — significance level p≤0,05.

In the group of schoolchildren, a high level of direct relation to life satisfaction is confirmed for all academic achievement goals (AGQ) and intrinsic motivation (AMS-S) (p ≤ 0,01; p ≤ 0,05). An inverse relation is observed between the life satisfaction score and external motivation as well as amotivation (p ≤ 0,01).

Results for college 1 students demonstrate a statistically significant direct relationship between learning motives (MMI) (p ≤ 0,01), self-achievement, and task-achievement goals (AGQ) (p ≤ 0,05). An inverse relationship with amotivation (AMS-S) is also identified at p ≤ 0,05.

For older adolescents studying at college 2, a direct relationship exists between life satisfaction and both learning motives (MMI) and intrinsic motivation (AMS-S) at p ≤ 0,05; additionally, an inverse trend with amotivation was observed at p ≤ 0,072.

By calculating correlation coefficients for each educational environment listed in Table 5, we used Fisher’s z-transformation to compare these coefficients pairwise.

Significant differences in correlations between life satisfaction and learning motives—specifically R3 according to MMI—were found between groups of schoolchildren and college 1 students at p < 0.05, as well as between groups of schoolchildren and college 2 students at p < 0,01. In both colleges, this relationship was positive but significantly different from that observed in the group of schoolchildren.

The correlation between cognitive motivation (AMS-S) and life satisfaction was significantly higher among schoolchildren than among college 1 students at p < 0,05; no significant difference was found with respect to college 2 students.

Furthermore, the relationship between achievement motivation and life satisfaction was lower among college 1 students compared to both schoolchildren (p < 0,01) and college 2 students (p < 0,05); no difference was observed between college 2 students and schoolchildren.

Finally, the association between self-development motivation—measured by AMS-S—and life satisfaction was higher among schoolchildren than among college 1 students (p < 0,05).

Thus, we observe that life satisfaction among adolescents studying in three different educational environments relates differently to various components of learning motivation.

Discussion

In our opinion, the selected groups of adolescents can serve as key reference points reflecting the diversification of the process of completing secondary education at this stage.

It is natural to suppose that the learning motivation of students in these educational institutions—being an equally important component of their learning activity—differs in content and level across them. The study confirmed this by identifying specific characteristics of older adolescents’ learning motivation in three different educational environments.

First, a comparative analysis showed that learning motives occupy different positions within the overall structure of adolescents’ motivation-need sphere and differ in their “weight” and significance. This conclusion was drawn based on using J. Nuttin’s projective research method—motivational induction (MMI). By completing inductor sentences ("I want...", "I dream...", "I do not plan...", etc.), respondents can write extensively, briefly, or not at all about certain “motivational objects” (a term introduced by J. Nuttin). It is believed that the more frequently a respondent writes about certain motives, the more important those motives are for him. Based on this logic, it was found that learning motives are most important for school students and least important for students at college 2.

However, it was also revealed that learning motives do not occupy the first position in any of the adolescent groups. Instead, this position—by a wide margin—is occupied by motives related to one's own personality across all three groups. Following the logic of A.N. Leontiev, we may say that the dominance of such motives among older adolescents reflects the paramount importance they assign to self-determination, self-exploration, and identity formation. This general age-related characteristic of the motivational hierarchy—independent of specific educational environments—can serve as an argument in ongoing discussions about leading activities during older adolescence (early youth). It should be noted that educational-professional activity is widely accepted today as a leading activity for older adolescents; therefore, it would be logical to expect a dominance or combination of learning motives with motives that Nuttin classifies as work-related. This assumption has been refuted.

An important—though unfortunately expected—fact obtained through MMI is a clear discrepancy between learning motives and exploration motives, which in all three groups ranked last in terms of frequency of mention. Exploration motives are least expressed among college 2 students and most among college 1 students; school students show medium levels. This fact can also be considered expected because college 1 students are young people who have already chosen their future specialty and are striving for results—including creative achievements—that aim at self-fulfillment within their chosen profession.

Although college 1 students demonstrated, as expected, the most “productive” learning motivation (they exhibit higher intrinsic motivation and lower amotivation according to AMS-S data), our study shows that for this group of older adolescents it is not learning per se that matters most but rather self-development and a focus on professional growth as an ability to cope with tasks—evidenced by high significance levels in relationships between self-achievement goals and task-achievement goals based on AGQ, along with life satisfaction rates.

For school students, on the contrary, general learning appears to be more important. This conclusion is based firstly on their ranking second in learning motives within their motivational structure according to MMI results (R3), secondly on evidence from AMS-S showing a direct relationship between life satisfaction and intrinsic motivation as well as self-respect motivation—and an inverse relationship with external motivation and amotivation—and thirdly on findings from AGQ indicating a relationship between life satisfaction and all types of learning achievement goals. Presumably, the high importance placed on learning activity during senior grades stems from preparation for imminent university admission.

For college 2 students, however, learning as an activity does not seem to significantly influence their subjective sense of life satisfaction. It is no coincidence that their learning motives have the lowest “weight” within their motivational structure according to MMI compared to other groups; additionally, none of their learning achievement goals (AGQ) are related to life satisfaction (SWLS).

Having described the specifics of learning motivation of older adolescents from different educational environments, we consider it important to note another characteristic common to all groups of adolescents. The direct relation of life satisfaction to various scales favorable for learning motivation according to AMS-S and the inverse relation to amotivation in all three groups of students allows us to state the importance of learning activity in assessing the ratio of positive and negative affects in life by an older adolescent (which is revealed by the SWLS research method), regardless of the learning motives place in the motivation-need sphere and regardless of the specific characteristics of learning motivation. This fact confirms the results of previous studies conducted in Russia and abroad on the relation of the subjective perception of positive and negative affects in a student's life to learning motivation (Bondarenko, Fomina, 2023; Egorenko, 2019).

This conclusion is also correlates with the fact that, with medium rates of life satisfaction in all three groups of older adolescents, the lowest rates are demonstrated by college 1 students (with the most "productive" learning motivation).

Apparently, college 1 students are characterized by a will to understand themselves, an increased level of anxiety, and a large number of fears. We make this conclusion not only based on the results of statistics, but also on the basis of an analysis of the content of the questionnaires. The forms filled out by students of this group of adolescents differ sharply from the other ones in both the nature of what is written and the volume of the responses.

Conclusions

- The study reveals the following characteristics of the motivation-need sphere, common to all three groups of adolescents surveyed (senior grades school students and their peers from two diametrically different colleges in terms of prestige, with different levels of entrance tests and academic performance requirements for applicants):

- 1.1 The first place in importance is taken by motives related to one's own personality, which allows us to consider the activity of self-determination, the search for one's identity as leading in older adolescence.

- 1.2 Exploration motives take the last place in all three groups of adolescents, thus being the least subjectively significant, and, as it turned out, unrelated to learning motives.

- The learning motivation of 16-18-year-olds studying in different educational environments varies both in place among other motives and in its specific characteristics.

- The rates of life satisfaction are differently related to different aspects of learning motivation in the three surveyed groups, which confirm the above statements about the fundamental difference in the role of learning motivation both in the context of the activities of adolescents studying in different educational environments and in the context of their personality development. In our opinion, it is precisely the peculiarities of personality development that can explain the significantly lower rates of life satisfaction among students at a prestigious college.

Limitations. This study is limited by the disproportion among the three surveyed adolescent groups and by gender imbalance within these groups.