Introduction

It is well-established that the quality of school students' motivation determines their level of academic achievement (Gordeeva et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2021), and motivation itself is largely dependent on the teachers’ relationship with students and teachers’ interaction style (Aelterman et al., 2019; Bureau et al., 2022). Research on effective strategies to support student motivation is particularly relevant in recent years, given its decline among modern school students.

This study is based on a model grounded in Self-Determination Theory, which includes four main interaction styles: two motivating styles—autonomy-supportive and structuring—and two demotivating styles—controlling and chaotic, each of which is further subdivided into two subtypes (Aelterman et al., 2019). This classification is based on the teacher's support of students' basic psychological needs for autonomy and competence in different types of interactions, and these two needs are key conditions for intrinsic motivation and well-being. This approach has received robust empirical support and is widely applied in educational practice (Guay, 2022; Reeve, Cheon, 2021).

With an autonomy-supportive style, the teacher strives to understand students' interests and preferences to support their engagement in the learning process. They use inviting language ("let's try it this way") and avoid controlling statements (e.g., "you should /must listen to me carefully and do what I said"), offer opportunities for meaningful choice and decision-making, explain the rationale behind their requirements, and acknowledge negative feelings that arise during learning process. These behaviors contribute to satisfying the basic psychological need for autonomy, i.e., the desire to be the agent of one's own actions (Reeve, Cheon, 2021), which leads not only to higher quality motivation but also to student well-being (Vite, Patall, Chen, 2024). In Russian education, the autonomy-supportive style has active proponents: it is described as a teaching style that supports a child's independence, initiative, and self-sufficiency (Tsukerman, Obukhova, 2024).

With a pronounced controlling style, students lose their sense of agency and ownership of the learning process, as the teacher actively pressures and controls them, forcing them to act and think in a single, "right/ correct" way, disregarding the child's opinion. Control manifests both at the behavioral level (demands for obedience using rewards, grades, and punishments) and at the level of feelings and personality (psychological control), using manipulation, threats, criticism, and appeals to shame. International research shows that, overall, teachers believe the autonomy-supportive style is more effective than the controlling style and tend to consider their own teaching style as more autonomy-supportive than controlling; however, they also believe the latter is more "normal" and easier to implement, which largely explains its high prevalence among teachers in various countries worldwide (Reeve et al., 2014).

Key features of the structuring style include setting clear expectations for desired behavior and outcomes, providing clear explanations on how to achieve them, offering constructive feedback during and after activities, and presenting clear assessment criteria (Patall et al., 2023). This style supports the need for competence (the desire to feel effective and capable), which, like the need for autonomy, is a source of intrinsic motivation (Ryan, Deci, 2017).

Teachers with a chaotic-permissive style demonstrate contradictory, vague, and inconsistent demands, without providing necessary feedback and support, often assuming the role of an observer. Thereby, they prevent students from understanding what needs to be done, how to develop their competence, and how to maintain confidence in their abilities, resulting in students' frustrated need for competence.

Personal and motivational factors of teachers' interaction styles. Previous research indicates that teachers do not randomly choose and use a particular interaction style. Specifically, it has been shown that the autonomy-supportive style is associated with openness to experience and agreeableness, while the controlling style is linked to authoritarianism (Reeve, Jang, Jang, 2018). More personally mature teachers, with higher levels of responsibility, resilience, and developed systemic reflection, tend to use more constructive interaction styles (autonomy-supportive and structuring), whereas teachers with lower levels of these traits tend to use controlling and chaotic styles (Gordeeva, Sychev, 2024).

A meta-analysis has shown that teachers' autonomy-supportive style correlates with higher autonomous motivation for teaching and less pronounced controlled motivation, i.e., they enjoy the process of teaching children and interacting with them, feeling a sense of vocation (Slemp, Field, Cho, 2020). Considering all four styles, it has been shown that autonomy-supportive and structuring interaction styles are associated with teachers' autonomous motivation, while chaotic and controlling styles are associated with controlled motivation (Aelterman et al., 2019).

Consequences of interaction styles are of the greatest interest. It has been shown that students who perceive their teachers as practicing autonomy-supportive and structuring styles have significantly higher autonomous motivation (for the subject), academic self-regulation, deeper learning strategies, planning, monitoring, and perseverance (Aelterman et al., 2019). They generally rate their teacher and teacher’s communication style more highly, are willing to recommend them to others, and continue learning in their class the following year. Conversely, students who perceive their teachers as prone to controlling and/or chaotic styles had more pronounced controlled academic motivation and amotivation, were unwilling to recommend them, and did not want to continue learning with them (Aelterman et al., 2019).

A longitudinal study showed that the perceived teacher interaction style at the beginning of the school year predicted the dynamics of the quality of adolescents' (grades 7-8) academic motivation at the end of the year. By the end of the year, there was a significant decrease in the perceived motivating style (autonomy-supportive and structuring styles), as well as in autonomous motivation and satisfaction of basic psychological needs, alongside an increase in the chaotic style with a corresponding increase in the frustration of basic needs, controlled motivation, and amotivation. The results of multilevel growth curve analysis confirmed that the teacher's motivating interaction style predicts growth in students' autonomous motivation, while the demotivating style (control + chaos) predicts students' controlled motivation and amotivation, while these associations are mediated by the satisfaction/ frustration of basic psychological needs (Cohen et al., 2023).

These results are of significant interest, as research consistently shows that students' academic achievements are reliably associated with high autonomous and low controlled motivation (Howard et al., 2021). However, this problem has not been studied comprehensively. Two previous studies showed that academic motivation depends on teacher's interaction style with the class, but did not simultaneously demonstrate how different styles are related to academic achievement and student perseverance. Furthermore, in the study by Cohen et al. (2023), autonomy support and structure, on one hand, and control and chaos, on the other, were considered as a single variable. The aim of the current study is to determine the independent contribution of these styles to intrinsic motivation, homework time, and academic performance in a sample of Russian school students.

Hypothesis. In accordance with Self-Determination Theory and previous research, we hypothesized that the teacher's autonomy-supportive and structuring styles would be positively related to students' academic achievement in the subject taught by that teacher, and intrinsic motivation would mediate this relationship. On the other hand, controlling and chaotic styles would be directly or indirectly (through intrinsic motivation) negatively related to academic achievement.

In this study, the analysis of interaction style and motivation was conducted in the context of mathematics, as one of the two key subjects studied in schools and included in final assessments in Russia (OGE, EGE) and international assessments of student competency (PISA).

Materials and methods

The sample consisted of eighth-grade students (N = 1731, 55% girls, 43% boys, 2% did not specify gender). The average age was 13,89 years (SD = 0,41). Adolescents from 78 Russian schools participated in the online survey, which was anonymous.

The "Situations in School" questionnaire (Aelterman et al., 2019; Gordeeva, Sychev, 2021), designed for teacher self-assessment of their interaction style, was used. However, in this study, the questionnaire was modified (as in one of the studies by N. Aelterman and colleagues (Aelterman et al., 2019)) so that the interaction style was assessed by the students. For example, item No. 1 "You communicate your expectations and norms of behavior for successful interaction" was changed to "The teacher communicates her(his) expectations and norms of behavior in the class to us", etc. The questionnaire assesses four main styles: Autonomy Support, Structure, Control, and Chaos. This version of the instrument showed high internal consistency coefficients (see Cronbach's α values for all scales in the table). The assessment of the four-factor model showed satisfactory fit to the data: χ² = 5345,23; df = 1074; p < 0,001; SRMR = 0,084; RMSEA = 0,048; 90% CI for RMSEA: 0,047–0,049; PCLOSE = 0,993; N = 1721. Incremental fit indices (CFI, TLI) were not used because they are uninformative when the RMSEA of the baseline model is less than 0,158 (Kenny, 2020): in our case, it was 0,099.

To assess intrinsic motivation for learning mathematics, a scale of five items with five response options, based on the Academic Motivation Scale for school students (Gordeeva et al., 2017), was used. It includes main stem “I learn math because…” and 5 statements reflecting two main types of intrinsic motivation: cognitive (3 items, e.g., "I enjoy learning mathematics, it's interesting") and self-development (2 items, e.g., "I enjoy becoming more competent and knowledgeable in mathematics"). A one-factor model with a covariance between the items measuring self-development motivation showed satisfactory fit to the data: χ² = 37,99; df = 4; p < 0,001; CFI = 0,999; TLI = 0,998; SRMR = 0,004; RMSEA = 0,071; 90% CI for RMSEA: 0,051–0,092; PCLOSE = 0,042; N = 1709.

Homework time was assessed with the question "How much time per day do you usually spend on homework?" with six response options: "30 minutes", "1 hour", "1,5 hours", "2 hours", "3 hours", "more than 3 hours" coded with numbers from 1 to 6, respectively. Academic performance was assessed using final grades in algebra and geometry, reported by the children in response to the question: "What were your grades in algebra and geometry last quarter?".

Data analysis using descriptive statistics and correlations was performed in the R environment. Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling were conducted in Mplus 8 using the weighted least squares method with a polychoric correlation matrix (WLSMV). The statistical significance of mediated effects was assessed in Mplus using bootstrap analysis (5000 samples). The proportion of respondents with missing data did not exceed 5%; pairwise deletion of missing cases was used during correlation analysis and structural modeling.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the measured variables are presented in the table. As expected, intrinsic motivation for learning mathematics showed moderate positive correlations with autonomy-supportive and structuring styles and weak negative correlations with controlling and chaotic styles. At the same time, academic performance showed no significant correlation with the controlling style, while correlations with other styles were similar but smaller in magnitude. Homework time was weakly and positively correlated with intrinsic motivation, academic performance, and the controlling style, and negatively correlated with the chaotic style.

Table

Correlations of teaching styles with intrinsic motivation,

homework time, and math performance

|

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

1. Autonomy support |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Structure |

0,73*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Control |

0,04 |

0,19*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Chaos |

0 |

–0,26*** |

0,31*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

5. Intrinsic motivation to study Math |

0,38*** |

0,41*** |

–0,08*** |

–0,22*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

6. Homework time |

–0,04 |

0,03 |

0,06* |

–0,11*** |

0,11*** |

— |

|

|

|

7. Academic performance in Algebra |

0,09*** |

0,15*** |

–0,02 |

–0,15*** |

0,37*** |

0,17*** |

— |

|

|

8. Academic performance in Geometry |

0,06** |

0,13*** |

0 |

–0,13*** |

0,33*** |

0,15*** |

0,79*** |

— |

|

9. Gender (0 – F, 1 – M) |

0,16*** |

0,03 |

–0,07** |

0,08** |

0,12*** |

–0,24*** |

–0,05 |

–0,04 |

|

Mean |

2,84 |

3,46 |

3,31 |

2,45 |

3,35 |

3,53 |

3,82 |

3,86 |

|

Standard Deviation |

0,85 |

0,74 |

0,65 |

0,76 |

1,13 |

1,52 |

0,72 |

0,73 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0,89 |

0,85 |

0,77 |

0,84 |

0,95 |

— |

— |

— |

Notes. Statistical significance: * – p < 0,05; ** – p < 0,01; *** – p < 0,001. Variable numbers in column headings correspond to row numbers.

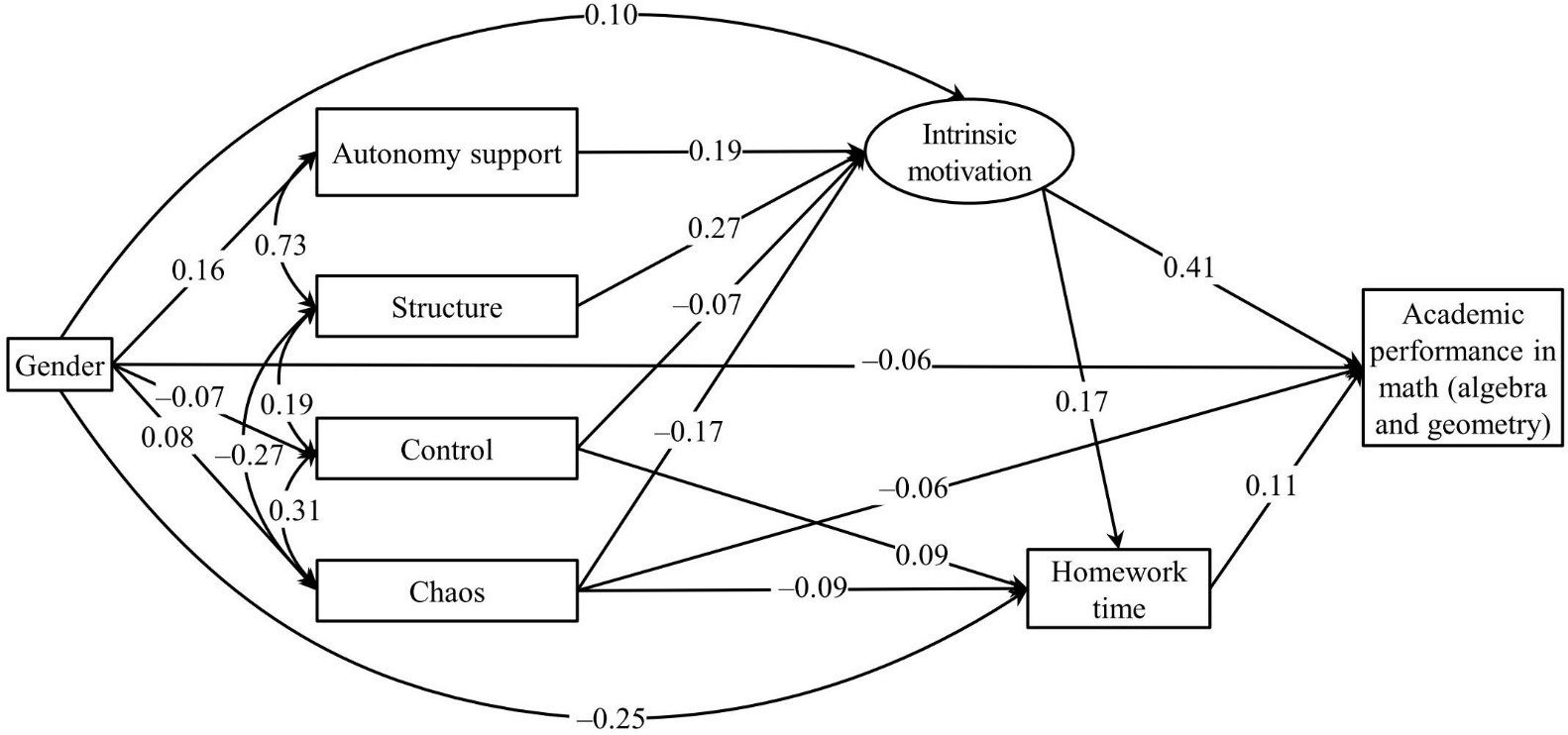

To analyze the direct and indirect effects of teaching styles on academic performance, controlling for gender, a corresponding structural model was constructed. The final dependent variable was the average grade in algebra and geometry. Homework time, intrinsic motivation, and teaching styles were added to the model as its predictors. The factor of intrinsic motivation was formed from five items with one covariance between the items measuring self-development motivation and this factor was considered dependent on teaching styles. Homework time was considered dependent on teaching styles and intrinsic motivation. The model also included a coded "gender" variable with all possible effects on all other variables and factors. Covariances between adjacent teaching styles were allowed. After preliminary model evaluation considering modification indices, a covariance between the chaotic and structuring teaching styles was also added, which is justified by theoretical notions of their opposite manifestations and consistent with previous research results (Gordeeva, Sychev, 2021; Aelterman et al., 2019). The model constructed in this way showed a good fit to the data (see figure): χ² = 163,08; df = 34; p < 0,001; CFI = 0,997; TLI = 0,994; SRMR = 0,018; RMSEA = 0,047; 90% CI for RMSEA: 0,040–0,055; PCLOSE = 0,712; N = 1693.

The model indicates that intrinsic motivation shows the strongest relationship with mathematics performance. Homework time also makes a smaller, but statistically significant, positive contribution to performance; the contribution of the chaotic style is negative and weak.

A direct weak association with gender indicates a tendency towards slightly lower performance among boys. However, boys show more interest in mathematics and a greater desire to improve in it than girls, but they spend less time on homework, which in turn makes a statistically significant contribution to Math grades. The total mediated effect of gender on Math performance is very weak (0,002; p ≤ 0,05) and opposite in direction to the direct effect, so pairwise correlations between gender and achievement show no statistical significance (see table).

Analysis of the mediated effects of interaction styles on Math achievement showed that the effects of the autonomy-supportive (0,08; p ≤ 0,01), structuring (0,11; p ≤ 0,001), and chaotic (–0,003; p ≤ 0,05) styles are statistically significant. The controlling style showed no statistically significant effects on performance.

Discussion

Using a large sample of Russian school students, the proposed hypotheses were confirmed, showing that the perceived teacher's interaction style is a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation, perseverance, and academic achievement. In the context of motivation for learning mathematics, it was shown that autonomy-supportive and structuring interaction styles are indirectly related to students' academic achievement through intrinsic motivation. The teacher's controlling and chaotic interaction styles are negatively related to intrinsic motivation, and the chaotic style is negatively related to academic achievement. The obtained data align well with previous findings on the significance of teacher interaction styles for student motivation (Aelterman et al., 2019; Cohen et al., 2023) but provide a broader and more systemic picture of the effects of these styles on academic success and homework time as an indicator of perseverance.

In our study it was shown that autonomy supportive and structuring styles are closely related which supports previous research (Cohen et al., 2023), and which may favor considering a unified "supportive" interaction style in the future. Conversely, controlling and chaotic styles represent sufficiently independent types, arguing against merging them into a single demotivating style variable, as was done in the study by Cohen et al. (2023). It was shown that the effects of Control and Chaos styles on intrinsic motivation, homework time, and performance differ substantially. Interestingly, the logic of distinguishing three interaction styles also aligns well with the three leadership styles identified by K. Lewin in the early 20th century and modern classifications of leadership styles within SDT (Huyghebaert-Zouaghi et al., 2023).

Regarding gender differences, the data from previous research on boys' greater interest in mathematics (Rodríguez et al., 2020) were confirmed in our study on Russian children. Nevertheless, despite their more pronounced intrinsic motivation for learning mathematics, boys do not show higher academic performance, and this phenomenon may be explained by their lower perseverance, which was measured as the time spent on homework.

Limitations and future perspectives

The main limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for definitive causal conclusions about the role of interaction style in adolescents' motivation and success.

A prospect for future research is to analyze the influence and effects of teachers' teaching styles on other indicators of student academic motivation, such as goal setting and long-term perseverance, as well as on their school well-being. Another prospect involves the trainings development, including video materials, to teach Russian current and future teachers motivating teaching styles.

Practical implications

The study's results have clear practical significance, indicating the importance of training teachers in motivating teaching styles, i.e., supporting autonomy, providing structure, and supporting children’s competence as well as concrete strategies and behaviors that motivate their students. While the idea of structure and competence support is somewhat present in the discourse of Russian teachers (systematicity, consistency, praise), the idea of autonomy support is relatively new. Primarily, it includes offering a student opportunities for making own decisions (choice of tasks, solution strategies, level of difficulty, content, place to seat, etc.), explaining the rationale for requirements, showing respect and attention to the student's point of view, avoiding controlling language and threats related to grades and tests (Wang et al., 2024).

Conclusions

- The results indicate that the perceived teacher's interaction style is a significant factor determining students' intrinsic motivation, persistence, and academic achievement.

- Using a sample of Russian middle-school students, it was shown that perceived motivating (Math) teacher interaction styles (autonomy-supportive and structuring) are positively related to Russian students’ academic achievement, and intrinsic motivation is a mediator of this relationship. Consequently, teachers should be specifically trained in such strategies that support children's desire to learn and do homework.

- Demotivating teacher interaction styles (controlling and especially chaotic) negatively impact intrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Therefore, teachers should refrain from such practices.