Introduction: Contemporary Contexts of Childhood

One of the fundamental perspectives on childhood within the cultural-historical approach is shaped by the “adult-child” relationship. This perspective defines the debate on the interplay between play and learning, a topic actively explored in contemporary research [26; 19, 20]. At its core, this framework raises the issue of childhood subjectivity. The concept of subjectivity encompasses two key characteristics: self-causation and lived experience [PetrovskyA. Sub``ektnost` Ya, 2021]. In other words, subjectivity highlights, on the one hand, that human activity is inherently proactive rather than reactive, and on the other hand, that this internal activity is experienced and felt by the individual. The effort to recognize children as active subjects of their own childhood is reflected in several research directions: incorporating children’s perspectives into childhood studies [Harcourt, 2011], expanding the use of narrative methodologies [Hakkarainen P.,Laitinen, 2017], and exploring ways to integrate play-based methods into children’s learning [Fleer, 2022; Khakkarainen, 2020], among others.

The “adult-child” context aligns with the “cultural-natural” context. The gap in mastering cultural forms between adults and children serves as the foundation for the emergence of a distinct period in human life, defined as childhood [El'konin, 1978, p. 63]. E.V. Ilyenkov described culture as a governing force that stands in opposition to the individual and regulates their behavior: “This power of the social whole over the individual manifests itself directly in the form of the state, the political system of society, a system of moral, ethical, and legal restrictions, norms of social behavior, as well as aesthetic, logical, and other normative criteria” [Il'enkov, 2006, p. 19]. From this perspective, culture and culturally mediated behavior represent a more advanced form of development compared to natural behavior. Limited mastery of cultural forms restricts a child’s ability to express subjectivity. According to L.S. Vygotsky, it is the acquisition of culture that transforms a child’s behavior from natural to cultural, enabling them to become an active subject of their own development.

The acquisition of culture takes place within society, which is defined as the system of norms and rules for interacting with artifacts. The fundamental unit of society is the situation, which comprises both objective and subjective aspects [Veraksa, 2023]. The objective aspect reflects observable and latent characteristics, such as prescriptions, requirements, and rules. The subjective aspect encompasses the individual’s attitude within the situation, including values, goals, and emotional experiences [Wan Urs, 2021; Veraksa, 2024a]. Within a given situation, an individual engages in activity, thereby becoming an active subject of their own development. Consequently, the relationship between “situation and society” establishes a third contextual framework of childhood, which pertains to the roles of children and adults in social interactions [Veraksa, 2024a].

Types of Situations and the Child’s Position

We identify several types of situations, each of which characterizes the child’s position with varying degrees of subjectivity. A preschool-aged child can act within a normative situation, an imaginary (or pretend) situation, and a creative situation. In a normative situation, the child interacts with a cultural artifact that dictates a specific mode of action. The cultural artifact constitutes the external aspect of the normative situation, while the prescribed actions associated with it form the internal or implicit aspect. The key feature of a normative situation is that, among the many possible ways of interacting with a cultural artifact, society establishes specific methods of engagement developed through historical evolution. These methods are not self-evident and cannot be directly inferred from the artifact itself based on the child’s immediate interaction with it. As a result, mastering actions with cultural artifacts is impossible without adult guidance. According to the cultural-historical paradigm, this process of mastery constitutes learning, which is organized by an adult and takes place within the child’s zone of proximal development. In a normative situation, the child assumes the role of a learner, while the adult occupies the role of a teacher. A crucial aspect of mastering a cultural artifact is the use of speech as a form of social interaction aimed at acquiring meanings. The role of speech is determined by the general genetic law of cultural development, formulated by L.S. Vygotsky: “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears on the stage twice, on two planes — first on the social, then on the psychological; first between people, as an interpsychic category, and then within the child, as an intrapsychic category” (Vygotsky, p. 145).The social plane of this process involves the use of speech in communication, serving as a tool for the transmission and internalization of cultural meanings.

An imaginary (or pretend) situation arises in play. This type of situation is characterized by the role that the child voluntarily assumes. It is important to note that accepting a role comes with rules that the child must follow in shaping their behavior. According to Vygotsky, it is not possible for a child to act outside the established rules within an imaginary situation (Vygotsky, 1933/1967). Play, as described by L.S. Vygotsky, has a profound impact on child development. The play space, defined by the imaginary situation, differs from the cultural space, which consists of normative situations built around cultural artifacts. While the cultural space is primarily oriented toward mastering the operational structure of actions, which is linked to a system of meanings, the play space focuses on the semantic dimension of cultural artifacts. Play creates a shared space of meanings among participants, within which play actions are carried out to construct relationships with cultural artifacts. A.N. Leontiev, analyzing a child’s play with a stick (Leontiev, p. 479–480), demonstrated that the play action reproduces the cultural action of an adult in terms of its goal. However, the operations used by the child in play do not correspond to those employed by an adult in real-life activity. A play action is thus characterized by partial alignment with the real action of an adult. This suggests that, due to the complexity of mastering the operational aspect of adult actions, the child first internalizes the meaning behind the action. However, this process of meaning-making occurs largely independently, with limited adult intervention. In this study, we refer to the child’s position within an imaginary situation as the position of a subject, emphasizing their active role in meaning construction during play.

We identify another category of situations — creative situations — aimed at generating something new. Their primary characteristic is the realization of an individual idea and its expression through the creation of a unique product. In this case, the novelty of the product serves as a medium for conveying the child’s individuality. Within the framework of creative situations, project-based activities unfold. The distinctive feature of project implementation is that children often encounter certain difficulties due to their still-developing executive skills. Therefore, in project-based activities, children receive support in carrying out their ideas. The primary role of the adult is to listen to the “voice of the child” and assist in defining and implementing their concept. It is essential for the child to act as the author of the created product and present it to their immediate environment, receiving positive feedback. The degree of authorship in completing the project and the overall productivity of the activity determine the developmental potential of project-based activities and creative situations.

To sum up, in a normative situation, the child acquires cultural meanings through the learning process, assuming the role of a student. In an imaginary situation, the child internalizes cultural meanings by taking on the role of a subject in play. In a creative situation, the child generates new meanings, realizing them in a socially significant product, thereby assuming the role of an author.

Current Study

The analysis of contemporary childhood contexts conducted within the framework of cultural-historical approach has demonstrated that children express their activity in three types of situations: normative, imaginary, and creative. These situations allow preschoolers to assume different roles when interacting with other participants: the role of a student, a subject, and an author. It can be expected that their impact on the development of children’s consciousness will vary depending on the role assumed.

Thus, this study aims to test the hypothesis regarding the dynamics of coherent speech development based on the role the child takes in a given situation. We propose that in the role of an author — where the highest level of agency is achieved through the child’s initiative and its realization — speech development will be most pronounced. This assumption is based on the importance of considering children’s perspectives to enhance educational effectiveness [Alasuutari, 2014; Sargeant], the necessity of activating students’ internal processes for learning and development, such as problem-setting in activities [Leont'ev, 1997], and existing data on the characteristics of speech development in modern preschoolers [Bezrukikh, 2021; Khotinets, 2022]. Study Design

Sample

The study, conducted during the 2023—2024 academic year, involved 125 preschool children aged 5–6 years (M = 70 months, SD = 3,6, 50,4% male). All participants attended public kindergartens in Moscow, located in districts with comparable infrastructure levels. Written consent for participation and video recording was obtained from the parents of all children involved in the study. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at Lomonosov Moscow State University.

During the diagnostic and experimental sessions, certain participants were excluded from the study based on the following criteria: (1) children who attended fewer than half of the sessions (N = 9); (2) children who did not participate in the post-test (N = 29) due to illness or absence from kindergarten on the testing days. As a result, the final sample for analysis included 87 preschoolers (47 boys, 54.6%).

Procedure

A blind randomized controlled experiment was conducted, consisting of three stages. In the first stage, a group of diagnosticians performed individual assessments of children’s speech development. The transcription of narrative audio recordings and their evaluation were carried out by Expert-1, who was unaware of the research purpose and did not participate in either the diagnostics or the conducting of sessions. In the second stage, four experimental groups and one control group were formed: “Play World” (GW), “Free Play” (FP), “Research Project” (RP), “Creative Project” (CP), and the control group (CG). During the pre-test, there were no differences between the groups across all diagnostic measures (Kruskal-Wallis, p > 0.05). The gender ratio of boys and girls was equal across all conditions. Each group participated in 22 sessions lasting 20—30 minutes in subgroups of 10—12 children. The sessions were held twice a week. The sessions were conducted by specially trained psychologists who did not conduct the diagnostics of the children. The psychologists were informed that the sessions were being held for the purpose of testing the programs. Each psychologist led sessions with two subgroups: GW and FP, or RP and CP. Thus, two psychologists conducted sessions in each condition, which allowed for controlling the influence of the pedagogue’s personality on the study results. The fourth, ninth, and eighteenth sessions in all groups were recorded on video using a smartphone for monitoring the implementation of the sessions and for qualitatively assessing changes in children’s behavior and speech manifestations. The recordings were then assessed by Expert-2, who was unaware of the research purpose and did not participate in the diagnostics or the sessions. Expert-2 evaluated the session recordings using tools for categorized observation, including the “Game Matrix” and its analogue for project activities [Veraksa, 2022a]. The observation matrices represent an observation map that includes behavioral, speech, and emotional manifestations of the children. The matrices allow for recording the frequency of manifestations for each category. The matrices included the following categories: impulsive actions, field actions, disengagement from the group context, typical actions within the activity, original actions within the activity, group emotionally charged actions, regulation of other children’s behavior, metacognitive and evaluative statements, typical activity-related statements, such as role-play statements in games, answers to questions in project activities, participation in discussions with other children.

The sessions were completed simultaneously across all groups. In the third stage, a post-test was conducted, similar to the initial diagnostic test, to assess the level of coherent speech. The post-test was conducted by the same group of diagnosticians as the pre-test, with the condition that diagnosticians could not test the same children as in the pre-test.

Measurements

To assess speech development in preschoolers, the method of extracting and evaluating coherent speech (narratives) “MAIN: Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives” [Gagarina, 2019] was used, which allows for assessing both the macrostructure and microstructure of children’s narratives. This method was developed and validated on a Russian sample for children aged 3 to 10 years [Akhutina, 2024; Gagarina, 2019], and has also been adapted for more than 20 languages [Gagarina, 2020], being widely used both in Russia and abroad. Additionally, when evaluating the macrostructure of the narrative, criteria developed by T.V. Akhutina [Akhutina, 2019] were also taken into account to assess the semantic completeness and adequacy of speech, supplementing the MAIN method [Akhutina, 2024]. The child was presented with equivalent picture series “Nest” on the pre-test and “Kids” on the post-test to compensate for the learning and memory effects, in accordance with the developers’ recommendations [Hakkarainen P.,Laitinen, 2017]. Both series consist of a sequence of 6 pictures, which are combined into 3 episodes. For the procedure, the series were printed and folded into a “fold-out book.” The child was allowed to look at the book, and the following instruction was given: “Now I will show you some comics. Do you like comics? Look. What happened here? Tell me so it becomes a real story. Tell as much as you can.” The child’s narrative was recorded on a voice recorder. After transcription, the number of words in the child’s story, the speech rate (the ratio of the number of words to the time taken to tell the story), and the macro — and microstructure of the narrative were assessed. The macrostructure of the story (max. 10 points) includes 2 subscales, each rated from 1 to 10 points, and then their arithmetic mean is calculated: story programming (semantic completeness, internal coherence, and adherence to the narrative structure “goal — action — result”) and semantic adequacy (the correspondence of the story to the presented pictures, understanding of cause-and-effect relationships). The microstructure (max. 10 points) also includes 2 subscales, each rated from 1 to 10 points, and then their arithmetic mean is calculated: lexical presentation of the story (correctness of word usage, morphological variety) and grammatical-syntactic presentation of the story (grammatical and syntactic errors, grammatical-syntactic variety).

Intervention

In the PW group, a educational practice “Play Worlds” was used to organize pretend play based on a fairy tale plot, with an adult acting as a play partner [Fleer, 2022]. Participants were offered abridged versions of the fairy tales “Pinocchio” and “The Wizard of Oz” as plot foundations. The experimenter read the stories to the children, after which a discussion and role distribution were organized, with the experimenter taking on one of the roles. Using a “portal,” participants moved into the play world, selected appropriate attributes for their roles, and began playing. Strict adherence to the original storyline was not required. The child’s position in the PW group was determined by their understanding of the plot and role, followed by adherence to necessary rules. This effectively represented a subjective (reflexive) position.

Within the FP group, experimenters assisted children in initiating pretend play, for example, by organizing a discussion on selecting the theme and roles, but then did not interfere in the game. The free play took place in an environment enriched with non-play materials such as sticks, cones, boxes, leaves, and other objects. These non-play materials were used to expand the possibilities for implementing various play themes and to encourage the use of substitute objects in role-playing games. In the FP group, adults were minimally involved in organizing the play and did not immerse themselves in the imaginary situation.

In the RP group, two projects were created — one on space and the other on electricity. During the sessions, experimenters introduced a problem situation related to the theme of space or electricity, facilitated discussions, and helped define a specific research question formulated by the children, such as: “How does the light in the lamp appear in our kindergarten?” The experimenters then assisted the children in developing a plan for finding answers, directly gathering and documenting information, designing a project product, and presenting their findings to peers and adults. The experimenters acted as assistants, while the main initiative came from the children, fostering a creative environment, a sense of authorship, and productive activity.

The CP group was also characterized by an authorship position and productive activity. The children created a model of space and an original theatrical performance. The sessions included problem situations and discussions that encouraged children to develop a creative product. To determine the project’s goal and final product, children proposed their ideas, craft sketches, and play scripts, after which one of the suggested options was selected through voting. Participants then moved on to planning and directly implementing the project. In this case, experimenters also acted as assistants, following the children’s initiative and helping with the technical aspects of the work. Upon completion, the group presented their projects in kindergarten.

Data Analysis

The analysis consisted of two stages: a preliminary stage and an analysis of differences in the influence of the experimental groups. Initially, the data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances across groups using Levene’s test. Normal data distribution and equal variances were considered prerequisites for conducting an analysis of variance (ANOVA). A multifactor ANOVA was performed to assess differences between children who dropped out of the experiment and those who remained in it. The independent variables included inclusion/exclusion in the final sample and assignment to an experimental group. ANOVA was conducted on the final sample to check for any differences between the study groups at the preliminary testing stage. The Chi-square test was used to assess gender distribution across the groups. During the main stage of data analysis, a repeated measures multifactor ANOVA was conducted for normally distributed data, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to non-normally distributed data. The independent variables in the ANOVA included gender and assignment to an experimental group. Throughout the analysis, statistical significance was set at p = 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis

At the pre-test, including all children who participated in the study (n = 105), the data on speech rate (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 0.977, p = 0.09; Levene’s test, F(4, 91) = 0.336, p = 0.661), macrostructure (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 0.975, p = 0.068; Levene’s test, F(4, 91) = 1.22, p = 0.309), and microstructure (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 0.981, p = 0.186; Levene’s test, F(4, 91) = 0.798, p = 0.53) of the narrative were normally distributed and had equal variances across groups. However, the word count data were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 0.833, p < 0.001). A multifactor ANOVA was used to assess differences between children who dropped out of the experiment and those who remained in the final sample. The independent variables were “inclusion/exclusion in the final sample” and assignment to an experimental group. The analysis showed no significant differences in speech rate, macrostructure, or microstructure of the narrative (p > 0.05). For the macrostructure of the narrative, a significant interaction effect was found (ANOVA, F(4, 86) = 3.71, p = 0.008), but post-hoc tests did not reveal pairwise differences between groups (Bonferroni-adjusted p > 0.05). Children who dropped out of the study and those who remained in the final sample also did not differ in word count in their narratives at the pre-test stage (Kruskal–Wallis test, χ²(1) = 0.00799, p = 0.929).

At the pre-test and post-test, considering only participants included in the final sample, the normality of data distribution and equality of variances for speech rate, macrostructure, and microstructure (Tables 1 and 2) remained consistent across groups. The distribution of word count in the composed narrative remained non-normal (Tables 1 and 2). At the pre-test, no significant differences were found between the groups for any of the assessed indicators (ANOVA, p > 0.05). Data on the quantitative and gender composition of the groups, as well as medians and standard deviations, are presented in Tables 1 and 2. While no significant differences in gender composition between groups were found, a trend-level effect was observed (χ²(4) = 9.07, p = 0.059). Additionally, research indicates significant differences in the development of coherent speech between preschool-age boys and girls [Harcourt, 2011]; therefore, the gender factor was controlled for in the further analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the assessed indicators at the pre-test for the experimental and control groups

|

Indicator |

Study group |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Shapiro— Wilk test |

Levene’s test |

Group differences |

|||||||||

|

Word count |

Play worlds (N =22, 59% male) |

48,8 |

13,5 |

W = 0,819, p < 0,001 |

F(4,59) = 0,361, p = 0,835 |

Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(4) = 4,03, р = 0,402 |

|||||||||

|

Free play (N=25, 52,9% male) |

48,5 |

25,2 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project (N =10, 60% мальчики) |

42,4 |

29,4 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project (N = 10, 40% male) |

47 |

19,4 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group (N = 20, 42% male) |

43,6 |

12,9 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Speech rate |

Play worlds |

0,922 |

0,292 |

W = 0,976, p = 0,249 |

F(4,59) = 1,05, p = 0,387 |

ANOVA, F(4,59) = 2,24, p = 0,075 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

0,875 |

0,281 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

0,805 |

0,390 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

1,09 |

0,352 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

0,687 |

0,173 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Narrative macrostructure |

Play worlds |

5,32 |

1,2 |

W = 0,968, p = 0,092 |

F(4,59) = 1,35, p = 0,263 |

ANOVA, F(4,59) = 1,82, p = 0,138 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

4,65 |

1,17 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

4,2 |

1,14 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

5,44 |

1,81 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

5,11 |

1,27 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Narrative microstructure |

Play worlds |

4,95 |

1,27 |

W =0,969, p = 0,112 |

F(4,59) = 0,293, p = 0,882 |

ANOVA, F(4,59) = 2,17, p = 0,083 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

4,35 |

1,17 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

4,5 |

1,08 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

5,44 |

1,51 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

5,11 |

1,13 |

|

|

|||||||||||

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the assessed indicators at the post-test for the experimental and control groups

|

Indicator |

Study group |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Shapiro– Wilk test |

Levene’s test |

Group differences |

|||||||||

|

Word count |

Play worlds |

51,9 |

15 |

W =0,963, p = 0,034 |

F(4,59) = 2,09, p = 0,092 |

Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(4) = 4,21, р = 0,378 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

52,7 |

16,3 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

43,6 |

21,6 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

63 |

23 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

50,3 |

21,9 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Speech rate |

Play worlds |

0,959 |

0,19 |

W = 0,980, p = 0,305 |

F(4,67) = 0,719, p = 0,582 |

ANOVA, F(4,67) = 2,62, p = 0,042 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

0,920 |

0,205 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

0,869 |

0,284 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

1,16 |

0,196 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

0,912 |

0,262 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Indicator |

Study group |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Shapiro– Wilk test |

Levene’s test |

Group differences |

|||||||||

|

Narrative macrostructure |

Play worlds |

6,09 |

1,07 |

W = 0,989, p = 0,785 |

F(4,67) = 0,264, p = 0,899 |

ANOVA, F(4,67) = 11,2, p < 0,001 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

5,47 |

0,9 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

4,33 |

1,19 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

6,25 |

1,64 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

3,79 |

1,47 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Narrative microstructure |

Play worlds |

6,25 |

1,14 |

W = 0,984, p = 0,468 |

F(4,67) = 2,2, p = 0,079 |

ANOVA, F(4,67) = 6,58, p < 0,001 |

|||||||||

|

Free play |

5,68 |

1,1 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Research project |

4,61 |

1,27 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creative project |

6,25 |

1,38 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Control group |

4,57 |

1,2 |

|

|

|||||||||||

Analysis of differences

Given the unequal group sizes, disproportionate gender distribution, as well as the normal distribution of data and homogeneity of variances across groups, a repeated measures multifactor ANOVA was conducted to compare the effectiveness of play-based and project-based activities in developing coherent speech (speech rate, macrostructure, and microstructure of the narrative). The independent factors included the experimental group and gender. For word count in the narrative, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

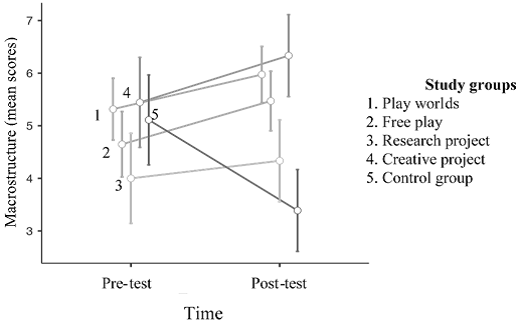

A significant interaction effect between time and the experimental group was found for the macrostructure of the narrative (RM-ANOVA, F(4, 51) = 4.43, p = 0.004, η² = 0.046, see Fig. 1). Post-hoc analysis revealed that, at the post-test stage, children in the PW group scored significantly higher on macrostructure than those in the control group (t = 5.03, Bonferroni-adjusted p < 0.001) and showed a trend-level advantage over children in the RP group (t = 3.42, Bonferroni-adjusted p < 0.049). Children in the FP group scored significantly higher than those in the control group (t = 4.14, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.006). Children in the CP group demonstrated significantly better results in narrative macrostructure than those in the RP group (t = 3.63, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.029) and the control group (t = 4.86, Bonferroni-adjusted p < 0.001).

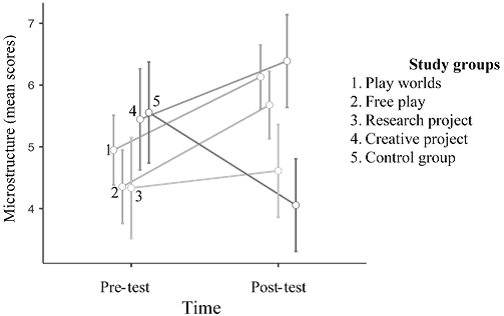

A significant interaction effect between time and the experimental group was also found for the microstructure of the narrative (RM-ANOVA, F(4, 51) = 4.2, p = 0.005, η² = 0.062, see Fig. 2). Children in the PW group (t = 4.26, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.004) and the CP group (t = 3.75, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.02) scored significantly higher on microstructure than children in the control group.

A trend-level difference was found between the groups in the change of scores (differential differences) from pre-test to post-test (Kruskal–Wallis test, χ²(4) = 9.5, p = 0.050, ε² = 0.132). Pairwise comparisons showed that, at the trend level, children in the CP group produced narratives with a higher word count than participants in the RP group (DSCF, W = 3.797, p = 0.056).

No significant differences were found for speech rate. Additionally, no significant differences were observed between boys and girls.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of a child’s position in the educational situation on the development of coherent speech. In the CP group, the greatest number of significant or trend-level positive effects was observed. In this case, the authorial position, productive activity, and social demonstration stimulated the child’s communication with others during explanation, idea selection, discussion, and presentation. The creation of a unique product, i.e., the making of something new [Dorofeeva], expressed the child’s individuality not only in the process of conceiving the product but also in its production. In terms of content, this influence was evident, for example, in the fact that CP participants, Herman and Artem (pseudonyms), became approximately seven times more likely to engage in discussions with peers by the end of the program, compared to the third and fourth meetings, according to video-recording assessments. Furthermore, Herman’s number of self-initiated statements, such as answering questions from the teacher voluntarily rather than at the teacher’s request, increased from 5 to 14 statements, while Artem’s increased from 1 to 5. No such changes were found for children in the PW, FP, and RP groups, highlighting the unique position of the child in the CP group — markedly authorial and productive.

The PW, FP, and CP groups were effective in developing coherent speech at the semantic level of the macrostructure. At the same time, PW and CP had a significant impact on the development of vocabulary and grammar at the microstructure level of the narrative. In the PW and FP groups, preschoolers acted in a pretend situation and took on a subject position. The subjectivity of the position was characterized by two features: 1) the child was aware of the plot and the role they were playing; 2) the child independently determined and performed the corresponding roles in the plot of the action [Yudina, 2022]. However, in the PW group, the adult also became an equal participant in the imaginary situation. Since a rich and developed pretend play requires various skills from the child (e.g., having an understanding of the diversity of the surrounding reality, being familiar with a wide range of characters, being able to create and hold an imaginary situation in their mind, using substitute objects, cooperating with peers, etc.), the adult, as a bearer of cultural experience and knowledge, can enrich the child’s play by providing examples of actions, roles, dialogues, and intonation [Veraksa, 2022; El'konin, 1978]. The adult’s participation in the child’s role play can influence its course, richness, and the children’s expressions, including their speech. Therefore, to some extent, the inclusion of an adult may also impact the development of coherent speech in children [Veresov], which likely explains the greater effectiveness of PW compared to FP, as found in this study. Since play is not productive in the same way as project activity, preschoolers’ position was limited to active involvement in the play, which may explain the greater influence of CP on speech development. It is important to note that the manifestation of macro — and microstructure development reflected differently in actual activity. For example, CP participants Herman and Artem made a significant number of metareflective and evaluative statements about their activities, such as: “You did a beautiful job. You draw beautifully! But mine (about the drawing) is more interesting. No one has ever done anything like this,” “I understood that I can fix it, improve it,” or “Well, that’s not the right way to do it! You need to use another color, remember how we agreed... when... when we were choosing with the coins (about voting for the best model of the product).” On the other hand, during the third and fourth sessions, such statements were absent in these children. Meanwhile, in the PW and FP

groups, the preschoolers Denis, Yaroslav, Petya, and Kolya (pseudonyms) showed a 4—5 times increase in emotional statements and exclamations about the game or their role, for example: “No! I won’t give you the key! You’re bad (with a serious, angry intonation)” or “Hooray! Yes, let’s do it this way! (joyfully and loudly).” The children became more deeply emotionally immersed in the pretend situation, expressing their desires and emotions more openly and freely.

It is important to note that the dynamics in the RP group, based on the speech diagnostics results, did not differ from the control group. The authorial position in RP was limited, as the research question, although reflecting individuality, presented a product that conveyed already known, objective information — strictly speaking, a fragment of the informational space, not individual concepts [Veraksa, 2023a]. Meanwhile, the participants in the CG acted in accordance with the established system of rules within the preschool setting and in normative situations, following the prescribed instructions. It seems that the child’s position in RP does not significantly differ from the typical position of a child in preschool or in CG, where their ideas, though expressed, are constrained by the structure of the lesson plan, the rules convenient for the teacher to maintain discipline, the daily routine of the group, etc.

Thus, it was shown that the more subject-oriented the child’s position, the more pronounced the development of coherent speech, which supports the overall hypothesis of the study. The results of the two groups, PW and FP, were similar in the average indicators of the dynamics of word count, as well as the development of the macro — and microstructure of the children’s narratives. The results of the children in the RP and CP groups differ due to the differences in the positions they occupied. The most beneficial situation for the development of coherent speech is a creative one, where the child occupies a full-fledged position as the author of their idea and product, as seen in a creative project. The obtained data align with other studies and theoretical works that highlight the importance of the child’s subject position, as well as taking their initiative and perspective into account in the educational process for development [Alasuutari, 2014; Sargeant].

Conclusion

This study on the relationship between the child’s position in the educational situation and the development of coherent speech was conducted within the framework of the cultural-historical approach. Several contexts that determine the development of coherent speech in preschoolers were identified: “adult — child,” “natural — cultural,” and “situation — society.” The results of the study indicate that there is a dependency between the development of coherent speech and the position occupied by the child in the educational situation. The results showed that children who occupied an authorial position in a creative project demonstrated the development of coherent speech across the most parameters. The imaginary play situation, where the child assumes the position of a subject, also contributes to the development of the meaning level of speech, vocabulary, and grammar, regardless of the extent to which the adult is involved in the play. The least developmental potential is found in the normative situation, where the child occupies the position of a student.